Last spring, while working on a story about the displacement of San Francisco’s LGBT communities, I spoke with a longtime AIDS activist who seemed almost nostalgic for the days when infected gay men dropped dead on Castro Street. “We were doing better when everybody was afraid of us,” he told me, noting that in the 1980s the rest of the city considered the Castro a charnel house and steered clear. Housing prices in the neighborhood were down 25 percent by 1992, he recalled. Nobody wanted to rub shoulders with the plague. “There was something about the intensity of that time,” he said. “The mundane world pales in comparison.”

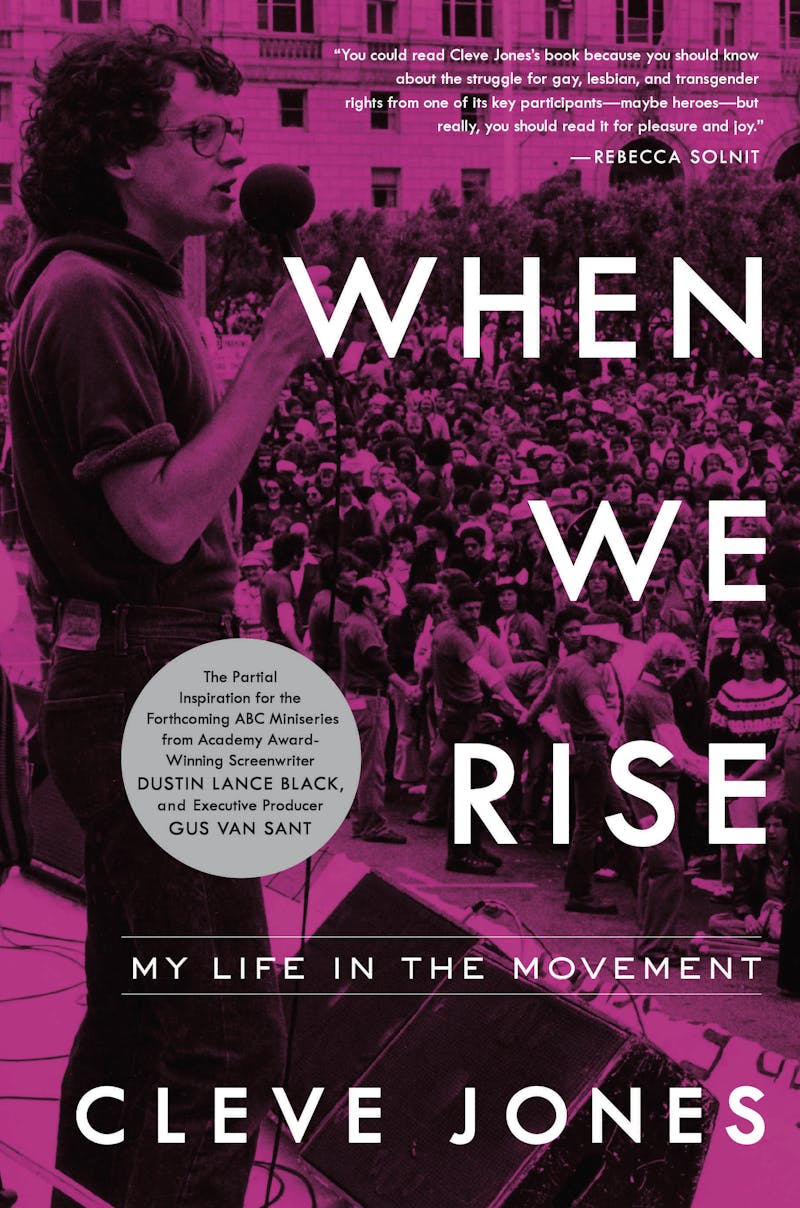

A similar wistful spirit runs through When We Rise: My Life in the Movement, a new memoir by activist Cleve Jones, who created the AIDS Memorial Quilt, co-founded the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, and was a protégé of the iconic gay city supervisor Harvey Milk. (Emile Hirsch portrayed a young, mop-haired Jones in the 2008 biopic Milk; Guy Pearce will star in the ABC mini-series adaptation of When We Rise that will air in 2017). Although Jones doesn’t pine for the plague years—the book’s most wrenching chapters tally the deaths of his many lovers and friends—he does yearn for the compassionate San Francisco where the epidemic ran amok, and for an era when gay liberation reached its apotheosis. As much as Jones’s book is a record of his career on the frontline, it’s also a love letter to the City by the Bay—if you’ve paid attention to San Francisco’s housing market over the past decade, you know that love letter is now a eulogy.

Jones hitchhiked to San Francisco from Arizona in 1973 with $42 to his name. Only 19, he had already picketed alongside the United Farm Workers, distributed petitions for the Equal Rights Amendment, protested the Vietnam War, and campaigned for Senator Eugene McCarthy in the 1968 presidential election. In 1971, while ditching gym class to hole up in his high school library in Phoenix, Jones read a story in Life with the headline “Homosexuals in Revolt,” a report on the burgeoning gay liberation movement that portrayed San Francisco as a new queer mecca. “I am pretty sure that was the exact moment I stopped planning to kill myself,” Jones writes.

In San Francisco he found himself in the middle of that revolution, one that was as much sexual as it was political. In our Grindr era, when arranging a hook-up has the fanfare of ordering takeout, it’s hard to conjure the mix of pride and joyful naïveté that defined gay life in the 70s. Jones recalls cruising Buena Vista Park where a tree house in the branches of a giant eucalyptus doubled as a crash pad and impromptu sex den. (In today’s housing market, that same scenic tree house could surely fetch $3,000 a