An airplane is the perfect, and perhaps the only, place to actually read Monocle, the globe-trotting lifestyle magazine founded in 2007 by Tyler Brûlé, a Canadian editor and erstwhile war correspondent. Its logo, an “M” with a twisted loop inscribed in a circle, lurks at airport terminal bookstores all over the world, the magazine’s glossy black cover—which the late David Carr likened to “a slab of printed dark Belgian chocolate”—conveying a placeless, easily translated sort of luxury. Inside, one encounters articles on Canadian soft power, Latin American soap operas, and Finnish domestic architecture: the casual reading of an armchair diplomat.

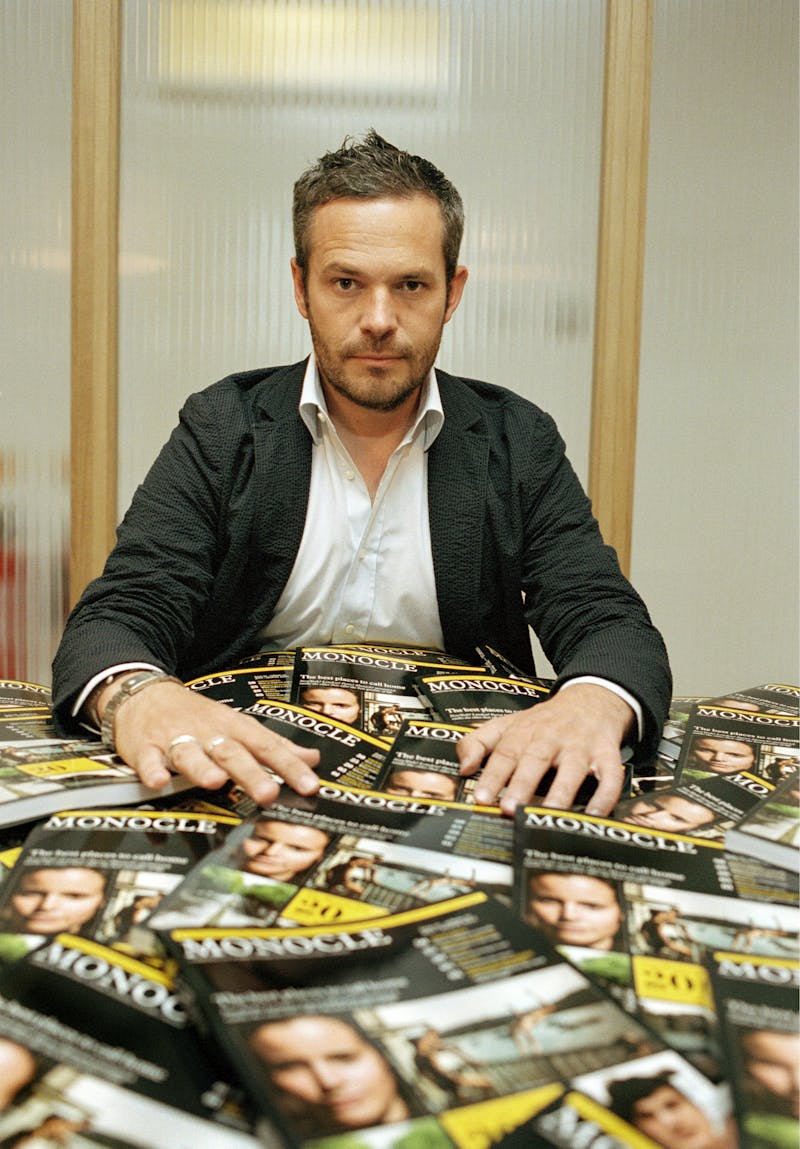

Over the years, Monocle has become as much a status symbol as reading material. Its editor is one of the world’s foremost lifestyle auteurs, a tastemaker of late capitalism and “a Martha Stewart for the global elite,” per New York magazine. Brûlé has promoted his personal version of the good life via high-profile columns in T magazine and, more recently, the Financial Times, where he reflects on travel etiquette and philosophizes about “relaxation” for the one percent. Monocle’s tote bags, which come with the $130 annual ten-issue subscription price, mark an itinerant tribe of 80,000 who may identify more with the magazine than with the country on their passports.

