My grandfather owns a t-shirt that reads, “Whoever has the most things when he dies, wins.” I’ve been thinking about that phrase ever since I came across Norm Diamond’s photos of estate sales, where a recently deceased person’s belongings are sold over the course of a few days through a firm, which takes a cut of the proceeds. Diamond’s photos of peoples’ stuff are haunting and intimate, and they support the idea that the things we accumulate during our time on Earth can in some way define us in death.

Diamond never met any of the hundreds of men and women whose homes he scoured for more than a year in his native Dallas. But looking at their their unusual collections and personal mementos in his book What Is Left Behind, which Daylight Books will publish in May, one can’t help but feel a connection with them — and then, inevitably, a sense of loss.

In another life, Diamond worked as an interventional radiologist at Dallas’ Baylor Medical Center for more than 30 years. There, he became acquainted with people under similarly grim circumstances—when they were in the grips of a medical emergency, or near death. Until retiring and seriously taking up photography in 2012, he said, he’d suppressed the kind of emotions that should have accompanied such encounters—he had to, in order to preserve his professionalism and well-being. Going to estate sales helped him process those decades of accumulated grief, he said, and it made him confront life’s impermanence in a whole new way. “Your mortality hits you like a Louisville Slugger,” he says.

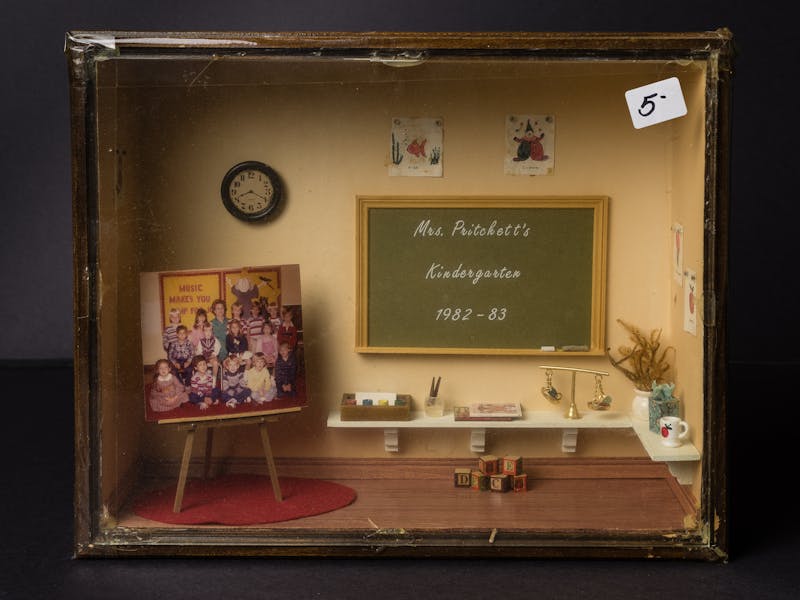

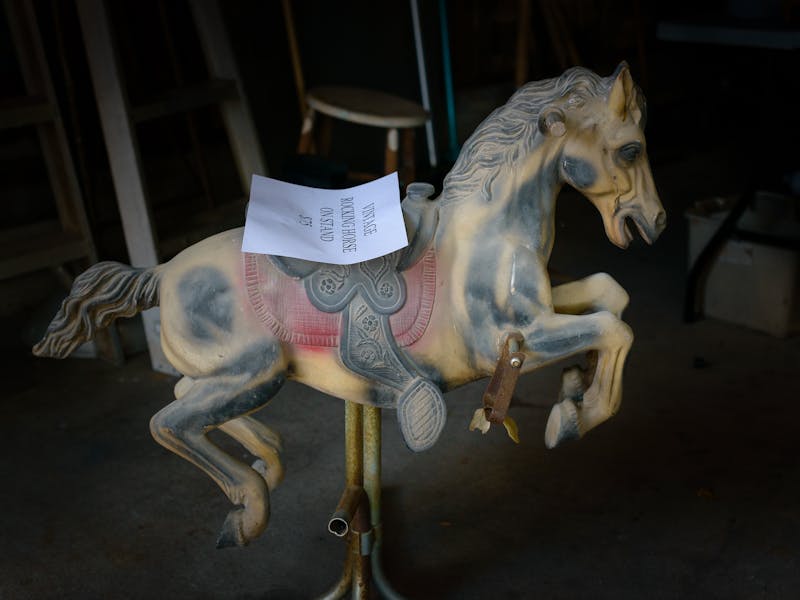

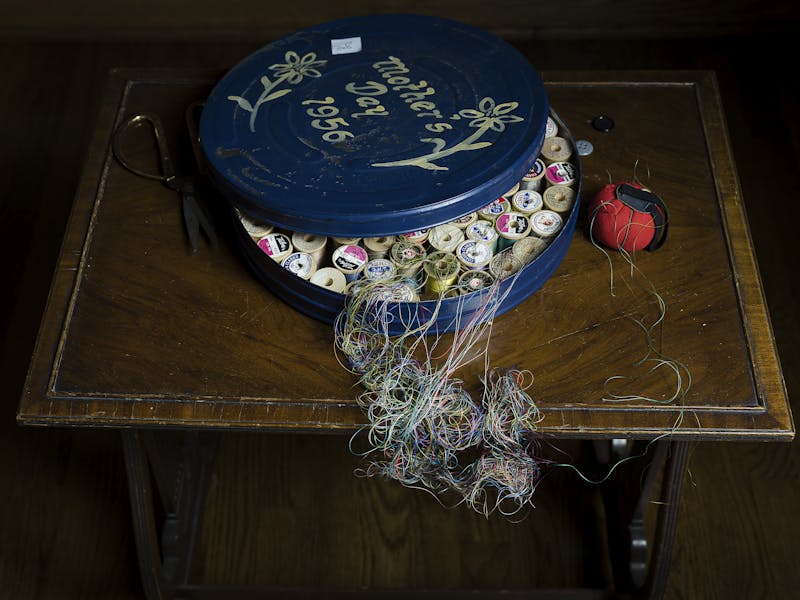

