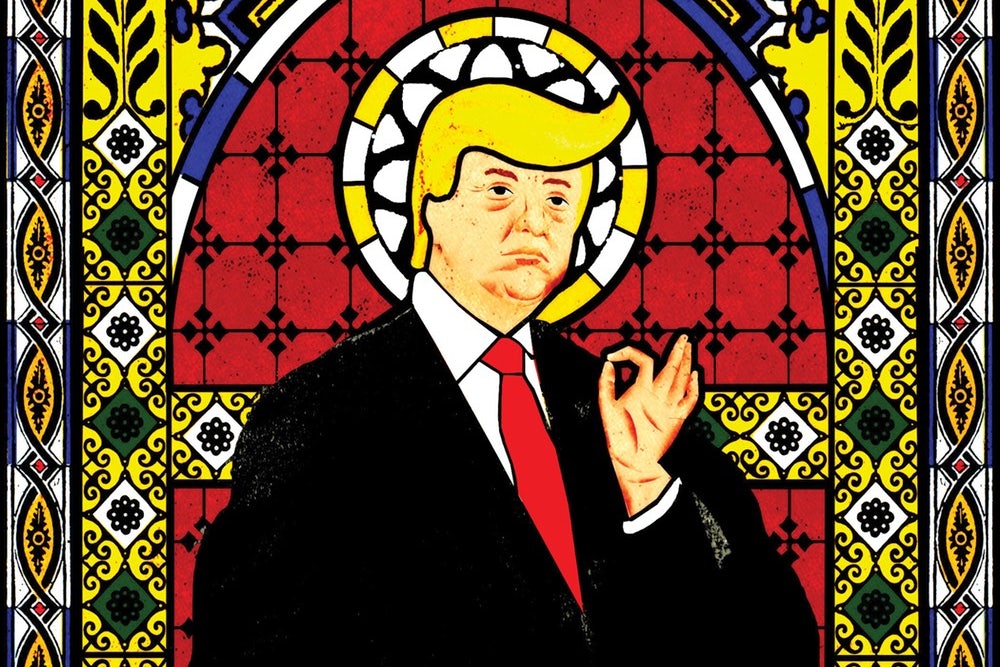

Every four years, American political journalists, who rarely interest themselves in spiritual matters outside of election cycles, act out their own sort of religious ritual: foretelling “the evangelical vote.” Think back to February 2016, after Donald Trump had won his large victory in the Republican primary in New Hampshire, but before South Carolina had voted. He was not supposed to win that state, because there are a lot of evangelicals there, and evangelicals, our soothsayers told us, did not like Donald Trump. They did not like him because he was Donald Trump, and we all know that story, but also because he mistakenly referred to “Two Corinthians” instead of “Second Corinthians” when he spoke to evangelicals at Liberty University.

As it turned out, Trump’s biblical mishap didn’t matter. He won South Carolina handily, and went on to capture 81 percent of the white evangelical vote in November, beating the previous high of 78 percent for George W. Bush in 2004. (By comparison, Ronald Reagan won only 67 percent of evangelicals, and Jimmy Carter—a Southern Baptist whose candidacy marked for many secular observers the emergence of evangelicalism as a political force—won even fewer.) The outcome called into question plenty of assumptions about evangelicals and their political agenda. How could the so-called “Christian Right,” believed to vote according to a fiercely moral agenda, embrace the most impious presidential candidate in American history?

Frances FitzGerald’s new book, The Evangelicals, would seem to be one that might explain to secular readers this puzzling turn of events. She opens with Carter as the beginning of the modern evangelical presidential era, and concludes with Trump, whose very nomination was supposed to be that era’s tombstone. In between she sweeps through nearly three centuries of American religious history. She draws on her long experience of modern evangelical politics, which she has chronicled for four decades—most famously in her novella-length profile of Jerry Falwell, one of the preeminent warlords in the Christian Right’s crusade for political power. Her massive accounts of the Vietnam War (Fire in the Lake) and the Cold War (Way Out There in the Blue) have been praised for FitzGerald’s ability to wed the “inner histories” of complex political events, as the historian Alan Brinkley put it, with their cultural contexts. The promise of this similarly vast, new history—all 752 pages of it—lies in its subtitle: The Struggle to Shape America. Here, it suggests, is a book that will speak to our times.