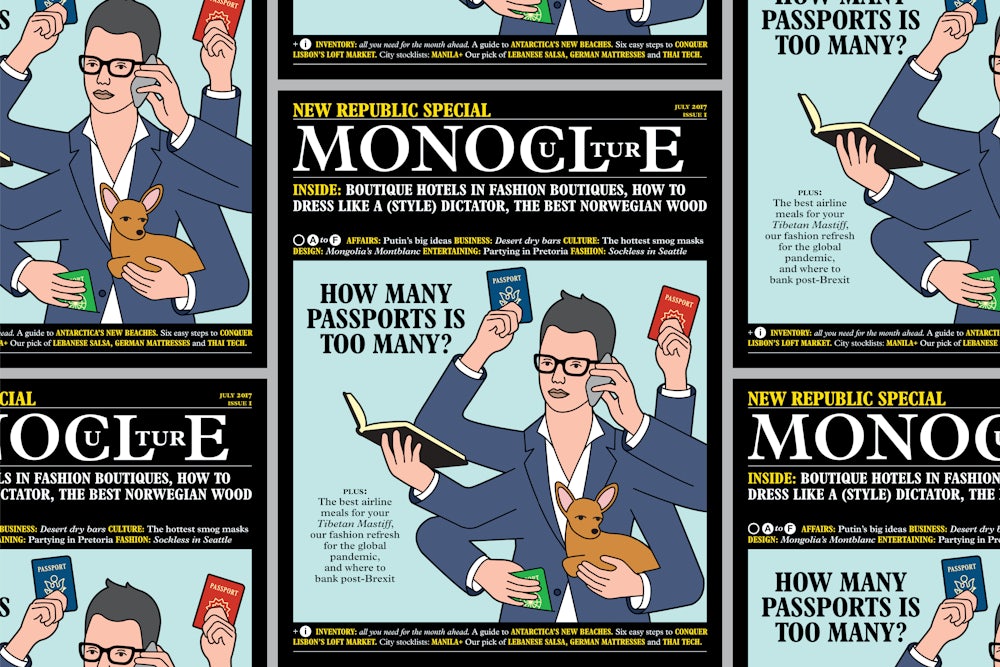

As older titles like GQ, Vanity Fair, and The Economist lose their grip on millennials, the Monocle Man—spot him by his sharp suit that ends at bare ankles, glasses with prominent frames, and wide, unbuttoned collar, just like Brûlé himself—is alive and well. In 2014, Nikkei, the Japanese media conglomerate, bought a minority share in Monocle at a purported valuation of $115 million. Although the company is private and doesn’t release metrics, it has only grown since then, launching new publications and opening several retail spaces. The editors celebrated their 101st issue this March with an understated redesign. You can’t overhaul a classic, so not much has changed: The header logo is a little bigger and the layouts less cluttered. It’s more of a victory lap than a pivot.

While Monocle projects confidence in the march of globalization, it barely hints at the growing threats to the world of open borders and free-flowing capital it depicts. The magazine’s globalist chic contrasts sharply with the nationalist movements in the United States and Europe seeking to limit immigration, including visa programs for the skilled workers in tech and finance who might read Monocle. Yet the publication shares with the right a faith in free-market economics; Brûlé himself is less a citizen of the world than a shopper in its gigantic, globalized mall. His magazine, which built its brand by identifying the world’s hippest (and most profitable) trends, feels increasingly out of touch.

Jayson Tyler Brûlé’s long, careful path to world domination began in rural Winnipeg, where he was born in 1968 to a Canadian football player father and an artist mother. His parents, rumor has it, did not include accents over their last name. In interviews, Brûlé likes to say that his international sensibility formed during his childhood, inspired perhaps by his mother, an Estonian immigrant. News and decorating magazines were plentiful in the homes the family passed through in Ottawa, Montreal, and Toronto, as was Danish furniture. Aspiration came early. When he was 14, Brûlé cleaned yachts for a summer job and bought a Rolex with the proceeds.

Idolizing his fellow Canadian, the ABC news presenter Peter Jennings, Brûlé aspired to be an anchorman himself, and in his early twenties worked in London for the BBC. He reported freelance from Afghanistan for several years, and in March 1994 he was shot twice in a sniper attack, leaving him with little use of his left hand. While recuperating from surgery back in London, he read home decor and cooking magazines and contemplated, as we all must, how to live. In 1996, Brûlé took out a small-business loan to launch Wallpaper, a design and lifestyle magazine. Its polished photo shoots and furniture-as-fashion aesthetic paved the way for commercially and critically successful publications such as Dwell and Apartamento.

