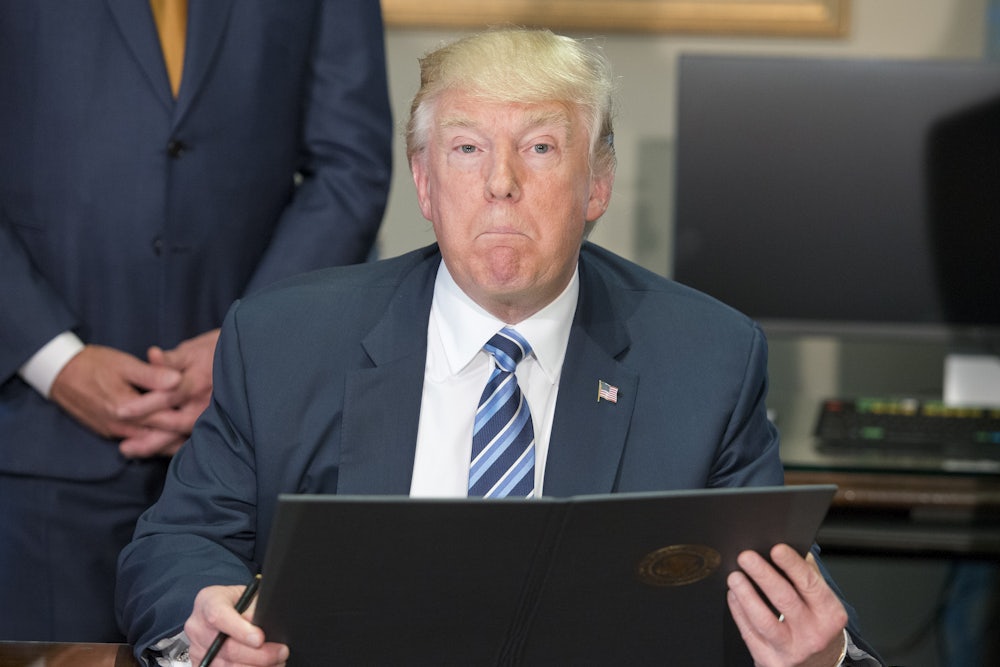

President Donald Trump wants to hedge his bets about how his first 100 days should be judged, claiming great victories while also suggesting—with his customary scorn for consistency—that the 100-day metric is artificial and should be disregarded. “I’ve done more than any other president in the first 100 days and I think the first 100 days is an artificial barrier,” Trump told the Associated Press in an interview released Sunday, ahead of a momentous week when Republicans will try (again) to pass the American Health Care Act while also funding the government (and perhaps a border wall) by Friday’s deadline. It’s entirely possible that come Saturday, Trump’s 100th day in office, he will have shut down his own government.

But even if that doesn’t come to pass, Trump’s first months in office have been unquestionably rocky. He kept his promise to fill the late Justice Antonin Scalia’s seat with an equally conservative justice (Neil Gorsuch), but otherwise his agenda has stalled. The first attempt to “repeal and replace” Obamacare failed to secure enough Republican support to even get a vote in the House, while nine other promised pieces of legislation (ranging from the Middle Class Tax Relief and Simplification Act to the Affordable Childcare and Eldercare Act) are nowhere to be seen. With the administration rocked by internal divisions, and cabinet appointees at times hostile to his stated policies, Trump has been forced to cede ground on major planks of his “America First” agenda: NATO is no longer obsolete, Trump admits, nor is China a currency manipulator.

Yet Trump’s critics would be foolish to crow over his defeats. For he has been able to advance his vision of the world through his very incompetence, which will fulfill his goal of radically transforming America while also leaving a permanent stain on the nation’s reputation.

“Lenin wanted to destroy the state, and that’s my goal too,” Steve Bannon, who helped shape Trump’s ethno-nationalist campaign and now serves as his chief strategist, once said. “I want to bring everything crashing down, and destroy all of today’s establishment.” If bringing everything “crashing down” is not just Bannon’s goal, but also Trump’s, then his first 100 days have been as consequential as that of any president in history.

