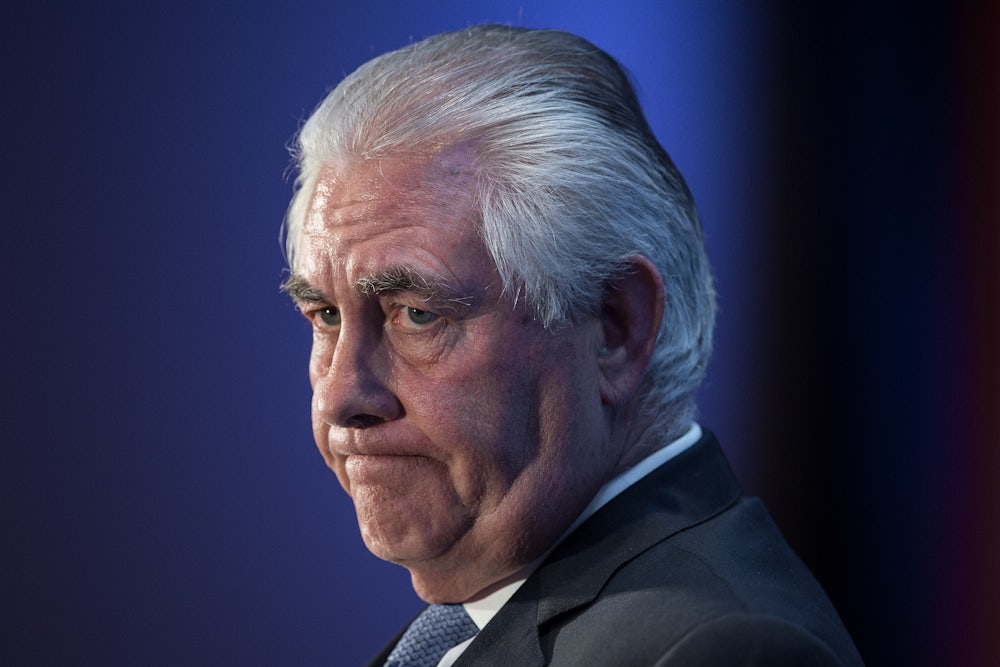

President-elect Donald Trump is taking a huge gamble by nominating Rex Tillerson to be secretary of state. The Exxon Mobil CEO is notorious for making lucrative business deals with Russia, and in 2012 he was awarded the Order of Friendship by President Vladimir Putin. Since American lawmakers of both parties are alarmed by reports from the intelligence community that Putin interfered with the U.S. election with the goal of helping Trump, picking Tillerson for the highest cabinet position is likely to stoke fears—and make for heated confirmation hearings in the Senate.

Indeed, the bipartisan backlash began the moment Tillerson’s name was first floated. Arizona Senator John McCain told Fox News on December 10, “I don’t know what Mr. Tillerson’s relationship with Vladimir Putin was, but I’ll tell you it is a matter of concern to me.” The following day, Florida Senator Marco Rubio tweeted, “Being a ‘friend of Vladimir’ is not an attribute I am hoping for from a #SecretaryOfState.” Many Democrats share these concerns about Tillerson’s Russian ties, and also worry that putting an oil executive in charge of U.S. foreign policy confirms their suspicions about Trump’s plutocratic tendencies. In the words of New Yorker reporter Steven Coll, who has written a book about Exxon’s foreign policy, “As an exercise of public diplomacy, [Tillerson’s nomination] will certainly confirm the assumption of many people around the world that American power is best understood as a raw, neocolonial exercise in securing resources.”

But Tillerson may be preferable to the available alternatives. The other candidates Trump considered for the position—former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, retired General David Petraeus, former U.N. Ambassador John Bolton, and former presidential candidate Mitt Romney—all adhere to some variation of Republican hawkishness.