month.) Then there were the bathhouses. “The only diseases we had to worry about were easily treated with a shot or a handful of pills,” Jones writes, recalling how recently-tested men displayed their City Clinic exam tickets on refrigerators and bathroom mirrors. It was a period of giddy, experimental excess. Refugees from America’s picket fence exurbs suddenly found themselves emboldened to live out whatever fantasies they’d kept closeted. “We were all creating ourselves from scratch,” he writes. “There was no map, no instructions to follow. We were all in uncharted territory and we knew it.”

Not everything was idyllic. Jones worked as a street hustler and roomed, briefly, with a half-dozen other boys in a squalid residential hotel. They dined and dashed when they couldn’t afford a meal, which was often; they sold acid, Quaaludes, and weed; and Jones often relied on the kindness of strangers to scrape by. But in the background, Jones and his crowd always sensed they were living in unique and insurgent times—an insurgency that would become contentious. Jones summarizes the schism that pitted more conservative gays against their progressive counterparts: “Are we a queer and distinct people, with revolutionary potential born from our experiences—or are we really just like everybody else except for what we do in bed?”

The claim to innateness made gay liberation both profound and deeply subversive to straight America in the 70s and 80s. The once-scandalous regalia of gay subcultures—drag, leather, the “Castro Clone” look of tight Levi’s and tighter t-shirts—and the legendary promiscuity of gay men represented something vile in the body politic. AIDS lent itself readily to metaphors of plague and invasion, as Susan Sontag famously argued, because queerness itself was repudiated as unclean and alien. Gay liberation announced our very right to exist.

All of this may seem self-evident in hindsight, but Jones’s step-by-step chronology demonstrates that gay liberation was never inevitable—progress never is. In the late 1960s and early 70s, Jones writes, “between two thousand and three thousand gay men were arrested on felony sex charges every year, almost all as a result of sexual entrapment, in hip and liberal San Francisco alone.” In addition to being social pariahs, queers were also criminals, something politicians at the time didn’t care to change. The contemporary liberal fantasy of being “on the right side of history” seems naive when applied to the LGBT movement. History doesn’t give a shit about ethics, it just steamrolls on—martyring some, shattering others, and leaving noble crusaders to throw up roadblocks. (Another recent AIDS memoir, David France’s How to Survive a Plague, documents how those crusaders pressured the scientific community to finally get involved.)

