Amazon has long ceased to simply be “Earth’s Biggest Bookstore,” which was how it described itself back when it launched in 1994. It’s now the Everything Store, a place where you can buy underwear and bananas. It is the largest e-retailer in the world, accounting for more than half of all e-commerce growth in 2016. But that does not mean that books have ceased to be important to Amazon—and it certainly does not mean that Amazon, which dominates the book industry in the United States, has ceased to be important to publishers. That’s why a recent tweak in the way Amazon sells books has publishers and authors very worried.

For all outward appearances, the relationship between Amazon and the publishing industry had settled into a wary peace, following a highly publicized dust-up in 2014 between Amazon and Hachette, wherein Amazon tried to bully Hachette in negotiations over e-book prices. But tensions had been quietly ratcheting up since then. While some of Amazon’s advances against the publishing industry have gained headlines, many of its most damaging moves have received little coverage outside publishing trade publications.

The most recent strike by Amazon was made public late last week in a HuffPost article written by author and independent publisher Brooke Warner, who revealed a new Amazon program that allows third-party re-sellers to “win” the buy button on book pages. (This program has existed for a while on Amazon, but books had previously been exempted.) If you were looking for a book and Amazon was out of stock—or, perhaps, was charging a higher price for a new copy than a third-party seller—you would automatically be prompted, via Amazon’s patented one-click system, to buy from a third party.

To qualify, third-party sellers have to sell new books and meet certain criteria involving price, availability, and delivery time. The rub is that these third-party sellers have not always purchased books from publishers—they sometimes are selling remainders or advance copies. Publishers—including some very, very large ones like Penguin Random House—are now desperately figuring out the sources of these sellers’ books. They are worried that publishers and authors may not be paid from all sales.

This may seem like a small thing, and so far it seems to be affecting only a small percentage of books. But it has the potential to be an earthshaking change for some publishers, and is being seen as evidence that Amazon is willing to elevate third-party sellers to further erode publishers’ bargaining power and market share.

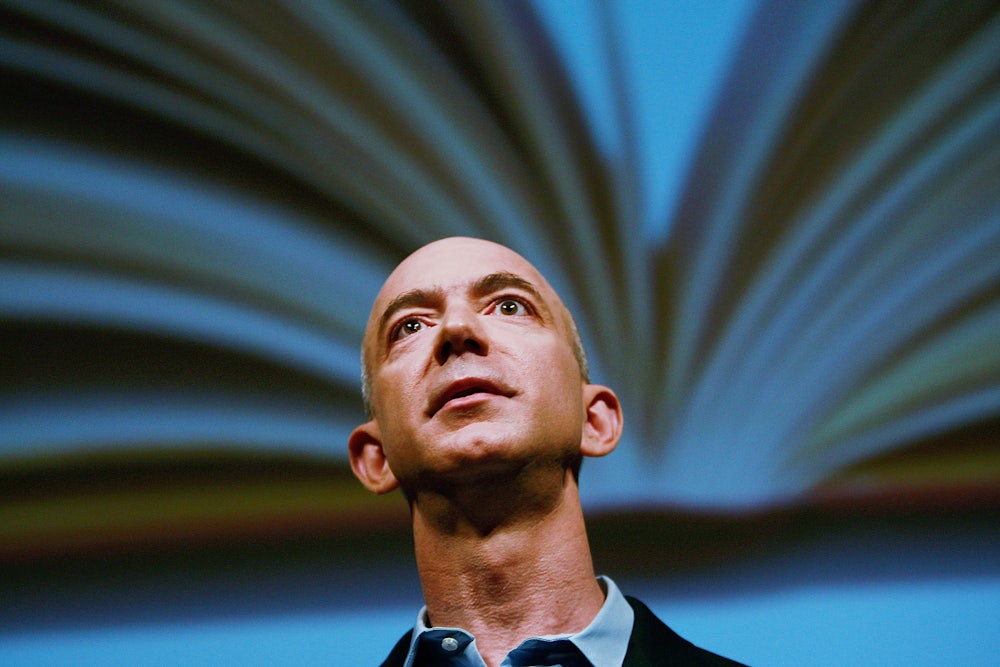

Amazon first introduced third-party sellers back in 2000. Then, the company was striving to rapidly expand its business, and allowing established businesses to enter the fold was a way to accomplish that. “We wanted to position ourselves as the place to start for shopping,” Amazon executive Diego Piacentini told The Los Angeles Times in 2004. This created a virtuous cycle for Amazon, or “flywheel,” one of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos’s favorite terms. As Brad Stone wrote in The Everything Store:

Lower prices led to more customer visits. More customers increased the volume of sales and attracted more commission-paying third-party sellers to the site. That allowed Amazon to get more out of fixed costs like fulfillment centers and the servers needed to run the website. This greater efficiency then enabled it to lower prices further. Feed any piece of this flywheel, they reasoned, and it should accelerate the loop.