But despite its size, the scope of FitzGerald’s history is oddly narrow. Like many historians, she sees the 1980s as the moment when the Christian Right “reintroduced” religion into politics—a focus that makes it difficult to persuasively connect recent events, like the rise of Trump, with the long and extraordinary history of compromises and shifting allegiances among evangelicals. For her, Trump’s victory reflects the waning power of the Christian Right’s leaders more than the actual priorities of millions of evangelical voters. Her story follows a single path through evangelical history, from the big men of the Great Awakening to the big men of today’s Southern Baptist Convention. As a survey of the political inclinations of evangelical white male leaders, The Evangelicals is a valuable book, but it leaves out too many other people to yield much insight into the state of American politics, much less the varieties of evangelical experience. A tradition rooted in a belief in a personal Jesus and an intimate—if sometimes terrifying—divine can’t be defined by its pulpits alone. To understand “the evangelicals,” even just within the context of politics, means exploring what it feels like not just to preach, but also to sit in the pews. It requires us to examine evangelical Christianity as a religion lived by people who are also concerned with race and class, art and music, fear and ambition.

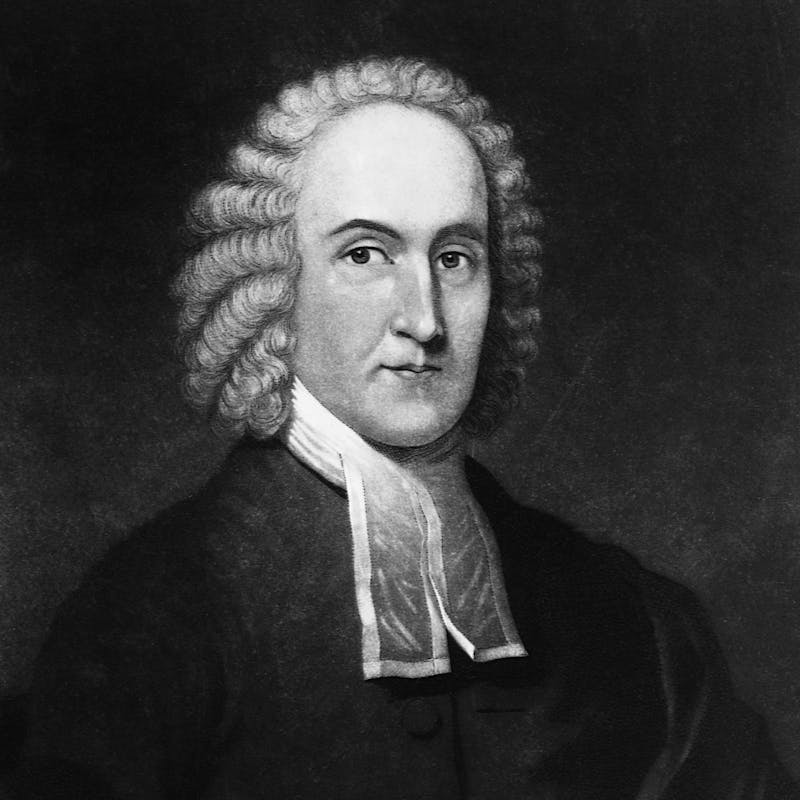

FitzGerald begins her history in the 1730s, with the First Great Awakening—the revival that did much to give American evangelicalism its intertwined public fervor and personal intensity—and its most notable figure, Jonathan Edwards. The Evangelicals devotes only two pages to this most central of early figures, and FitzGerald spends them mostly on the “vivid rhetoric” of his “most quoted sermon, ‘Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.’” Preached in 1741, “Sinners” is vivid in its blistering account of human unworthiness, its description of “the God that holds you over the Pit of Hell, much as one holds a Spider, or some loathsome Insect, over the Fire, abhors you, and is dreadfully provoked.” Edwards, writes FitzGerald, was “telling people what they already believed.”

Yet by focusing on the ferocity of his sermons, FitzGerald understates the influence of Edwards, one of the most learned men of his day. He was responsible for turns both bold and subtle in American Protestant thought, imbuing its blend of sentiment and “heart” with a kind of empiricism of the supernatural. Still taught in Christian academies and studied by pastors, Edwards is channeled in ways obvious and implicit into contemporary church life. His sense of storytelling can be seen in contemporary evangelicalism’s concern for “relevance,” a buzzword that animates churches large and small, with sermons that might pass muster on The Moth, and his sense that “science” served to create a godly community can be seen in science-flavored “messages” among evangelicals about “creation care” and “intelligent design.” These strands are essential in understanding how evangelicalism thrives in the twenty-first century as a broad faith—one not only of moral control, but also of curiosity about a world that so many evangelicals say they are “in but not of.”