Gay liberation didn’t happen in a vacuum, and Jones is careful to situate his activism in a broader context. “When we weren’t dancing or fucking, we were marching,” he writes, ticking off the cause célèbres: Sandinistas in Nicaragua, anti-Marcos protesters in the Philippines, anti-Pinochet protesters in Chile, apartheid in South Africa, nuclear power, offshore drilling, equal pay, women’s rights. Alongside Harvey Milk, Jones and his cohorts forged coalitions with organized labor, particularly when campaigning against California’s Briggs Initiative, which would have barred gay teachers in public schools. There was a kind of relentless political ferment that the gay movement both ushered in and exploited. Then came AIDS.

Jones offers a succinct, painful caption to the pandemic: “Our friends died; we made new friends; then they died. We found new friends yet again; then watched as they died. It went on and on and on.” A thousand people in San Francisco had died of the disease by 1985, and a thousand more in the city would die every year for over a decade. The imagery of those years is seared into our national imagination, but less known are the origin stories of two of the community’s most revered symbols: the Rainbow Flag, which was the pet project of a drag queen and Vietnam Veteran named Gilbert Baker, and Jones’s AIDS Memorial Quilt, which he conceived as a therapeutic folk art project, a grassroots archive of love and grief. (“For over a year everyone told me it was the stupidest idea they’d ever heard of,” he writes.) In 1996, Bill Clinton—accompanied by Hillary—became the first president to visit the quilt when it was displayed on the National Mall. That year marked another milestone in the epidemic’s long devastation: AIDS-related deaths were down 23 percent, and 1996 was the first year that rates of opportunistic infections didn’t increase. There still wasn’t a cure, but for Jones’s generation it must have seemed that the worst was behind them. In August 1998, The Bay Area Reporter, San Francisco’s gay newspaper, announced that there were no new AIDS obituaries for the first time in more than 17 years. Jones wept as he read the headline; life was finally becoming possible.

If Jones’s generation fought for its existence, my generation has fought to market that existence. We didn’t exactly pick up where the 70s left off—the days of cheap rents and a barter economy are over—but we’ve taken the dream of Jones’s generation to its ultimate capitalist end, consolidating into a demographic with its own purchasing power and cultural cachet. When even ostensibly straight celebrities like James Franco and Nick Jonas flirt with queerness, you know that Jones’s movement has cycled from tragedy to farce. Towards the end of the book, Jones asks Dustin Lance Black, the Academy Award-winning screenwriter of Milk, what it’s like to belong to a gay generation with no purpose. Young queers, Jones writes, “seemed apathetic and unconcerned about politics. They didn’t want to talk about AIDS and seemed content to go to clubs, get high, and shop.” With same-sex marriage then on the horizon, it seemed that a live-and-let-live detente was possible.

I don’t want to dismiss Jones as a cantankerous elder statesman. On one hand, he’s right: most young queers don’t sit around pondering the legacy of AIDS, of course they’d rather fuck and shop—who wouldn’t? One person’s apathy is another’s joie de vivre. On the other hand, Jones betrays an unfortunate myopia. There’s a moment in When We Rise when Jones, talking with a friend, realizes that by 1976 there could be as many as ten million queers across America. While many were already activists or passionate about the movement, Jones doesn’t consider the millions more who were either closeted or indifferent to the political froth in San Francisco, New York, Los Angeles, and other gay epicenters.