Third-party sellers have been integral to Amazon’s growth, and Amazon has used that growth to squeeze suppliers. Publishers have long grumbled about the markets for both used books and remainders and saw Amazon’s embrace of third-party sellers as an existential threat. In 2000, shortly after the third-party marketplace launched, the Authors Guild and the Association of American Publishers teamed up to condemn Amazon’s thriving online market for used books. “If your aggressive promotion of used book sales becomes popular among Amazon’s customers, this service will cut significantly into sales of new titles, directly harming authors and publishers,” they wrote in an open letter to Bezos.

In the 15 years since, the Authors Guild, which represents the interests of working writers, has remained one of Amazon’s most vocal critics. After the news that Amazon had begun allowing third-party sellers to “win” the buy button, it strongly condemned the company. “Without a fair and open publishing marketplace, publishers will soon lose the ability to invest in the books that advance our knowledge and culture,” it said in a statement.

Amazon, for its part, argued that there was nothing to see here: “We have listed and sold books, both new and used, from third-party sellers for many years. The recent changes allow sellers of new books to be the ‘featured offer’ on a book’s detail page, which means that our bookstore now works like the rest of Amazon, where third-party sellers compete with Amazon for the sale of new items. Only offers for new books are eligible to be featured.”

While publishers often play the part of Chicken Little in this dispute, there is real reason for alarm. Amazon has long wanted to have its cake and eat it too—to be the Everything Store, but not to invest heavily in warehousing space. Its physical footprint has expanded exponentially recently, but so has its sales—and its stock. Amazon doesn’t want to keep lots of dead stock on hand, so passing that burden to third-party sellers, which either provide their own warehousing or pay Amazon for the privilege, makes sense.

Similarly, a number of publishers have said that Amazon is taking less stock upfront from publishers. This reduces what it’s holding as stock, but also leads to Amazon frequently running out of stock of items, particularly unexpected hot sellers. Kicking the buy button to a third-party seller in such situations prevents the book from showing up as being “out of stock.”

Many publishers believe they’re being cheated by sellers in the third-party marketplace, which don’t acquire their books from official channels—instead they sell remaindered copies (books that did not sell in stores and were returned to the publisher) or “hurts” (books with minor blemishes), often for rock-bottom prices. If these books are “remainders” or “hurts” or pirated, as some publishers have claimed they are, then publishers and authors won’t see a dime.

It’s unclear how Amazon vets its third-party sellers to make sure the items they’re selling as “new” were actually purchased from the supplier. But Amazon did inform Publishers Marketplace that it “remain[s] dedicated as always to removing bad actors,” and pointed suppliers to a form they could use if they believed a third-party seller was infringing on their rights.

It’s unlikely that the authors of perennial New York Times bestsellers would be affected by these changes. Amazon doesn’t want to alienate them, and has been pushing publishers to lean even more heavily into mega-selling hardcover books. Rather, it is midlist authors and independent publishers that are most likely to feel the squeeze. With the demise of Borders and the decline of Barnes & Noble, backlist—i.e. paperback fiction and nonfiction more than a year old—has never been in a more precarious position. These modestly selling books—books that don’t justify warehouse expenditures—are most likely to be kicked to a third-party seller.

The fear is that there an even stronger focus could be put on frontlist hardcover sales—which are dominated by a mere handful of authors—which would further push out midlist authors. These are often the kinds of writers who are nominated for the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, and they would see their backlist sales, a crucial piece of income, decline further. Taking backlist income away from publishers and authors could also hasten the decline of the trade paperback, a medium that Amazon dislikes because it’s not as lucrative.

Finally, there’s the possibility that this is a ploy to create another revenue stream. The Authors Guild says that several publishing sources have surmised that “Amazon is attempting to coerce publishers into using its print-on-demand (POD) services.” Amazon’s thinking is that, if a book were to unexpectedly go out of stock, then it could be printed immediately, essentially solving the whole stock problem. (POD, Amazon has argued, would also increase delivery times.)

Publishers see this as a slippery slope. Book publishers’ entire business model is based on advance sales—on retailers buying books in bulk from the publisher and then selling them to consumers. Switching to a POD model would disrupt a supply chain that has existed for decades. More importantly, it would also essentially make Amazon the printer for much of the industry’s stock, giving the retailer even more clout—and allowing it to extract more money from publishers.

Seen in this light, this change to the buy button could work as leverage for Amazon in negotiations—let us print books on demand, the company could say, and we’ll make sure the buy button never goes to third-party sellers.

Publishers and authors are rightfully concerned that these changes will take money out of their pockets. The biggest worry is what impact it could have on America’s literary culture. “The connection that people fail to make,” Authors Guild President Mary Rasenberger told me, “is that if publishers have less money, then they have less to invest. That means they can’t afford to take risks on the kinds of challenging books they’ve published for centuries.”