In her sketches of early American Protestant evangelists, FitzGerald emphasizes two arguments uncontroversial in American religious history: the centrality of revival to early American life, particularly the ways in which it fostered a kind of raw democracy, and the winnowing down of Protestant intellectualism into “a simplified religious system well adapted to frontier communities.” For every Jonathan Edwards, there’s a George Whitefield, a revival preacher most famous not for his thought but for the loudness of his voice, or a Gilbert Tennent, who, called to arms by Whitefield’s bellow, launched an attack on milder clergymen. (He argued, as FitzGerald puts it, that only ministers who had “undergone a conversion experience”—rather than those whose calling was a matter of choice or intellectual attraction—“had the power to save souls.”) Then there’s Francis Asbury, who rode a 5,000-mile circuit each year during the early nineteenth century’s Second Great Awakening to make Methodism a major Christian current in America, and William Miller, who persuaded some 50,000 souls that the Bible foretold the end of the world in 1844. Many of his believers, disappointed to find themselves still among the living, went on to found the Seventh-Day Adventist Church.

Such men relied on fervent preaching that would inspire spiritual feeling in their listeners. By encouraging congregants to display those feelings publicly, they created a style of worship that, while deeply personal, would exert a strong influence on national politics. That’s particularly true in the life of Charles Grandison Finney, the best-known and most significant figure of the Second Great Awakening. FitzGerald offers a succinct account of Finney’s “new measures,” crowd-pleasing preaching innovations that anticipated the megachurches of the latter half of the twentieth century and laid the foundation for much of contemporary evangelicalism’s performativity. When someone in the congregation was “on the verge of conversion,” FitzGerald writes, Finney made them sit “on an ‘anxious bench’ in the front of the church, where the whole congregation could see them when they felt the spirit and stepped forward.”

Prayer and conversion thus became public, intensely social events, where men and women expressed their deepest feelings before a crowd. After people had humbly asked for mercy and watched many others do the same, they found a new sense of trust in one another. Family ties were strengthened, enemies made up, and strangers found a sense of community.

Out of this “spiritual democracy” sprang much of what would become the abolitionist movement. This early history, widely known within evangelical circles, if not beyond, is essential to understanding the sense of righteousness that continues to propel evangelical politics, even in its embrace of a man such as Trump. He might be a sinner, but so, too, was Finney before he was saved; and so, too, was the biblical David, even after God made him king. God uses who he will to achieve his virtuous ends, and it is the job of the believer to follow, not to lead.

There was, of course, plenty of self-interest within the church in Finney’s day, just as there is in ours. Finney’s works were made possible by major American financiers, who saw in his religion not just righteousness but also an answer to the labor troubles of the era, when workers were responding to industrialization with the angry stirrings that would give rise to the labor movement. It’s too simple to say that Finney urged them to wait for their pie in the sky, but not by much. Like many moral leaders, Finney was both a friend to the poor and an enemy to their efforts at self-organization.

Such antecedents help explain the continued closeness between evangelical politics and moneyed interests. Just as merchants funded Finney, big oilmen backed the National Association of Evangelicals and Billy Graham in the 1950s. They were bound together by what Max Weber famously described as The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, a kind of theological myth of WASP thrift combined with a fear of atheist communism. Christian best-sellers of the last century glorified big business, from Bruce Barton’s 1925 book The Man Nobody Knows, which presented Jesus as a modern CEO and his apostles as his executives, to Dennis W. Bakke’s 2005 self-help guide Joy at Work: A Revolutionary Approach to Fun on the Job, which urges faith in Jesus but not unions.

Students of American religious and business history increasingly emphasize how evangelicalism has served capitalism—a relationship touted by some believers as “biblical capitalism,” in which the “Protestant ethic” is whittled down to the conviction that scripture prophesies supply-side economics. Bethany Moreton’s To Serve God and Wal-Mart: The Making of Christian Free Enterprise and Kevin Kruse’s One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America are two recent works that explore the sincerity of such a seemingly self-serving faith and the ways in which “business conservatism” and “social conservatism” are not at odds so much as they are entwined strands of Christian nationalism.

But FitzGerald relies for her synthesis on a number of respected but increasingly dated sources. As I read, I began making a list of the dates of publication of her sources: 1957, 1967, 1966, 1975, 1962, 1977. More recent publications were much rarer, and many were from evangelical or conservative intellectuals. As FitzGerald uses them, these sources emphasize the formal theological and political decisions made by evangelical elites. What’s missing from her account are elements that might have complicated this familiar narrative—elements, in short, that might have helped readers understand how the evangelical surge for Trump, a philandering celebrity businessman, fits into the longer history FitzGerald tells.