Jones downplays the wide-angled empathy driving young queers today—what conservatives lambast as “identity politics.” I know he’s aware of this—it feels churlish to dwell on one troublesome paragraph in an otherwise inspiring book—but it’s important to press the argument. Today, young queers inclined to politics are concerned about a web of intersecting issues: transgender lives, transgender rights, LGBT homelessness, LGBT incarceration, fair labor practices, domestic violence, healthcare, affordable housing, racial justice, and many others. The mass shooting in June 2016 at Pulse nightclub in Orlando was a horrifying reminder that homophobia, even if rebranded as terrorism, still lurks in America.

But nothing solidified that horror more dramatically than the election and subsequent normalization of Donald Trump and his grab bag of anti-LGBT, sexist, racist, and xenophobic cohorts. The very presence of Mike Pence on a major party’s presidential ticket was an outrage for anyone who cares about LGBT rights. Despite Trump’s avowed—if lukewarm—tolerance of the Supreme Court’s ruling on same-sex marriage, we can’t pretend that he and his kakistocracy won’t roll back protections for LGBT workers and transgender Americans, nor can we ignore Trump’s support of the First Amendment Defense Act, which would allow vendors to deny service to LGBT people in the name of religious freedom, nor can we shrug off Pence’s nod to conversion therapy as a Midwestern eccentricity, no more extreme than a craving for sugar cream pie. The dangers ahead are real.

On a humid night after the election, I joined hundreds of protesters marching down Market Street in downtown San Francisco. As we neared the Castro and the majestic rainbow flag that flies sentinel over the neighborhood, several protesters—most in their twenties and thirties—began chanting. “If you’re trans, if you’re queer, you are welcome here!” In the Castro, where Harvey Milk lived and worked, we gathered with lit candles, placards, and rainbow banners. Jones himself was there and delivered a rousing homily: “Don’t tell me that we got through Reagan and we got through Bush, because too many of my brothers did not.” We marched in the footsteps of men who’d died 30 years before, fighting for their lives and their dignity. The symbolism wasn’t lost on anyone—it wasn’t even symbolism anymore. It was the bitter, necessary truth that history sometimes brings us back to where we started.

Young queers aren’t apathetic, but some have good reason to be. Many, especially those in San Francisco, are exhausted just trying to get by. Evictions and prohibitive rents are slowly terraforming the Castro into a playground for affluent white people. Gay neighborhoods everywhere are becoming outdoor frat houses that exploit their communities’ otherness for profit. The threat is a future of vapid circuit parties and cookie-cutter bars with few lesbians, no black or brown faces, and no young activists who can afford to live there. “Silence = Death,” the mantra of 80’s AIDS activists, has been recycled as “Eviction = Death,” a new rallying cry for the liberal resistance.

When I spoke to Jones this spring about changes in the Castro, he told me, “I’m glad Harvey Milk was cremated because he’d be spinning in his grave.” The neighborhood that Milk gave his life to create is still there, but it’s changing, and those changes matter. HBO’s Looking sought to dramatize queer life in contemporary San Francisco, but instead the show chronicled how much the city has outpaced its own history. Radical politics, committed activism, homegrown art, and music—almost none of these was integral to Looking or its characters, who wafted through the city on the tailwind of their own narcissism. Meanwhile, the series barely alluded to San Francisco’s racial and economic divide. The mostly male, mostly white cast did its earnest best with the material, but critic Keith Uhlich at the BBC summed up the show’s failure in what was meant as kudos: Looking made gay life ordinary. In the process, it offered a San Francisco that was ordinary as well, and a queer community whose audacity was reduced to a vanilla soap opera.

Jones knows that San Francisco’s moment as the capital of LGBT politics and culture is, for the most part, over, but that’s as much a marker of the movement’s success as anything. He also knows that the chapter on a certain kind of boots-on-the-ground LGBT liberation is closed, making memoirs like his all the more necessary. “My generation is disappearing,” he writes. “I want the new generations to know what our lives were like, what we fought for, what we lost, and what we won.” Jones wants his readers to know how much you can lose and how deeply you can suffer—and still declare victory.