Giuliani and Bolton, for example, have both been closely aligned with a combative neoconservative foreign policy. As The New York Times noted, Giuliani is “deeply suspicious of Iran and a proponent of aggressive military posture.” Bolton has called for the bombing of Iran and wanted to launch a war against Cuba over non-existent weapons of mass destruction. Petraeus is most famous as the architect of the troops surge in Iraq and as an advocate of counterinsurgency. Romney, meanwhile, was welcomed by many as a possible calming influence on Trump, but on a host of issues he is quite aggressive. Romney opposed the nuclear deal with Iran, referred to Russia in 2012 as “without question our No. 1 geopolitical foe,” and advocated for a military buildup in the Pacific to counter China.

Donald Trump is not someone who needs more belligerent voices in his ear. Already as president-elect he’s escalated tensions with China by breaking with the longstanding diplomatic policy of top American officials not talking to the president of Taiwan. This may have been a ham-fisted attempt on Trump’s part to gain some leverage as he tries to renegotiate trade deals with China, abetted perhaps by advisers who are pushing him to pursue an anti-China policy.

Someone like Trump, so prone to pick fights he doesn’t necessarily understand, needs a calming voice to advise him on foreign policy. Tillerson could be that voice, since his major foreign policy goal is to make business deals. As described by Coll, the foreign policy of Exxon has much in common with diplomatic realism, prizing as it does stability above all else:

Although ExxonMobil has a stated policy of promoting human rights, and has incorporated the advice of human-rights activists in its corporate-security policies, it nonetheless works as a partner to dictators under a version of the Prime Directive on “Star Trek”: It does not interfere in the politics of host countries. The right kinds of dictators can be more predictable and profitable than democracies. ExxonMobil has had more luck making money in Equatorial Guinea, a small, oil-rich West African dictatorship that has been ruled for decades by a single family, than in Alaska, where raucous electoral politics has made it hard for Exxon to nail down stable deal terms. Similarly, ExxonMobil promotes the rule of law around the world—especially that part of the rule of law that favors international investment and makes international contracts enforceable.

This sort of fossil-fuel realpolitik might seem callous, but it is far less likely to lead to wars than either the neoconservative pugnaciousness of Bolton or Trump’s own mercantilist hunger for trade wars. Of all Trump’s candidates for secretary of state, Tillerson seems like the least likely to lead America into armed conflict. He might be too pro-Russia, but that’s a small price to pay for someone who is also likely to be much more willing to sit down and talk with the governments of Iran, Venezuela, or China.

Trump’s government is shaping up to be a team of plutocrats and militarists. The militarists are more scary than the plutocrats because they can unleash real violence in the world. James Mattis, Trump’s nominee for secretary of defense, falsely believes that ISIS is a pawn of Iran. Mike Flynn, Trump’s incoming national security advisor, pushed the equally false theory that Iran was behind the 2012 attack on the U.S. diplomatic compound in Benghazi, Libya. Bolton, whose is being floated as undersecretary of state, is pushing for regime change in Iran. Tillerson, whose main interest seems to be making money from resource extraction, could be our only check on this group of unhinged militarists.

There remains the issue of climate change, since the secretary of state leads climate negotiations for the U.S. Here, too, Tillerson among the best of a bad lot. Exxon has long fostered climate change denial, but he has acknowledged that climate change is real and in 2009 came out in favor of a carbon tax. To be sure, Exxon under Tillerson has vastly underrated the dangers of climate change and been too complacent about adapting to a warmer world, but that is also true of most Republican political actors. Tillerson’s position on climate is deeply flawed, but at least he acknowledges the problem exists, which will put him well ahead of the president he will serve, who tweeted in 2012 that “the concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese in order to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive.”

Finally, Tillerson is not a social conservative like Vice President Mike Pence or other members of the incoming administration. In fact, Tony Perkins of Focus on the Family has attacked Tillerson for his work opening up the Boy Scouts to accept openly gay members and for giving corporate money to Planned Parenthood.

Of course, to say that Tillerson is the best secretary of state we can hope for under Trump is faint praise. Like Trump’s other ultra-rich nominees, the selection of Tillerson points to a government that will be openly plutocratic, promoting the interests of big business above all. That’s a bleak future, but we can take some solace in the fact that Tillerson is more likely to want peace among global powers rather than a diplomatic brawl.