A moment of silence for 2016, the year liberals failed to stop an authoritarian from becoming president. Too often, instead of offering voters progressive solutions for their grievances, the Democratic Party gave us a campaign deeply saturated in superficial celebrity and pop culture. As the party dithered, its supporters grasped for an appropriate response to Trump. They didn’t come up with much; but they did buy a hell of a lot of branded swag. This was the year that many liberals turned to forms of protest that were convenient and often social media–based, but ultimately ineffectual: Drumpf hats, safety pins, and thinkpieces about Harry Potter. They’re each deeply narcissistic gestures that put the individual front and center. To borrow a term from sociologist Charles Tilly, this was an inadequate repertoire of contention.

The year of faux-protest arguably started with Donald Drumpf. John Oliver’s revelation of the Trump family’s ancestral German name was intended to rattle Trump’s followers. Behold the inner thought of the Drumpf superfan: “Haha! Trump supporters are so dumb they don’t understand the hypocrisy!” Some of them are that dumb, but most of them just don’t care. They only would have cared if Trump’s ancestral name was “Rodriguez” or “Ahmed,” not Drumpf. Drumpf is solid and reassuringly German, like a warm Luger in your hands. Oliver fed into xenophobic stereotypes to produce a meme with no political utility. It didn’t succeed in harming Trump’s campaign at all.

Despite its uselessness, Drumpf became briefly, inexplicably popular. People took selfies in special Make Donald Drumpf Again hats. They tweeted smoking hot burns blaring #MakeDonaldDrumpfAgain. There’s even a Chrome extension that replaces “Trump” with “Drumpf.” Yet the only concrete outcome of this protest was that HBO won a ratings boost. Oliver’s segment broke viewing records. It premiered in February; by June, he’d sold 50,000 Make Donald Drumpf Again hats. Jay-Z even wanted one! And is it really a protest if you can’t buy merchandise from HBO?

Alas, #MakeDonaldDrumpfAgain did not sway the election. Trump won the electoral vote and, barring Armageddon, will take office in January. Confronted with the prospect of President Donald Trump, liberals hit the books for inspiration. Just not books about history or politics.

Welcome to the wizarding world of liberal politics! In chronological order, a depressing tale:

- 23 Hilarious and Scary Images That Prove Donald Trump is Voldemort in Disguise (Thought Catalog, March 2015)

- If Democrats Were ‘Harry Potter’ Characters, Hillary Clinton Would be the Wise and Inspirational Dumbledore (Bustle, June 2015)

- This Harry Potter Hat Sorted Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump Into Hogwarts Houses (The Kansas City Star, June 2016)

- How 2016 Presidential Characters Fit Into the Harry Potter World (Daily Kos, August 2016)

- Donald the Dementor: How ‘Harry Potter’ Explains Trump’s Destructive Power (The Huffington Post, August 2016)

- Harry Potter is Helping Readers Make Sense of This Presidential Election (Bustle, November 9, 2016)

- People are Turning to Harry Potter for Comfort After the Election (Buzzfeed, also on November 9, 2016)

This is a small sample because I began to lose the will to live during the process of compiling it. There are more examples: ABC News ran a segment called “Finding the Relationship Between Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump, and Harry Potter,” while The Mary Sue called Clinton “The Hermione of Politics.” And J.K. Rowling eventually contributed to the problem by, as The Daily Dot called it, “destroying Donald Trump in one tweet.”

It all became a bit too much. “The truth is, though, that Potter is, at most, a very basic guide,” an exasperated Corey Atad wrote in Esquire. “It is a book for children, and while adults can gain from those valuable jolts of simple clarity, the simplicity can only take us so far.”

In the minds of well-intentioned Trump opponents, Harry Potter acquired political baggage. It wasn’t enough to enjoy the books or movies; instead, liking them had to signal something good and true about the fan herself. So it became a rudimentary activist gesture. Wands out, and we’ll win the day. This formulation is much too simplistic to address the specifics of Trump’s political appeal, or to inform our resistance to it. In most geek properties, and in Harry Potter especially, danger is filtered through a lens of twee. There’s never any doubt that the hero will win the day, even if a few supporting characters bite the dust in the process. Reality is dirtier. America was never Hogwarts, and few of us have ever been heroes. We’ll be doomed by politics that tell us otherwise.

In the box that contains your Harry Potter wand and your Donald Drumpf hat, make space for your safety pin. Initially introduced in the U.K. post-Brexit, online activists tried to popularize it in the U.S. after Trump’s election. The safety pin allegedly provided anti-racist allies with a way to demonstrate their solidarity to the world. Stick it on your lapel, and marginalized people will immediately know they are safe with you. It’s a bit like an activist ring of power, except that instead of rendering the bearer invisible it accomplishes precisely the opposite effect.