Brûlé’s description of the ideal audience for Wallpaper is often quoted: “I call them global nomads,” he told The New York Times in 1998, before the term had become a technology-inflected cliché. “Whether they’re a West Coast snowboarder, a copy writer for a hot advertising firm in Stockholm, or a grunge kid working in an indie record shop that suddenly got a film deal, there’s a degree of affluence all of a sudden.” In other words, bohemians made good who could suddenly spend a lot of money, anywhere, fast. They were a new archetype, with taste, capital, and mobility in equal measure. The magazine’s hopeful globalism, meanwhile, fit with the end-of-history triumphalism that permeated the late ’90s, in the wake of the Cold War but before September 11.

The concept was a hit. In 1997, after only four issues, TimeWarner acquired Wallpaper for $1.6 million. Brûlé was all of 29 years old. He stayed on as editor in chief until 2002, when, chafing at corporate leadership, he left. (Another version of the story says that he and TimeWarner clashed over his habit of indulging in “private helicopter rides.”) Having signed a noncompete that prevented him from starting another magazine, Brûlé launched Winkreative, an advertising agency for clients that might have bought pages in Wallpaper: tourism boards, airlines, and luxury condo developments.

After his noncompete expired, Brûlé assembled a few wealthy investors for Monocle, “a briefing on global affairs, business, culture & design,” according to its cover slogan for the first hundred issues. In some ways, the timing did not seem opportune: The first issue appeared in February 2007—on the eve of the financial crisis, and at the start of a sharp decline in the fortunes of print media. But Monocle performed a crucial function for the wealthy and those who market to them: Its content provided the global elite with a fresh definition of luxury and a renewed sense of confidence in the material rewards of the economic system that had just failed. A recurring column in the magazine analyzes a world leader’s personal style, and each year Monocle prints a Quality of Life Survey that suggests which city you might move to if you could move anywhere. (Tokyo was the 2016 winner. The same city also won in 2015. In 2014, it placed second.) Monocle gave its readers—and those who aspire to be like them—a way to define themselves and recognize each other, making Brûlé’s company an influential, if unlikely, force in publishing.

Monocle hasn’t just given globalized capitalism a hip aesthetic; it has also operated skillfully as a business in the many markets it both covers and covets. In the magazine, it’s next to impossible to discern what space is paid for as advertising and what is not. In the March 2017 redesign issue, for instance, there are “collaboration” ad packages with the nations of both Thailand and Portugal; each package appears next to unpaid Monocle editorial content about said countries. These are less evenhanded appraisals than buoyant travel guides to new resorts, museums, and shopping districts—the flows of creative capital, broadly speaking, that one might experience while doing business in such places.

This murkiness stems directly from Monocle’s business structure. Under an umbrella entity incorporated in Switzerland called Winkorp, Brûlé’s ad agency, Winkreative, sells creative services to companies that also often buy ads in Monocle. Both firms share a London headquarters that Brûlé, a Japanophile, has branded Midori House. The model is similar to that of the T Brand Studio at The New York Times, The Washington Post’s Brand Studio, and other recent in-house creative agencies developed by legacy media brands. Winkreative, which predates them by a decade, must inspire jealousy both for its financial success and for its weak business-editorial divide.

Brûlé has positioned himself at the head of a vertically integrated and ever-expanding media empire. On top of the Winkorp cake, he has added Monocle-branded clothing lines that can be bought through the magazine; hardcover books about home decoration and nation building; a 24/7 streaming radio station; retail stores around the world; and cafés in Tokyo and London that serve up a wan, placeless cuisine of Monocle chicken katsu sandwiches and Monocle taco salad bowls. The magazine is essentially a giant branding opportunity, an omnipresent advertisement for the true product: the Brûlé lifestyle.

It’s a way of life that has increasingly come under fire from political leaders. “If you believe you are a citizen of the world,” British Prime Minister Theresa May pronounced last year, “you are a citizen of nowhere.” May became prime minister in no small part because she argued that the people of her country couldn’t trust the Monocle class—not just the Eurocrats in Brussels, but also the global financial elite and PR gurus like her predecessor, David Cameron—who were too untethered to act in the best interests of the nation. The rise of May, the vote for Brexit, the election of Donald Trump—all represent a conscious renunciation of the globalist ideal that Monocle has helped to cultivate.