That’s not all that’s missing. FitzGerald makes clear from the beginning her intention to write a history of white evangelical politics, but is there really any such thing as a white American history without black history? Can we speak of evangelicalism, slavery, and abolition without mentioning figures such as Sojourner Truth, or Maria W. Stewart, another black woman who, in 1831, just as Finney was coming to fame, published an influential abolitionist pamphlet titled “Religion and the Pure Principles of Morality”? In 1957, or even 1967, well-intentioned white historians evidently thought we could. But in 2017, with race at the heart of the politics that gave rise to Trump and what may well be the most fundamentalist cabinet in history, any account that seeks to place our religious past in “contemporary history,” as FitzGerald puts it, must make race central to its concerns.

Curiously, FitzGerald skips the Civil War, a conflict in which religion provided a powerful undercurrent to the more visible crises of race and region. And in her account of the years that followed, she considers class more closely than race. Fundamentalism, she shows, emerged not, as Marx and cliché would have it, as the consoling religion of the poor, but as a faith of ambition for those less concerned with Christ’s Sermon on the Mount than with the theological currents that decades later became known as the “prosperity gospel.” Dwight L. Moody—a nineteenth-century revivalist who preached to crowds of tens of thousands—appealed not to “the wretched factory laborers,” FitzGerald writes, “but to people much like his younger self: rural-born Americans with Protestant backgrounds who were making their way in the cities in white-collar jobs.” Evangelicalism is nothing if not aspirational in its theology. If its explicit commitments once hewed to that of an “old-time religion,” its aesthetic has always been shaped by a keen sense of the new, the fresh, and the modern—terms which can be read, in America at least, as euphemisms for the middle class.

Partly because of this class anxiety, efforts to lump evangelicals into the very voting bloc the political class now describes were not so simple. In 1942, a group of evangelicals formed the National Association of Evangelicals, hoping to escape the label “fundamentalist,” which had gained low-class connotations as rural and uneducated, even though in its origins it was an urban and intellectual phenomenon. “The term ‘evangelical’ didn’t mean very much,” FitzGerald observes, “because liberals also regarded themselves as evangelicals, [and] fundamentalists used the terms ‘fundamentalist’ and ‘evangelical’ interchangeably.” The NAE, for that matter, defined itself in fundamentalist terms. Created to oppose “the terrible octopus of liberalism,” the group wanted political influence, but its elite leadership had not been very effective at directing, via its many member denominations and their many pastors, the hearts and minds of the evangelicals in their pews—not to mention the evangelicals who sat in pews beyond the organization’s reach.

The best-known evangelist of the twentieth century, Billy Graham, was more effective than most at influencing large swaths of evangelicals. Born on a farm in North Carolina in 1918, he combined evangelical class anxiety with fundamentalist theological certainty, the myth of the country boy with the reality of the Washington sophisticate. Graham was a synthesizer. Among his many gifts was an ability to build coalitions—between fundamentalists and evangelicals, between urban and rural conservatives and moderates. But while he jettisoned the fundamentalist emphasis on separatism that would have obstructed the growth of his influence, the faith he made was ever the “old-time religion,” which was really a modern creation, a synthesis itself of theology, nationalism, and capitalism as authentically old-fashioned as Cracker Barrel’s front-porch rocking chairs.

FitzGerald, however, mostly hews to the school of thought that sees Graham as somehow more moderate than the Christian Right that emerged in the late 1970s. Graham, she insists, “wasn’t a racist.” As evidence, she quotes his banal statement in 1950 that “all men are created equal under God.” But while Graham integrated his revivals, he also believed that Martin Luther King Jr. had gone too far with the civil rights movement and should have “put on the brakes a bit.” That duality—a sincere denial of racism, accompanied by its thinly euphemized perpetuation—is essential to the Christian Right politics that thrived after Graham withdrew from politics in the 1980s, and forms the evangelical backbone of Trumpism today.

The political formation known by news magazines as the “Christian Right”—the lifespan of which occupies as much space in FitzGerald’s book as the previous 200 years combined—might be fairly said to have emerged in the ’70s or ’80s. FitzGerald, following the conventional wisdom of American political history, calls it a “reintroduction.” And yet the very evidence of her book, as well as much recent scholarship, suggests that the “Christian Right” was more of a revolution in branding, coinciding with regional realignments of the Democratic and Republican parties, than it was, as FitzGerald puts it, an “eruption.” Evangelicalism had been engaged in conservative political action since the last major rebranding in 1942, which emerged from the embrace of the term “evangelicalism” over “fundamentalism.” Still, it’s here that The Evangelicals is at its strongest and most detailed, relying on the excellent reporting that FitzGerald did in the 1980s and ’90s. But it’s also where her work is at its weakest: Exceptional as her reporting was in its day, it remains embedded in the logic of its moment, mistaking the sensation of a strident new generation of evangelical political leaders for an authentically new development.