At the sales, Diamond looked for objects that communicated something about their owner’s life. Often, the belongings left over when a person died were testaments to loss, long illnesses, or the kind of poverty that conditions people to hold on to things, just in case they come in handy one day. Other times, what was left over was more sentimental. He saw a closet filled with Stetsons and bottles of Old Spice, a wig stored inside a box made for caramels, birth announcements for three children born between 1909 and 1913. Some days, he photographed those items as he found them. Other days, he bought items—always under $25— that caught his eye, and photographed them at his home in better light. He still has boxes of the stuff.

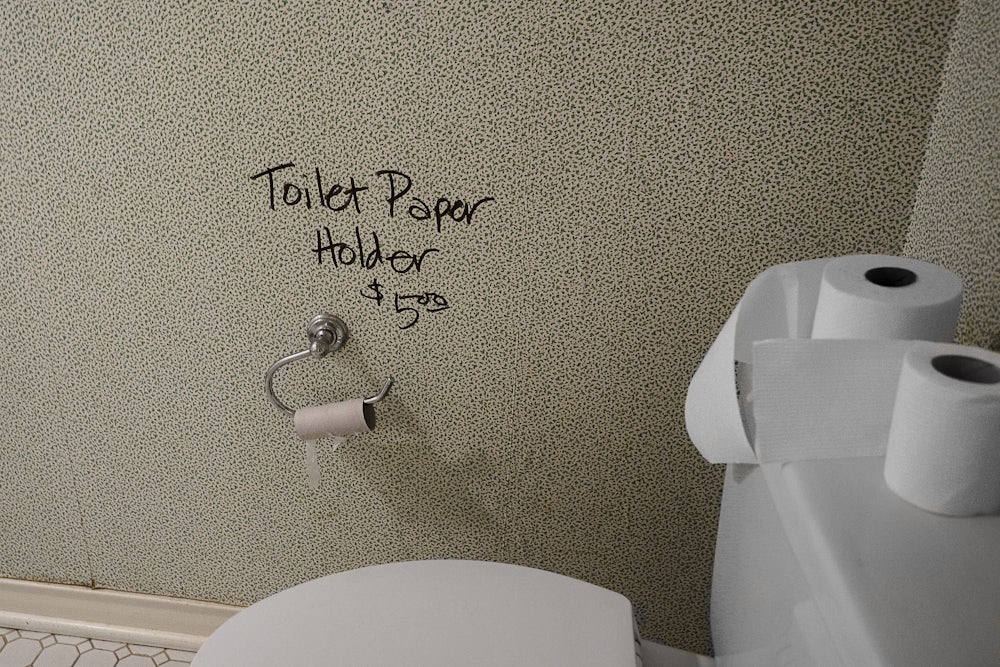

Diamond was also looking for moments that highlighted the dark humor of estate sales. One photo shows signs that warn prospective shoppers, “You break it you bought it” and “All sales are final.” The overwhelming sense is of the absurdity of consumption: Even if you can afford to buy everything you want, you’re still going to die one day. In one picture, a toilet paper holder, with a depleted cardboard roll still dangling off it, with its price written on the wall in Sharpie. Diamond’s title for the image? Everything Must Go.

“Amongst my colleagues at the hospital, we loved to laugh. We saw humor whenever we could find it. I looked for humor in the sales as well,” he said.

Other photos seem to point to the absurdity of life itself. In one, the image of a man dressed to impress in a white diner jacket and black bow tie looks out from a frame on a bedside table. His back is straight and his chin is up: It’s a photo of someone expressing his own self-worth. On his lapel, a neon green sticker pronounces the cost of the photo: $2.50.

It’s possible to look at Diamond’s pictures and despair. How disposable our lives seem, you might think, once all the things we’ve worked hard to create and acquire are priced and sold to the next guy. But there’s also something liberating in this perspective. Things, in the end, don’t make winners or losers, and they don’t save us from death. But they do tell stories about how we’ve lived.