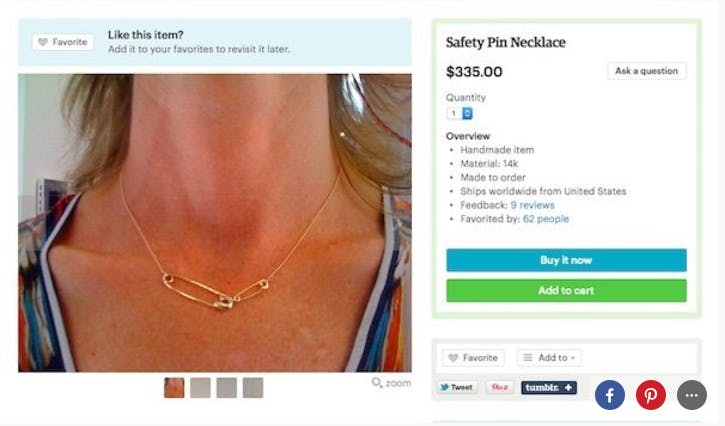

“Let’s call these safety pins what they are: an empty gesture,” Demetria Lucas D’Oyley wrote at the Root. “These pins—not the wearing of them or the pictures posted of folks wearing them—are not about safe spaces. They’re about not wanting to be perceived as a racist.” In practice, the safety pin functioned as hypervisible proof that the wearer is woke. This is perhaps why it was instantly commercialized:

Show your solidarity by wearing beautiful safety pin jewelry: https://t.co/C8OoliQqtN #powerful #statement pic.twitter.com/C9OL7ENXRC

— Livingly (@Livingly) November 30, 2016

Symbols are important, its defenders insisted, and this is true. But a symbol’s power depends entirely on its boosters. There’s no evidence the safety pin has done anything to stem a growing number of racist hate crimes in the land of its birth. There’s no evidence, even anecdotally, that safety-pin wearers in the U.S. or the U.K. have ever intervened to stop a hate crime in progress.

As a political symbol, then, it has always lacked import. Compare it to the red ribbon for AIDS: Activist-artists created it to draw attention to an unfolding epidemic that directly affected their lives. But in each of its iterations, the safety pin has been promoted and deployed by individuals a step removed from the discrimination they intend to fight. Whatever flaws the safety pin possesses as a tactic can largely be traced to its origins.

Instead of protecting vulnerable people, the safety pin has spawned think pieces, agonized blog posts, and allegations that white-supremacists have already co-opted it. It is superficial and ultimately inadequate, not a demonstration of real solidarity.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with drawing inspiration from books, TV shows, or films. Art and comedy unquestionably have subversive power and so can symbols. But they can’t accomplish much outside the context of a comprehensive social movement.

This again is partially a failure of the Democratic Party. For better and frequently for worse, it’s branded itself the progressive alternative to the GOP. But its liberalism is incapable of fashioning a compelling political response to authoritarianism. It defines no contention and makes no demands of anyone with real money or power. It accommodates, and tells its supporters that this is common sense. And it failed, utterly, to introduce anything resembling a coherent contentious politics to its supporters. Call it the safety pin model of politics: It looks nice, but doesn’t benefit anyone it says it wants to help.

In his book Regimes and Repertoires, Tilly defined “contention” as the consequential claims one group makes upon another group or regime, and “repertoire” as the claim-making routines groups use to achieve their objectives. The theatrical metaphor here emphasizes the point that activist social movements tend to draw their tactics from familiar collections of scripts. If a repertoire worked on one type of regime, chances are better than zero it’ll work on a similar type of regime in the future.

It’s not as if would-be Trump protesters lack examples of successful American protest movements. At Standing Rock, indigenous people gathered to demand a specific set of consequences: clean water and respect for their sacred burial grounds. They organized a public, semi-permanent occupation in protest of government overreach. They suffered arrest. Private security and police attacked them and seriously injured some. They endured terrible weather and local harassment. But they persevered. As their resistance became more public, it attracted more participants—and created such a political headache that the Obama administration capitulated.

In North Carolina, Moral Mondays protesters deserve significant credit for helping oust the state’s Republican governor. Then there’s Fight for 15, which successfully pushed for a higher minimum wage in several major metropolitan areas, and Black Lives Matter, which is training a new generation of activists to confront institutional racism and police brutality. Each protest is a collective effort with a clear demand, with marginalized people at the helm. And far from casting America as a shining Hogwarts on a hill, each acknowledges that this country has only ever been good, or fair or free, for a very select number of people. That’s exactly why they worked.

If you’ve never had to contend for anything, you’re unlikely to think of these protest movements, or their historical antecedents, when responding to Trumpism. Harry Potter is more relevant to your daily life than contention. A safety pin, a stupid hat: These seem like truly subversive concepts to you. But cartoon protests only work on cartoon autocrats.