When Brûlé was recently asked about May’s observations on “citizens of nowhere,” he neither engaged with the discontents of globalization—the real-world worries over lost jobs and the erosion of local identity—nor did he make the case for his magazine’s brand of enlightened cosmopolitanism. He simply dismissed critics like May as “silly people.” “This is the way of the modern world,” Brûlé told the South China Morning Post. “It’s not just nationalism, it’s petty.” In other words, putting up barriers is more than a political mistake, it’s tasteless—a cardinal sin in the Monocle theology.

With the recent redesign, some glimmers of political reality are beginning to enter the magazine’s editorial voice. The new page layouts are more text-heavy, with longer articles and fewer glossy photos and twee spot illustrations. The content has a new seriousness, though it remains ever-optimistic. In an interview for the March issue, the CEO of Lufthansa says he is confident that globalization “cannot be stopped or slowed down, even though some people are trying hard.” The president of Portugal, adopting the vocabulary of a start-up founder, pitches his country as “a platform between cultures, civilizations, and seas.” (“We were an empire,” he reassures readers, “but not imperialistic.”)

Monocle views the world as a single, utopian marketplace, linked by digital technology and first-class air travel, bestridden by compelling brands and their executives. Diversity is part of the vision—the magazine’s subjects are from all over the world, and its fashion models come in every skin color—but this diversity is presented, in a vaguely colonialist way, more as a cool look to buy into than a tangible social ideal. Cities and countries are written up as commodities and investment opportunities rather than real places with intractable problems that require more than a subsidy to resolve. If London is too expensive, Brûlé proposes, why not found your next business in Lisbon, or Munich, or Belgrade? If you don’t, someone else will, and you might just get priced out again.

The magazine doesn’t idealize homogeneity of race or gender norms, but rather a global sameness of taste and aspiration. Every Monocle reader, regardless of where they live or work, should want the same things and seek them out wherever they go in the world, forming an identity made up not of places or people but of desirable products: German newspapers, Thai beach festivals, Norwegian television. The end result of this sameness is that a country can pitch itself to the monied Monocle class simply by adopting its chosen signifiers, or hiring Winkreative to do it for them in a rebranding campaign. In this way, the magazine warps the real world in its own editorial image.

A recent article in The Guardian about Lisbon described the city as embracing “Monocle urbanism,” a shorthand for all that the magazine glorifies: plentiful local culture, a relaxed pace of life, modernized airports, and co-working spaces. The new Lisbon resembles “a speeded-up east London,” as the city transforms from off-the-grid backwater to Airbnb-infested production hub of the international creative elite. Capital, and with it cultural capital, floods to the place where it can most efficiently reproduce itself, places that Monocle takes pains to identify and share. In 2015, in fact, the magazine hosted its very first Quality of Life Conference—in Lisbon.

It’s as easy to be charmed by Monocle as it is to hate it. Who doesn’t like a good Japanese leather origami bag? But if nationalists have a point in decrying the “global citizenship” that Monocle epitomizes, it lies in the magazine’s subtle approach to cultural homogenization. Brûlé’s stylistic vision has reproduced itself to the point of banality: Whether due to his own efforts or to the changing tide of taste, Danish furniture, clean cafés, shared offices, and artisanal food and clothing can now be found everywhere, attracting a floating tribe of international consumers the way flowers attract bees. The magazine’s worst offense may be that it is boring.

Now that Monocle has helped make the global lifestyle so ubiquitous, giving it up is hard, even if you don’t believe in it. British Home Secretary Amber Rudd wants to implement “barista visas” post-Brexit, to enable Europeans to work in U.K. bars and coffee shops for two years, without claim to housing or other benefits. The Brexiteers want strong borders, but not at the expense of their daily flat whites—which are, in fact, an Australian innovation. Mobility to travel, consume, and work is a luxury primarily available to the wealthy; the poor and disenfranchised find themselves blocked on every front. Refugees and asylum seekers don’t number among Brûlé’s “global nomads,” nor do itinerant workers who can only travel at the mercy of ever more stringent visa regulations.

The challenge confronting globalization is not, in the end, one of individual style. It is one of inclusion and independence. Is it possible to form a truly global community without sacrificing local identity and self-determination? While the vision formulated by Monocle may have been profitable, it no longer looks plausible. In the first century A.D., the Roman philosopher Seneca wrote, “One should live by this motto: I was not born to one little corner—this whole world is my country.” Today, to the satisfaction and benefit of Monocle’s globe-trotting readership, the whole world may indeed be our country. But we’re still deciding what kind of country it is, and whether Brûlé’s target audience will be the ones who ultimately control it.