During the presidential campaign, Donald Trump rose to the top by needling his opponents with crude but effective nicknames: Lyin’ Ted, Little Marco, Low-Energy Jeb, and Crooked Hillary. His stage persona resembled a blustery, bullying stand-up comedian. “Trump was a hot comic, a classic Howard Stern guest,” New Yorker television critic Emily Nussbaum recently wrote. “He was the insult comic, the stadium act, the ratings-obsessed headliner who shouted down hecklers. His rallies boiled with rage and laughter, which were hard to tell apart.”

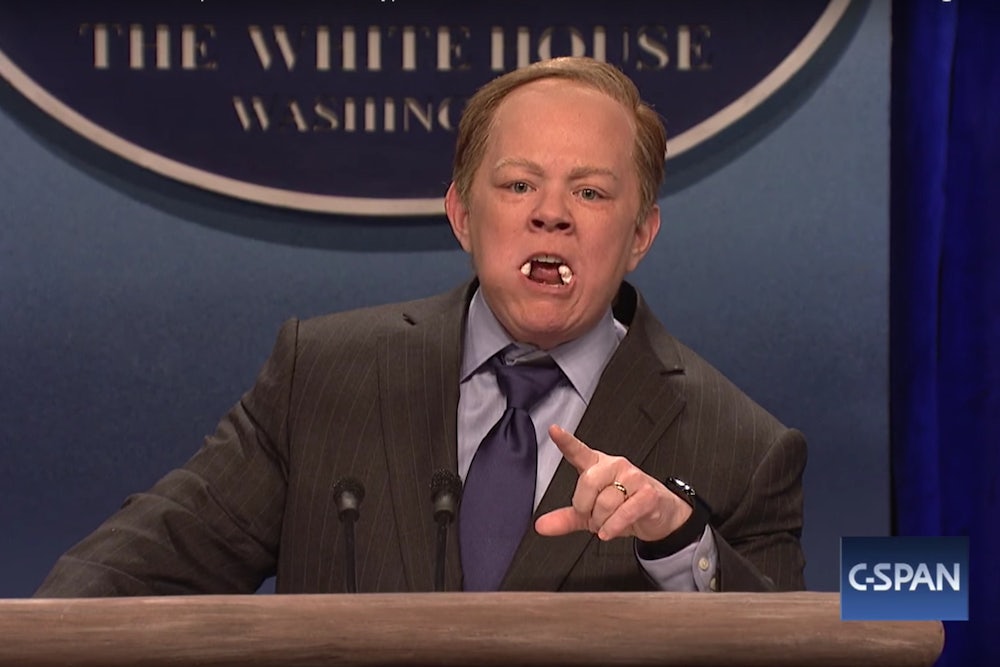

But in comedy, as in so many other areas, Trump believes in a double standard: He’s allowed to make fun of you, but don’t you dare make fun of him or his stack. On Twitter, he’s repeatedly attacked Alec Baldwin’s Saturday Night Live parody of him as a dimwit easily manipulated by Russian President Vladimir Putin and top adviser Steve Bannon. “Not funny, cast is terrible, always a complete hit job,” read one tweet. Trump is also reportedly upset over an SNL skit where Melissa McCarthy imitated Sean Spicer, Trump’s hot-tempered press secretary. “More than being lampooned as a press secretary who makes up facts,” Politico reported, “it was Spicer’s portrayal by a woman that was most problematic in the president’s eyes, according to sources close to him.”

Trump’s manifest thin skin has led some of his opponents to argue that comedy is the perfect weapon to defeat the president. “He’s affected by comedy!” documentary filmmaker Michael Moore told a rally on the eve of Trump’s inauguration. “If you make fun of him, if you ridicule him, or if you just show that he’s not popular … I’m telling you, my friends, this is how he’ll implode. This is his Achilles’ heel … Participate in the ridicule and the satire for the emperor who has no clothes. Let’s form an army of comedy and we will bring him down.” Moore’s optimism that humor can topple Trump is at odds with Nussbaum’s pessimistic conclusion—reflected in the title of her essay, “How Jokes Won the Election”—that it was comedy that propelled Trump to the White House in the first place.

This contrast reflects a broader debate about the role of political comedy today, which, since the election, has centered around one question: “Do jokes help or hurt Trump?” But this question requires less an answer than a re-framing. To expect comedy to have a decisive political impact is to miss the point of humor. Jokes, even political jokes, aren’t about persuasion, but rather psychological comfort in the face of difficult or painful situations.

The liberal hope that comedy can defeat Trump is best exemplified in the recent boosterism of Al Franken, the Minnesota senator and former Saturday Night Live regular who has regularly made headlines with his tough questioning of Trump’s cabinet nominee. National Journal’s Josh Kraushaar argued that “with many Democrats arguing that they need their own famous face to challenge Trump, Franken fits the bill as well as anyone.” “I think being a celebrity (and a comic to boot!),” Chris Cillizza of The Washington Post wrote, “is a giant asset when running against Trump.” And the New Republic’s Graham Vyse made this case:

As a decimated Democratic Party looks for leadership in the shadow of a unified Republican government—one led by a part-time TV producer—there are calls for Franken to harness his talent as a public entertainer and take on Trump as only he could: with devastating wit. Franken should heed these calls...

