When Republicans unexpectedly won unified control of the federal government in November, they began speaking of repealing the Affordable Care Act as fait accompli. Obamacare would be on borrowed time by the spring, replaced by the summer or fall, and wiped off the books forever within a couple years.

Three months later, their bravado has given way to panic and confusion. Republicans find themselves beset by angry and alarmed constituents at their district offices and public events every weekend. They have defensively characterized these demonstrations as paid astroturf and threats to public safety, but it is just as likely they are questioning protesters’ legitimacy to avoid confrontations like this one, between Representative John Faso of New York and a constituent with a brain tumor.

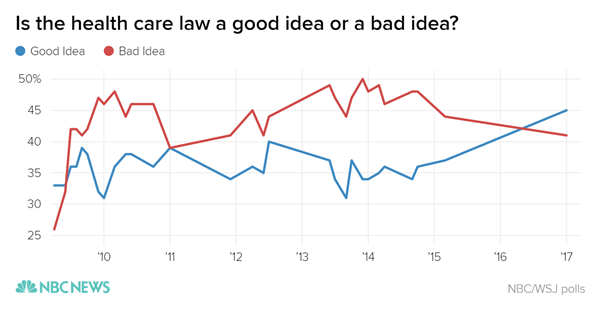

As the opportunity to build upon the ACA in a Clinton administration gave way to the reality that its coverage expansion might be reversed under President Donald Trump, its progressive skeptics—supporters of single-payer insurance or a public option—have come home, drawing its favorability above water for the first time ever.

Amid unexpected resistance, the timeline for repealing and replacing the law has slipped. In a pre–Super Bowl interview with Bill O’Reilly, Trump (who until recently promised swift and simultaneous action to repeal and replace the law) acknowledged that “maybe it’ll take till sometime into next year.” He left House Speaker Paul Ryan, Obamacare’s chief antagonist, assuring restive conservatives that the whole process would be completed by the end of 2017.

Ryan’s zen mantra clashes with the fact that Republicans are, if anything, farther from consensus on federal health policy than they were on election night. That contrast would be amusing if Republicans weren’t empowered to vandalize Obamacare or let it wither via malign neglect.

The sane solution would be for the GOP to acknowledge that their crusade against health care reform has always been more of a cynical ploy to mobilize their voters than a fact-based opposition to the policy Democrats implemented. Failing that, they could admit that the window for repeal closed in 2012, when Obama won reelection, before the ACA’s core benefits went into effect.

But Republicans feel forced by seven years of empty promises to deliver something that they can tout as repeal—without leaving millions uninsured, raising premiums and deductibles, increasing medical costs, or making any tradeoffs inimical to conservative orthodoxy. Fortunately, there’s a guidebook for escaping the trap Republicans set for themselves, and it’s one they’ve spent decades perfecting. The question is whether they can summon the common sense to use it.

These days most conservatives don’t criticize Medicare with the same vengeful antipathy they reserve for the ACA. But the truth is, conservatives never stopped thinking Medicare was a massive, freedom-destroying error. They have merely been overtaken by a broad popular consensus that the federal government should insure retirees against bankrupting medical costs and premature death.

As part of a campaign against Medicare called Operation Coffee Cup, the American Medical Association enlisted Ronald Reagan in 1961 to deliver an address warning that Medicare might ultimately lead to left-wing dictatorship.

By the time he became president 20 years later, Reagan had made an uneasy peace with the retirement programs of the New Deal and Great Society. Tinkering around their edges, as he did, was an implicit admission that the road to serfdom he’d warned about was really just unfounded hysteria.

But the ideological right kept up the fight. In the 1990s, House Speaker Newt Gingrich famously supported reforms he hoped would cause Medicare to “wither on the vine.” Before he became speaker, Paul Ryan embraced similar ideas, which made him a darling of the conservative movement during the Obama years. But like Reagan, Ryan recognized that a frontal assault on Medicare would backfire horribly. As chairman of the budget committee and now as speaker, he has proposed to phase out Medicare slowly, and only to begin the process after 10 years. The GOP sales pitch for Medicare privatization rests on the promise (unsupportable in the long run) that they won’t touch benefits as they exist today for anyone in or near retirement.

That hasn’t enticed Democrats to support the Ryan plan, but it has lowered the stakes enough to gain overwhelming buy-in from the the GOP rank and file, and take the sting out of commonplace liberal objections. After all, even if Republicans want to “end Medicare as we know it,” a phased-in phaseout would give Democrats 10 years to regain power and undo the entire scheme before it began to take effect.

It would be better for all involved if Republicans simply joined the international welfare state consensus that includes basically every other conservative party in every advanced democracy in the world. But failing that, it would be a modest improvement on the status quo if they applied their backdoor strategy to privatize old-age benefit programs to their ongoing efforts to end the Obamacare coverage guarantee for working-age people.

Such a repeal blueprint would promise: no changes for current beneficiaries; no changes for the next 10 years’ worth of beneficiaries; and the sketch of a new program for those who will reach working age in 2027. This would do much less to spook insurers, providers, beneficiaries, and other stakeholders than Republicans are doing right now. And it would be consistent with the approach conservatives have taken to rolling back broad-based benefit programs more generally. If Republicans can abandon their Obama revenge fantasies, and start accepting the ACA as an entitlement for the middle class, they might even be able to fulfill their repeal promise without creating a humanitarian crisis.