David Lynch: The Art Life, directed by Jon Nguyen, is a new documentary about everybody’s favorite deluxe-coiffed director. Lynch himself narrates the film, looking back on his childhood and early life from his current perch of success. We begin somewhere near a happy memory of splashing in a mud puddle with a pal and end around the Los Angeles residency that led to Lynch’s first feature-length movie, Eraserhead, with contemporary footage as frame. In the present day, we see Lynch sitting alone at home, often staring into the dark with eyes unfocused beneath the quiff.

Fans of the Lynch oeuvre may be surprised at the central role painting has played in his life. Lynch worked for years at a studio owned by the father of a friend, then at art school in Boston. He dropped out after a year, then attempted a pilgrimage to Salzburg with his friend Jack Fisk (whose sister he later married), trying to track down Oskar Kokoschka. They came home disappointed after two weeks.

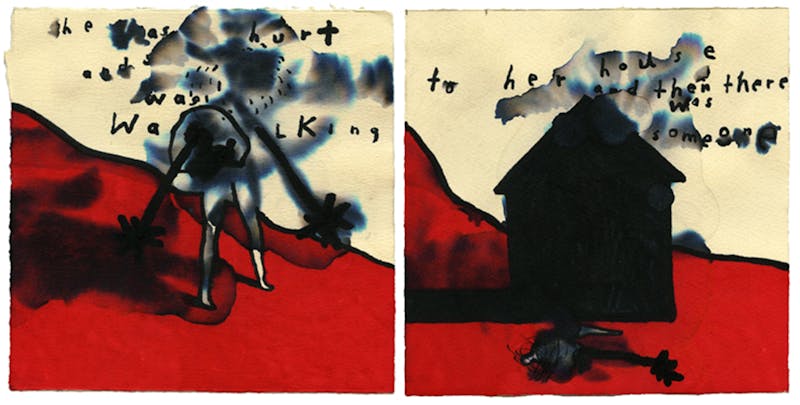

Lynch’s artwork has some consistent themes. He features his own handwriting quite a lot—it’s a crabbed hand, using widely-spaced lettering of the kind most often seen on album covers of the 1990s. They tend to relate cryptically to bodies. Odd textures are applied to their surfaces, as if expressing physical pain. Human subjects are often given elongated limbs or bent into excruciating shapes. The paintings are surprisingly unlike his movies, to my eye, because they are unglamorous. There’s no slinky minimalism to them.

Although the documentary focuses on Lynch’s painting career, cutting between reminiscences and footage of him at work in his home studio, working latex into an ochre painting, its cinematography is heavily informed by the subject’s film technique. The soundtrack is predominantly by Lynch himself, dirging along in his signature drone-blues register. The shots are often long and contain somewhat frustrating (or just Lynchian?) pauses in which nothing happens.

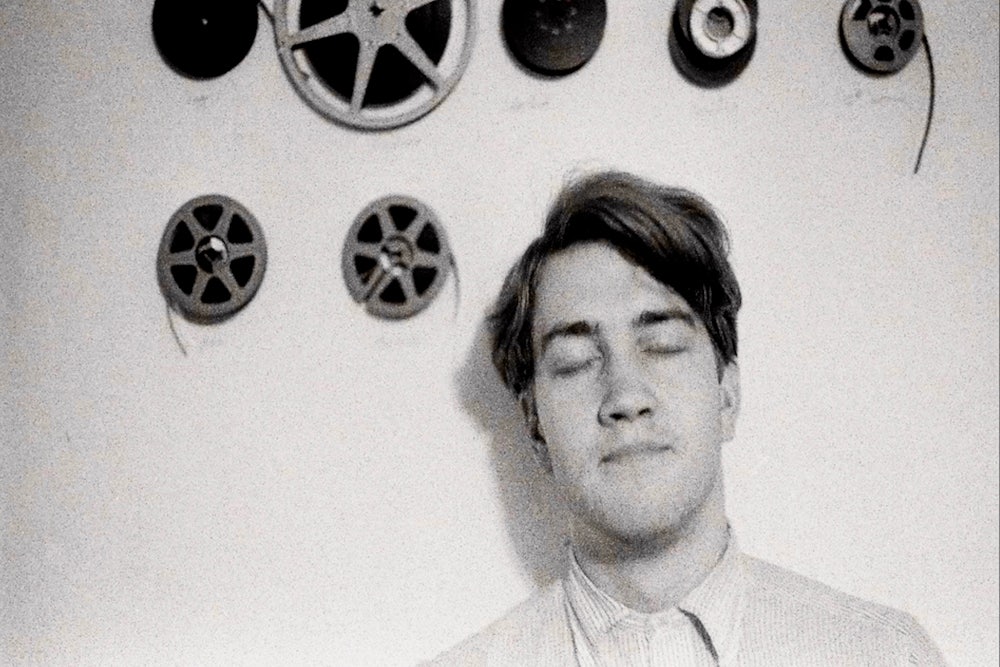

Footage of Lynch as a young man makes delicious watching for a fan. He looks so different. Without his signature undercut, the whole shape of his head seems wrong. He always had that thousand-yard stare—as if looking over the top of everybody’s head—but it didn’t used to be so stylish. Clad in classic art-school garb (striped shirts, buttoned high) David Lynch looks like any other painter scraping by in Philadelphia. He’s pudgy, almost Wildean.

In Philadelphia, before his film career began, Lynch was married. His wife Peggy was the actress in Alphabet (1968):

Peggy and Lynch had a daughter together, Jennifer. When Lynch received a life-changing residency at L.A.’s AFI Conservatory, they all moved out there together. But soon into the production of Eraserhead, the couple divorced. This part of the documentary is quite strange, since Lynch implies that all the chaos of family life was somehow distracting, or making him unhappy. Though he is unclear on this part of his life, Lynch doesn’t come off very well. In the documentary, we see the gray-haired man’s new daughter Lula Boginia Lynch toddle around, drawing alongside him. The juxtaposition is a little strange; Lynch reminiscing about his first family ambivalently while enjoying his new one. But it’s not so new for David Lynch to baffle us.

David Lynch: The Art Life moves a little slowly, and is perhaps over-inflected with the Lynchian style of showing a life onscreen. But Lynch’s insights into his own past are fascinating: The way he describes splashing in that mud puddle is just exquisite. In a past interview, Lynch described his paintings as “organic comedies.” In this sense they work against the movies, which are made with artifice and delicacy. For sheer curiosity’s sake and in the name of understanding an underexamined part of this dense and fantastic brain, this documentary is required viewing.

“David Lynch: The Art Life” opens at New York’s IFC Center March 31 and at Los Angeles’s Cinefamily on April 14.