Congressional Democrats kicked off the first term of the Obama administration having controlled the House and Senate for just two years. Consecutive landslide elections, in 2006 and 2008, left their caucuses overrun with unseasoned legislators, steeped in opposition politics and beset by conflicting priorities. Yet somehow they devised and passed the most far-reaching legislative agenda in half a century, without the luxury of a cooling off period.

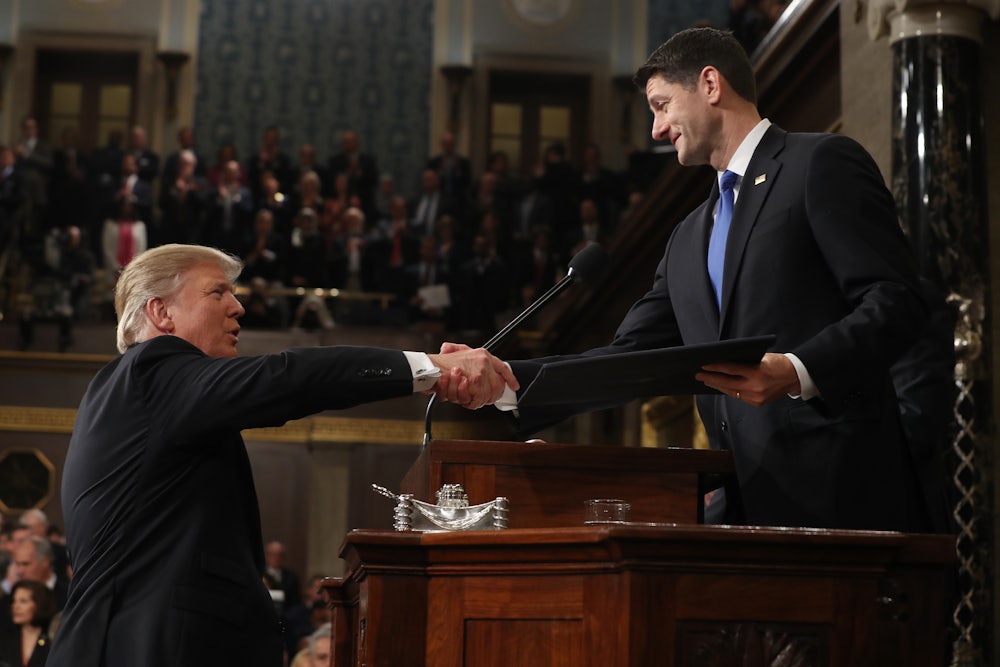

As Paul Ryan sees it, this was some kind of miracle. At a Capitol briefing on Friday, he explained the failure of the GOP’s American Health Care Act as a consequence of “growing pains” that come with “moving from an opposition party to a governing party.”

This is a comforting thought for a House speaker who, despite Republican control of all levers of government, is staring into the policy void. But as the Democratic majorities of 2009 and 2010 show, “growing pains” are not an immutable fact of legislative politics. Republicans controlled the House for six years, and the Senate for two, before Donald Trump became president. If anything, the transition from opposing to governing should’ve been easier for them than it was for Democrats eight years ago. And yet it is proving much harder.

There is a coherent story that explains why Republicans, at their historical apex of power, are also historically dysfunctional, and health care is a huge part of it. But it isn’t a story Ryan will be able to piece together until he accepts the central role he played in it.

If a party can move from opposition to governing fairly seamlessly, why couldn’t the GOP? The differences between 2009-era Democrats and 2017-era Republicans lie to a large extent in each party’s conduct while toiling in opposition.

In Ryan’s mind, all opposition is total and unscrupulous.

“We were a 10-year opposition party, where being against things was easy to do,” he acknowledged at the same press conference. “You just had to be against it. And now in three months’ time we tried to go to a governing party where we actually had to get 216 people to agree with each other on how we do things and we weren’t just quite there today. We will get there.”

This is a false construct, a way to rationalize dysfunction as akin to rust—an inevitable consequence of powerlessness, rather than the completely avoidable consequence of years of disgraceful behavior. There is a more nuanced version of the 10-years-out-of-power story that doesn’t write Republican agency out of the equation, and thus homes in on the single root of their electoral success and factional incoherence.

“[I]t has been nearly a decade since Washington Republicans were in the business of actual governance,” wrote The Atlantic’s McKay Coppins, echoing Ryan. “Whether you view their actions as a dystopian descent into cynical obstructionism or a heroic crusade against a left-wing menace, the GOP spent the Obama years defining itself—deliberately, and thoroughly—in opposition to the last president. Rather than engage the Obama White House in a more traditional legislative process—trading favors, making deals, seeking out areas where their interests align—conservatives in Congress opted to boycott the bargaining table altogether.”

This cuts closer to the truth, but it presents the question of whether Republicans behaved cynically or in principled fashion as a subjective matter, when it is anything but. There has been no shortage of evidence confirming that Republican leaders in 2008 settled on an opposition strategy of massive resistance before Obama took the oath of office. Obama could conceivably have advanced an agenda that was so ideologically unpalatable that it retroactively vindicated Republican cynicism. Instead, Obama seized the center, and many Republican members had to be strong-armed into uniform opposition—including to the Affordable Care Act.

The depiction of Obamacare as a many-tendriled monster strangling human liberty was not the GOP’s instinctive, ideological reaction to the bill, but an outgrowth of a strategic choice the party made to deny Obama any claim to having forged consensus. This decision led to a number of awkward reversals, such as when GOP leaders and right-wing propagandists drove Senator Chuck Grassley from acknowledging a “bipartisan consensus to have individual mandates” to validating death-panel conspiracy theories in a matter of weeks.

The upshots of adopting such an absolutist facade can be strung together into a fateful parable of sunk costs. Seven years later, it is still impossible for Republicans to admit that, contrary to their initial portrayal, Obamacare is simply what a market-oriented national health insurance system looks like. By closing off the one avenue by which transactional Republicans might forge a health care detente, people like Paul Ryan guaranteed the entire party an eventual reckoning with the basic idea that every American deserves affordable medical care.

Rather than make the unpopular counterargument, and oppose the Affordable Care Act on the basis of ideological differences, Republicans adopted an unprincipled strategy of attacking and promising to remedy the law’s every weakness—even when their promises cut against conservative orthodoxy.

“Obamacare was a useful tool for them,” the conservative writer Philip Klein wrote Friday in a withering critique. “For years, they could use it to score short-term messaging victories. People are steamed about high premiums? We’ll message on that today. People are angry about losing insurance coverage? We’ll put out a devastating YouTube video about that. Seniors are angry about the Medicare cuts? Let’s tweet about it. High deductibles are unpopular? We’ll issue an email fact sheet. Or maybe a gif. At no point were they willing to do the hard work of hashing out their intraparty policy differences and developing a coherent health agenda or of challenging the central liberal case for universal coverage.”

Klein called Republicans “a party without a purpose,” but it is just as likely that they are a party that put achievable goals out of reach by indulging in expedient pandering. Their plan’s only weakness was that it might some day end in success. Trump in particular embodies the real but temporary political advantages of shamelessness. Politicians who win by saying anything will be expected to deliver everything.

This isn’t just a story about the contradictions between Trump’s fraudulent campaign and his denuded administration. It’s the story of how the ruthless pursuit of power left an entire party unable to exercise it now that it’s theirs.