FitzGerald describes, for instance, televangelist Pat Robertson as a figure “who didn’t fit any of the old categories,” even as she neglects the fact that Robertson’s father, a right-wing Democratic senator, had long led attempts to push evangelical values in national politics. A board member of a fundamentalist organization known as International Christian Leadership, the elder Robertson met with President Harry Truman in 1947 to ask him to attend the organization’s meetings, comprised almost exclusively of political, business, and military leaders. Truman didn’t take him up on the offer, in part because the Moral Re-Armament movement already provided him with a similarly powerful network. Six years later, though, International Christian Leadership bagged its first president when Billy Graham and Senator Frank Carlson persuaded a newly elected President Dwight Eisenhower to attend the first occasion of what became known as the National Prayer Breakfast. Just one year after that, as President Trump noted at this year’s Prayer Breakfast, Carlson and other members of Congress sent Eisenhower a joint resolution that added “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance. (“It’s a great thing,” Trump added.)

Conservative evangelicalism has been an essential part of American politics going back much further than 1980. International Christian Leadership was the Christian Coalition of its day, less visible mainly because its aesthetic was establishmentarian. By contrast, Robertson and his peers, following the example of Reagan, emphasized the populist aesthetic of their tradition—even as they encouraged their followers to cling ever more fiercely to the corporate economics that had once been more of a concern of the men who paid for revivals than for the men and women who attended them.

What did change with the rise of the Christian Right was its emphasis on the politics of the body. Not so much actual bodies as imagined ones: particularly those destroyed by what some evangelicals came to call the “holocaust” of abortion. Towards the end of The Evangelicals, FitzGerald pays special attention to the case of Terri Schiavo, whose brain-dead body became a cause célèbre for evangelicals in the 2000s. The why of this turn toward the body—beyond the past interventions of fundamentalist intellectuals like Francis Schaeffer and Chuck Colson—remains an important question in evangelical history. FitzGerald would certainly be excused for failing to come to any strong conclusions. But she explores neither the significance of Schiavo’s fate in the lives of believers, nor the ways in which, for evangelical leaders, it was as much a stylistic change as a substantive one, a substitution of one jeremiad of cultural collapse for another.

Before its current obsession with the body, as FitzGerald observes, evangelicalism expressed itself politically through extreme and often paranoid anti-communism. My favorite example is the 1958 horror film The Blob, which told of a carnivorous mass of red Jello. Conceived at the Presidential Prayer Breakfast in 1957 by Shorty Yeaworth, an evangelical filmmaker, the movie was widely viewed as either pure kitsch or an anti-communist metaphor free of religious overtones. American evangelicalism before the 1980s was no less political in its theology; its theology just happened to align with the anti-communist beliefs of the secular sphere.

Today, the political expression of evangelicalism seems strongest in its opposition to Islam. In this sense, it may be aligning, once again, with widely held secular anxieties. During last year’s campaign, evangelical elites confidently assured FitzGerald and other journalists that evangelicals would not back Trump, even as the rank and file roared its support for him at his huge rallies, many of which opened with sermons. Millions voted for Trump because, like Mike Pompeo, Trump’s pick to head the CIA, they see Islam not as a world religion but as America’s enemy number one—a threat “not just in places like Libya and Syria and Iraq,” as Pompeo has said, “but in places like Coldwater, Kansas, and small towns throughout America.” Evangelicals also voted for Trump because of what religion scholar Jason Bivins calls the “politics of horror in conservative evangelicalism”—a theological strain that predisposed them to support a candidate who could portray the current low ebb in the national crime rate as nothing short of “American carnage.” Others gravitated to Trump because, after half a century of the prosperity gospel, they saw his gold-crusted campaign as evidence of God’s blessing.

Such is the complexity of evangelicalism in the pews—a spiritual tradition deeply intertwined with American ambitions and American fears. If FitzGerald misses the deeper historical undercurrents of evangelicalism, it is in no small part because the leaders she focuses on—the white men in the pulpit—are equally blind to the lives and beliefs of those who worship in their churches. The preachers of religious conservatism would be wise to remember their own sermons. We are, as evangelical leaders are fond of observing, a revival nation. Which is another way of saying that in America no politics—or maybe just no theology—ever truly dies.