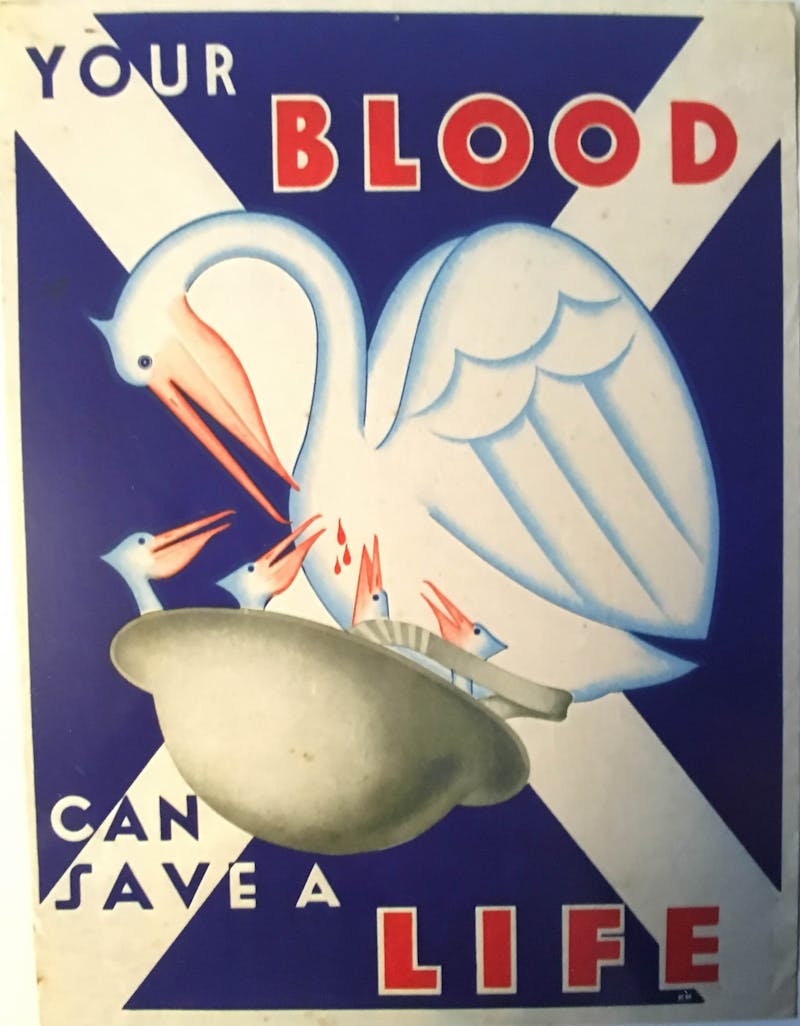

In a classic 1940s poster, a mother pelican feeds her own blood to her four happy-looking offspring. They nest in a military helmet, against a backdrop of the Scottish flag. This poster aimed to recruit donors to the Scottish National Blood Transfusion Association. The pelican image is a little opaque to us now, but in that more religious decade, the symbolism would have been clear.

Medieval encyclopedists thought that pelicans were exceptionally devoted parents, so much so that they would jab open their own breasts to feed their young on the blood. This practice of vulning (from Latin to wound, related to our word “vulnerable”) came to symbolize Christ’s sacrifice for humankind. Elizabeth I adopted the image as a cipher for her rule over England, and the bleeding pelican is a common heraldic motif.

It seems simple, the notion that old symbols help us to know our world. But it is not. What is the chain connecting the medieval illuminator who painted a bloody bird to the young Scot giving blood to save a soldier? So many wars came in between. The only constant could have been bloodshed. The pelican boils down something terribly complicated—giving one’s lifeblood to another—into a single, pretty image. We have needed it.

Likewise, we have at times needed myths and legends about miraculous rejuvenation. We are in one of those moments, and a California-based company called Ambrosia has resurrected an old tale, just in time. Founder Jesse Karmazin wants to sell the plasma and the blood of young people to older, rich people for therapeutic reasons, as Amy Maxmen reported last week in MIT’s Technology Review. The science seems wobbly at best, but the narrative—the narrative is strong. There’s a reason Silicon Valley investor Peter Thiel, a prominent Donald Trump supporter, made headlines for being young blood–curious.

Where do we get the idea that the blood of the young can heal us? The roots are complicated. The company’s name alone evokes a number of weird stories. Ambrosia was the food or drink (unclear) consumed by the Greek gods. It was delivered to them by doves, like Seamless. Supposedly, consuming ambrosia could make one immortal, hence its use as a brand I suppose. But the divine beings who consumed ambrosia did not usually have blood running in their veins. Instead, they had a fluid called Ichor. Wouldn’t that have been a more appropriate name for Karmazin’s company?

The vampire connection is easier to trace. From the folk traditions of ancient Mesopotamia and medieval central Europe to contemporary American cinema, undead beings have drunk the blood of the living. Vampires are traditionally feared and loathed, however. If the vampire merely transfused his victims’ blood into this veins via an intermediary corporation, might we have feared him less? Jeff Karmazin must hope so.

Ambrosia most explicitly recalls the story of Countess Elizabeth Báthory de Ecsed, who murdered many young women in the late sixteenth century. (Supposedly a diary recorded a death toll of 650, but she was convicted only of 80 killings.) Báthory was a noblewoman who lived in an enormous castle in what is now Hungary, where she tortured and murdered unmarried young women and, supposedly, bathed in their rejuvenating virgin blood. After her trial, Báthory was bricked into enclosement. A red gallows was built nearby to show that she had been punished.

One can only wonder at the branding decisions made in recent years by medical technology startups. Ill-fated diagnostics company Theranos powerfully recalls the Greek personification of death, Thanatos, even if it intended to combine the Greek words for “therapy” and “diagnosis.” Followers of Sigmund Freud repurposed Thanatos to refer to the death drive, the opposite of Eros, the life instinct. (There is a medical company named Eros, too: It distributes pharmaceuticals in Kenya.)

The story of the Scottish flag and the pelican shows how strangely and insistently culture drives meaning into the body. We like our stories simple, and we like them bloody. Ambrosia and other startups seeking publicity draw on those stories. As old certainties—like, say, the stability of the American government—crumble around us, we become weaker and more susceptible to the appeal of myth. When questionable tech ventures promise us unlikely rescue, whether through improbably efficient home diagnostics or the delicious blood of the young, we are tempted, even if we should know better.

Peter Thiel and his friends in the White House should smile upon Ambrosia: After all, regular bleeding should keep the young sluggish and less liable to cause trouble in the streets (or on the internet). But he should remember that even Elizabeth Báthory was caught in the end, despite her castle and her extraordinary wealth. No matter how many henchmen are at his disposal, a villain cannot live on virgin blood alone. The red gallows comes for us all.