Franken may well be the smart play for Democrats in 2020, but it’s not because his humor can somehow slay the sitting president. Satirists, after all, are flummoxed by Trump because he’s a caricature himself. South Park co-creator Trey Parker recently sounded a defeated note: “It’s tricky now because satire has become reality. It’s really hard to make fun of and in the last season of South Park, which just ended a month and a half ago, we were really trying to make fun of what was going on but we couldn’t keep up, and what was actually happening was much funnier than anything we could come up with.” South Park proved better at foreshadowing our political moment than satirizing it. “What [the show] did get,” Nussbaum wrote, “was how dangerous it could be for voters to feel shamed and censored—and how quickly a liberating joke could corkscrew into a weapon.”

Some have argued that liberal political comedians played a major role in the shaming of these voters—indeed, that the likes of Stephen Colbert, Jon Stewart, and John Oliver were even to blame for Trump’s rise. Jesse Bernstein, at Tablet, wrote that Stewart and Colbert “helped to create the very specific type of internet-era liberal smugness (and, consequently, ignorance) that, though far from the sole cause by any means, has been a significant factor in both the rise of Trump and our current political fracturing. In Columbia Journalism Review, Lee Siegel argued that “it was Stewart and Colbert who helped create the atmosphere of “fake news” (formerly known as gossip, rumor, dis-, or misinformation) that helped elect Trump, and that currently has the media up in arms.” Some have taken the opposite position: that Hillary Clinton would be president if Stewart hadn’t stepped down from The Daily Show in 2015.

These takes misunderstand the power and virtues of comedy. “Fans of political satire tend to think that if only someone dares speak out, something will change, the powerful will flip out, and, faced with a hilarious and unanswerable exposure of their misdeeds, the pols will reverse policy,” Ben Schwartz wrote in The Baffler a few years ago. “In the right moment, in the right place, satire can still alter perception and change the conversation. The difference today is that politicians and policy apparatchiks now understand this as well as the comedians. Whether satire is ‘devastating’ or not, whether the powerful can survive it or not, perhaps isn’t the point. There’s no joke or movie that can topple a president.”

The case against comedy was made most effectively by the British writer and painter Wyndham Lewis in his remarkable 1918 novel Tarr, where the protagonist says:

The University of Humour ... that prevails everywhere in England for the formation of youth, provides you with nothing but a first-rate meaning of evading reality. All english training is a system of deadening feeling, a stoic prescription—a humorous stoicism is the anglo-saxon philosophy. Many of the results are excellent; it saves from gush in many cases; in times of crisis or misfortune it is an excellent armour ... But for the sake of this wonderful panacea—english humour—the English sacrifice so much.

Lewis was anti-comedy, but his observations help us appreciate the real role comedy plays in helping to contain pain. Mikita Brottman, a humanities professor at the Maryland Institute College of Art, made a similar case in her 2004 book Funny Peculiar: Gershon Legman and the Psychopathology of Humor, where she asked if “it is possible that human laughter is connected not to feelings of good will at all, but to a nexus of deep emotions revolving around fear, aggression, shame, anxiety and neurosis?” (She answered yes.)

If, as Lewis’s protagonist argued, humor is an “armour” against unspeakable feelings, then we need jokes more than ever in the Trump era, as protection from a president whose erratic authoritarianism is deeply scary and upsetting. “I don’t think partisan comedy helps candidates get elected,” Conan writer Laurie Kilmartin told New York magazine recently, “but it does help the audience get through it. John Oliver and Sam Bee are great, but after you finish laughing, you still have to vote.”

Aside from keeping Trump opponents psychologically balanced, jokes have the pleasant side effect of keeping Trump himself unbalanced. As Yahoo TV critic Ken Tucker noted, Saturday Night Live skits increasingly seemed pitched at the narrowest possible niche audience of one: Trump himself. Tucker sees this as a negative:

[T]he McCarthy sketch was a vivid example of the way SNL (along with the cable news channels) are now directing their satire directly at our TV-obsessed president. We, the viewers, have become almost incidental bystanders. That’s one reason the Alec-Baldwin-as-Trump sketches have been falling flat: They’re so stuffed with quotations from Trump emanating from Baldwin’s orange puff-pastry face that writing jokes for the audience to laugh at seems to be a minor concern or abandoned entirely. Just as Baldwin trolls Trump on Twitter, baiting him for attention, so do the SNL sketches yearningly seek Trump’s tweet-censure.

That these jokes aren’t terribly funny—at least not to the same degree as Trump’s own Twitter feed—is almost beside the point. They’re designed not to make the audience laugh, but to make Trump feel like he’s being laughed at. As such, this humor is closer to Trump’s own form of insult comedy than anything else, and perhaps that’s why it so obviously stings him. Trump’s opponents should feel a sort of communal comfort in the knowledge that these jokes are hitting their intended target. Will this comedy help to take down Trump in 2020? Not likely. But will it help us get through the next four years? Most certainly.