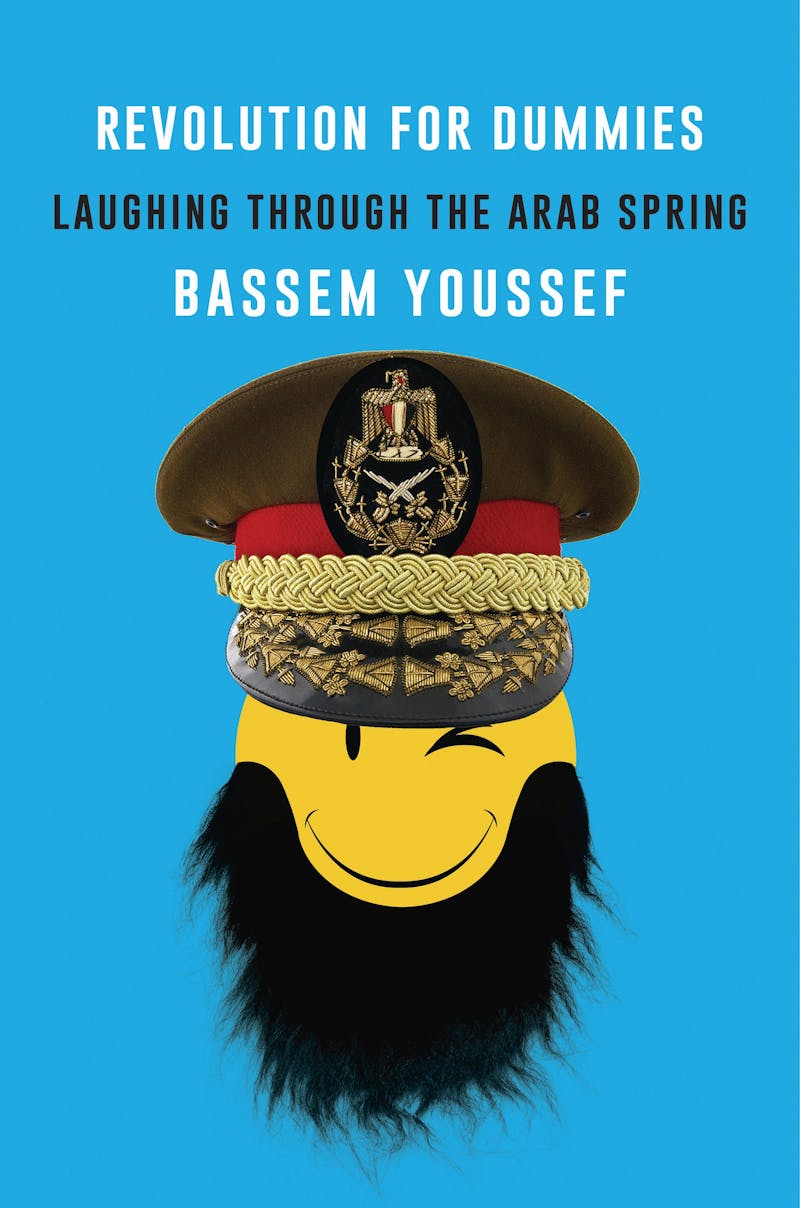

This is how the book begins, as so many sagas in the Middle East do: Panic on the way to the airport. Praying your name doesn’t show up on a no-fly list. Dr. Bassem Youssef writes: “Destination: Dubai. Destiny: Unknown.” His crime? Making people laugh.

Years before his 2014 escape from Egypt, Youssef, a cardiologist, was in the business of healing hearts. But the Arab Spring shifted the soil beneath him. He was a newlywed in 2011, with piercing blue eyes and a sharp wit. And like everyone else, he was at his wit’s end. He spent his nights operating on wounded protesters in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, but he didn’t feel like he was doing enough. So a few months later, he did what everyone with an internet connection and an obsession with Jon Stewart’s The Daily Show did back then: He started his own YouTube channel. He soon found that he could mend hearts in a different way.

Political satire was rare in the Arab world at that time, so his show was revolutionary from the moment it first aired. Egyptians have a history of inserting political comedy into films and plays, but its autocratic leaders were usually not the direct butt of these jokes. In the spirit of The Daily Show, Youssef kept it simple and named it Al-Bernameg, or The Show. In these early clips, he mocked authority figures in the country, including the longtime strongman Hosni Mubarak, airing his country’s dirty laundry from his home’s actual laundry room.

