If a government’s finances, as economist Joseph Schumpeter once wrote, strip away rhetoric to lay bare the true “spirit” of a people, then President Donald Trump’s first full budget proposal reveals a nation that is bombastic and fearful, grandiose and uncertain. Regardless of what actually makes it through Congress, the suggested cuts—$616 billion from health insurance for the poor, $140 billion from student loans, more than $190 billion from food stamps—outline a vision of government based on the notion that the state should stand aside so businessmen can work their magic. “This budget’s defining ambition,” the preamble states, “is to unleash the dreams of the American people.”

As remarkable as the scale of the cuts is the way Trump justifies them: the fear of debt. His budget message is threaded with dire warnings about our “unsustainable” national debt, which is nearing $20 trillion. This mounting burden, he warns, will place the United States in “uncharted fiscal territory,” leaving it vulnerable to “fiscal and economic crises.” The country has “borrowed from our children and their future for too long, the devastating consequences of which cannot be overstated.” To stave off a crisis, we must tighten our collective belts—which means cutting virtually every program designed to aid the most needy and marginal among us.

Trump’s invocation of debt as a justification for austerity is oddly evocative of the fiscal crisis that gripped New York City more than 40 years ago, a moment that seems to have shaped his thinking deeply. In the early 1970s, back when young Donald was busy running the outer-borough apartments his father had built, the city had fallen on hard times. A recession, white flight, and the loss of industry were making it tough for the city to pay for its impressive array of social services, including public hospitals and libraries, cheap mass transit, and a citywide university system. In the spring of 1975, when banks refused to continue marketing the city’s debt, New York turned to the federal government for aid. But the city was stonewalled by the administration of Gerald Ford, who counted among his advisers Alan Greenspan (fresh from the circles of Ayn Rand) and Donald Rumsfeld.

For these rising conservative stars, New York’s debt crisis was an opportunity to teach the country a lesson about fiscal responsibility. The possible risks of bankruptcy—for the city, state, even the federal government—seemed less important than bringing New York to heel. The administration’s disregard for the dangers of default led to the famous Daily News headline, “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD.” (The paper recently revived the line when Trump withdrew from the Paris accord as “TRUMP TO WORLD: DROP DEAD.”)

Ford eventually consented to provide the city with short-term federal loans—but only if it agreed to downsize. New York was forced to slash more than one-fifth of all municipal jobs, through steep cuts to police, fire, sanitation, and schools. It closed several hospitals, along with many clinics. In the spring of 1976, after the City University of New York ran out of funds and had to shut down before exams were completed, the system began to charge tuition for the first time. Ford and his conservative acolytes had succeeded in forcing the city to renegotiate the social contract.

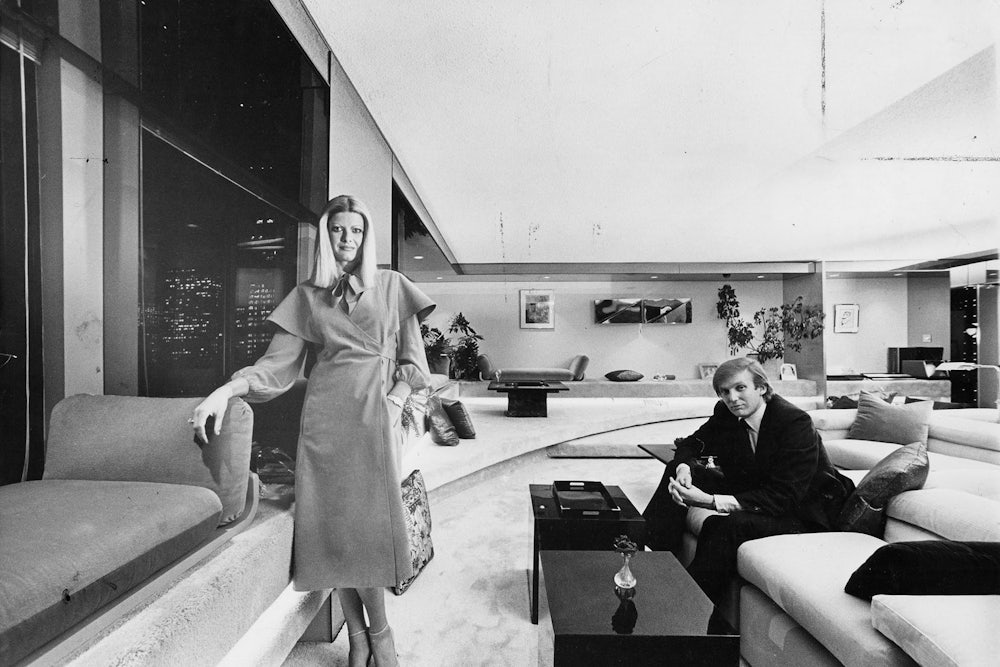

But while the poor and middle class of New York City were suffering, some people got richer—including Donald Trump. To make up the budget shortfall, city officials redoubled their efforts to woo developers and big corporations. In one of their first marquee efforts, they extended a major tax break to Trump to redevelop the decrepit Commodore Hotel near Grand Central Terminal, working with the Hyatt Corporation. It was the youthful developer’s first sally into the world of Manhattan real estate. As of last fall, Trump and Hyatt had saved more than $350 million in property taxes on the hotel.

What began in New York has now spread far beyond the five boroughs. Thanks to years of tax cuts, revenue-strapped cities and states across the country are being forced to slash wages for public employees, privatize emergency services, close libraries and other public institutions, and reconsider pension obligations to teachers, firefighters, and police officers. At the federal level, the massive tax cuts enacted under George W. Bush—and allowed to stand by Barack Obama—have ballooned the debt and left the government scrambling to pay its bills. That’s why it’s deeply hypocritical of Trump to use the rising debt to justify slashing aid for the poor. Far from “unleashing” America’s economic growth, his budget proposal includes more tax cuts for the rich—a move that will only worsen any crisis. Indeed, according to Bloomberg News, wealthy Americans are deferring their tax payments in anticipation of future cuts to come.

Despite Trump’s dire warnings, an actual debt crisis is unlikely: Congress has raised the debt ceiling 14 times since 2001. But whether or not a crisis materializes, the president is happy to use the specter of public debt to inflict even deeper cuts to public services. It’s a lesson he learned firsthand in his hometown during the 1970s: Hard times afford the perfect opportunity to force through an ever more constricted vision of government—one in which health care, schools, and food stamps matter less than tax cuts for developers to build shiny, glass-wrapped hotels.