Consider immigration. It’s true that the federal courts have struck down Trump’s executive order limiting immigration from seven predominately Muslim countries. Yet this policy defeat has to be contrasted with the real-world impact of Trump’s xenophobic rhetoric. “Generations of Indians have admired the United States for almost everything. But many are infuriated and unnerved by what they see as a wave of racist violence under President Trump, souring America’s allure,” The New York Times reported on Sunday, noting that “undergraduate applications from India fell at 26 percent of United States educational institutions, and 15 percent of graduate programs.”

Bannon has expressed concern that “two thirds or three quarters of the CEOs in Silicon Valley are from South Asia or from Asia.” As a practical matter, if your goal is to keep America as white as possible, discouraging potential immigrants from coming is as big a win as stopping them at the border.

Limiting immigration by tarnishing America’s international reputation is a sort of catastrophic success: the achievement of a policy goal through actions that are also self-defeating. Trump’s first 100 days have had many such successes, such as the administration’s mistreatment of Sahar Nowrouzzadeh, a U.S.-born career civil servant moved out of a top advisory position after right-wing outlets like Breitbart and the Conservative Review attacked her with reports suggesting she was aiding the Iranian regime. By shuffling Nowrouzzadeh from her position, the White House has legitimized these attacks, which is both a success for Trump’s brand of xenophobic nationalism and a failure for the ideal that civil servants are non-partisan experts protected from political retaliation.

Trump has also had catastrophic success in foreign policy. It’s true that he had to retreat from a full-throttle “America First” agenda, in large part because of pushback from his own appointees, such as Secretary of Defense James Mattis and national security adviser H. R. McMaster. Yet even as Mattis and McMaster strive to shore up existing alliances, Trump’s erratic behavior and often strange statements are shaking the faith of America’s allies.

A bizarre incident earlier this month shows how easy it is for an inept president to tarnish America’s reputation. The Trump administration claimed that the U.S. aircraft carrier Carl Vinson was headed toward the Korean Peninsula, but it turned out the ship was 3,500 miles away and headed in the opposite direction. As The New York Times reports, “South Koreans felt bewildered, cheated and manipulated by the United States, their country’s most important ally.” An article in the South Korean newspaper JoongAng Ilbo compared the United States to North Korea, asking, “Like North Korea, which is often accused of displaying fake missiles during military parades, is the United States, too, now employing ‘bluffing’ as its North Korea policy?”

The South Koreans are not alone in asking themselves whether America can still be trusted. Gareth Evans, the former foreign minister of Australia, described Trump as “the most ill-informed, under-prepared, ethically challenged and psychologically ill-equipped president in U.S. history,” and suggested that Australia might be wise to pursue a closer relationship with China. For those who adhere to the internationalism that has guided American foreign policy since the early 1940s, these sorts of critiques from close allies are seen as failures. But for Trump, Bannon, and others who believe in an “America First” foreign policy, such alienation furthers their goals: It weakens alliance systems, making it easier for the U.S. to pursue unilateral action.

Trump’s first 100 days have been full of hidden triumphs of this sort—destructive decisions and apparent screw-ups that nonetheless further his agenda. Even as his legislative agenda stalls, Trump is turning out to be a consequential president whose catastrophic legacy will outlive his tenure. After all, how will it be possible to regain international trust in America and its institutions after the country was so foolish as to elect a man like Trump as president?

Some might argue that it won’t be so difficult to restore America’s reputation. Many American allies who were unhappy with George W. Bush’s presidency rediscovered their faith in America when Barack Obama was elected. But Bush, as unpopular as he was internationally, was a very different president than Trump. There’s a crucial distinction between having bad policies and being chaotic. The former can be reversed, while the latter raises fears about reliability over the long haul. Even if a post-Trump president offers reassurances to allies and returns America to old norms, the citizens of nations like Australia and South Korea might reasonably ask themselves how long such a reversion can last. After all, a nation that elected Trump could be expected to elect similarly erratic presidents in the future. He is scrambling the cost/benefit analysis for our key allies, such that some might seek more reliable partners or become more independent.

From Vietnam to Iraq, America has recovered from bad policies before. But in the modern era, the nation has never had a president like Trump, who subverts faith in the its institutions and in the ideal of America as a country worth aspiring to. Whatever policies he manages to implement won’t do nearly the same damage as his inherent chaos, which is most successfully advancing his goal of an ultra-nationalist America that scorns immigrants and allies alike.