Eventually, he had to assemble a team to help with the writing, so he scanned Facebook and Twitter and hired people who left funny comments on relevant posts. Nobody knew what they were doing, but they were doing something. The low-budget production quickly attracted five million viewers an episode, and, soon after, landed him a lucrative TV deal.

But while his dreams were starting to come true, so were his nightmares. Youssef’s rise and fall almost directly mirrors the wild swings in Egypt’s recent history. Not everyone was happy about the way he joked about serious matters. He jabbed at Hosni Mubarak, and when Mubarak fell he jabbed at his democratically elected successor, Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood. He saved his best material for Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, the military leader who took office in 2014 as the counter-revolution swept away Morsi and all the gains that Egypt’s people power movement had made. The Sisi people were really unhappy with Youssef. After intense pressure, lawsuits, arrests, and stalled production, the show was canceled. Youssef’s father was mysteriously killed in a car accident. Youssef left the country before he could get arrested again.

Al-Bernameg was Egypt’s first political satire show in Arabic made entirely by Egyptians, for Egyptians. Perhaps it will be the country’s last. After all, Youssef showed that comedy is no laughing matter.

One of the reasons the show was such a sensation was that people from all different parts of the country could access his jokes. Illiteracy rates are high in Egypt, so comedy on a smartphone was a great unifier. Hoping to control the stream of unfiltered information, the government shut down phone lines and internet when the Arab Spring started. But it backfired. People flooded the streets to find out what was going on. Many say that Tahrir Square became such a hotspot because people literally got stuck there. Traffic was so congested, it was easier to just stay put.

Youssef was there. He had a small portable camera and filmed people in the heart of the square. When the episode aired, the audience was holding on to each word he spoke. It wasn’t only because he was funny; it was because he dared to say anything at all. Later, when his popularity grew and his confidence peaked, he mocked Morsi’s poor English when the leader said, “Gas and alcohol don’t mix,” evidently meaning, “Don’t drink and drive.” Youssef said to his audience: “No, he’s right. Alcohol and gas don’t mix ... like religion and politics don’t mix.... The liar goes to the fire, and sometimes, even becomes president. Not in Egypt, necessarily. In other places, I mean!”

He certainly didn’t claim to be an expert on the policies of the region. For that, “you can read one of those boring books published by Washington think tanks or political science departments in fancy Ivy League universities,” he writes in his book. He was much more than that, and everyone knew it. Youssef was asked to appear on The Daily Show in New York in 2012. Stewart then came to Egypt and was a guest on Al-Bernameg. At the height of its popularity, Youssef’s show was drawing 30 million viewers a week. (Jon Stewart’s most popular The Daily Show episode, his finale, took in five million viewers.) Youssef was named one of Time’s Most Influential People in 2013 and was awarded the International Press Freedom Award by the Committee to Protect Journalists that same year.

By 2014, Sisi had his name plastered on walls all over Egypt; his image was on chocolate wrappers and clothing. The military and Sisi himself were heroes to some, dictators to others. They went after Youssef, interrogating him for six hours and arresting family members of his crew to intimidate him into silence. Perhaps one of the most ludicrous examples of this persecution was when a fictional character, a puppet named Aunt Fahita (who has her own verified account on Twitter), was put on trial.

Sisi and Co. clearly felt threatened. As Youssef explains, “When you laugh, you are not afraid anymore. Dictators are afraid of jokers. Laughing in the face of tyranny and fear, disarms them in front of their supporters.... They come back to you with all their might because it is much more than their image or dignity that they want to preserve: Their legitimacy is at stake.”

The fact that he was forced to end his show after three turbulent years was the ultimate indicator that he was making a big impact in the political world. On his final taping, while holding a handwritten placard that read “The End,” Youssef said that “pulling the show off the air is a victory.”

Youssef is now living in Los Angeles. Armed with a green card, with his wife and daughter by his side, he is trying out his luck in Jon Stewart’s America. His material is now in English. But like other exiled political dissidents before him, he will have to face the fact that his clout back home will diminish now that he’s no longer a threat to the regime. Meanwhile, the novelty of his act will still suffer from an oversaturated American market, where political satire is virtually an industry unto itself. But there are some signs that his influence remains. Sisi’s hecklers-for-hire have recently been spotted at Youssef’s appearances in New York.

Meanwhile, Sisi prepares for a state visit with President Donald Trump this week. Hosni Mubarak has been freed from hospital detention, the last nail in the coffin of the Egyptian revolution. Youssef no longer has a show, but he has this memoir and a new documentary, Tickling Giants, about his rise and fall. There are still jokes to tell, if anyone is willing to listen.