Jon Ossoff is losing! Oh, never mind, he’s winning! Actually, just give up and go home—or donate now, and take advantage of a special matching offer!

Subtract Ossoff’s name, and you could be forgiven for thinking this is a pitch from the Home Shopping Network, rather than emails produced by a congressional campaign. They reflect old marketing tactics—blitz your audience, mislead them if necessary—and they are divisive. Proponents insist that the emails, as deranged as they might seem, work. Critics argue that the tactic has a short shelf life and is deceptive.

And in an era when email has become a crucial tool in reaching voters and raising money, they raise a broader question: Is this the best way for the Democratic Party to rebuild itself?

No special election in 2017 attracted the party’s interest like Ossoff’s race against Karen Handel to represent Georgia’s Sixth Congressional District. Democrats wanted not only a much-needed seat in the House of Representatives, but a pretty scalp: It’s Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price’s old district, and President Donald Trump barely won it last November. Ossoff’s strong showing in the first round of voting encouraged the DCCC to spend nearly $5 million on his campaign.

With Mothership Strategies consulting, the campaign launched a frenetic email fundraising drive that contributed to the race becoming the most expensive in the history of the House. Mothership was founded by DCCC veterans, and the online fundraising strategy it helped the Ossoff campaign develop is a descendant of the DCCC’s infamous 2014 strategy, which the Daily Beast described as “part fundraising pitch, part hostage note.”

The Ossoff emails warned of electoral doomsday. The subject lines often contradicted emails that had been sent earlier that day. As election day neared, the pace increased. The campaign bombarded its email list with increasingly desperate pleas for money—or psychological intervention, depending on your interpretation.

I love Jon Ossoff but i wish his campaign emails weren't written by a suicidal ex-girlfriend pic.twitter.com/GLDkHtgjf6

— Jim Mickle (@Mickle_Jim) June 4, 2017

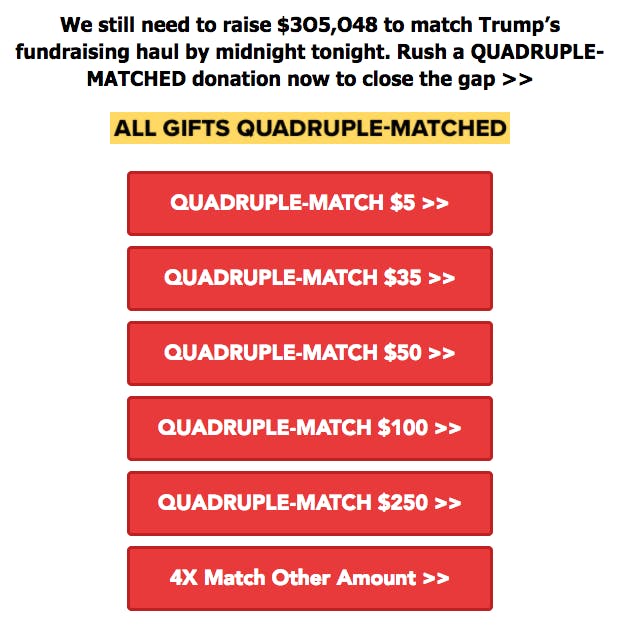

Kenneth Pennington, the former digital director of Senator Bernie Sanders’s presidential campaign, calls this a “churn and burn” approach that exploits voters. “A dirty secret in the email fundraising industry is that most of the people giving are senior citizens,” he told the New Republic in an email. “For a less net-savvy generation some of these emails that put you on ‘FINAL NOTICE’ are confusing and scary enough. The prospect that your donation will be quadruple-matched may also be enticing, if you really believe it.”

Pennington also believes the DCCC approach achieves short-term results at the expense of long-term strategic goals. “There’s a limited pool of Democratic small-dollar donors out there,” he said. “When the Ossoff campaign and DCCC run a churn-and-burn program like this, it sullies the pond for every other Democratic cause. When people get turned off by fundraising emails, they tune out. Not just from the bad programs, but from the good ones. Everyone from Elizabeth Warren to UNICEF is going to feel that.”

I love @ossoff but the 20 emails a day with clickbaity subjects begging for donations are so unbelievably annoying. pic.twitter.com/niEBCqi7Il

— Zach Berger (@theZachBerger) June 8, 2017

Michael Whitney, formerly Sanders’s digital fundraising manager, called the DCCC strategy a “wildly deceptive, unrelenting approach that treats supporters like garbage.”

“I think about email fundraising in two ways,” he explained. “The first is that of the DCCC and Mothership and several others, which focuses on a brutal math centered on short term return on investment.” The other, he says, is the approach of the Sanders campaign, which not only generated enormous amounts of money, but also fostered genuine voter engagement. “When you are level with somebody, and show their power and what’s possible when people take collective action, they will respond,” he said.

But there’s no denying that the churn-and-burn strategy gets results. Ossoff did raise a lot of money. His fundraising helped him remain competitive with Handel, who benefited from her own massive out-of-state network. Until a future Congress resurrects serious campaign finance reform, Democrats must stay afloat in a system rigged to defeat them.

Furthermore, consultants don’t all agree about the dangers of the churn-and-burn approach. Mothership Strategies would not go on the record for this story, and neither would a representative of the Ossoff campaign. But Stephanie Grasmick Sager, a partner with Rising Tide Interactive, told the New Republic, “We don’t worry about presidential campaigns ruining TV because they run nonstop commercials in October. So it doesn’t makes sense to suggest that campaigns are ruining email by ramping up volume when engagement is the highest.” (The DCCC is one of Rising Tide’s clients, though it does not work on the DCCC’s email strategy.)

Sanders’s email fundraising strategy also suggests an alternative approach to content and tone. As Clare Foran noted in The Atlantic last year, the Sanders campaign sent long, detailed emails that ran “anywhere from 1,000 to 2,000 words” to supporters. Those emails were not free of hyperbole; in February 2016 the campaign had to correct misleading information about the price of a ticket to an expensive Hillary Clinton fundraiser. Nevertheless, the campaign’s overall strategy marked a stark departure from conventional wisdom.

And it appears to have worked. Sanders raised $218 million online, turning a septuagenarian socialist into what HuffPost called “the greatest online fundraiser in political history.” His fundraising results are proof that Democrats need not be bound to a hysterical and possibly unethical approach. There are other, more substantive messages that can persuade voters to become donors.

Ossoff’s fundraising also benefited from the Trump factor, which would have energized liberal voters regardless of the campaign’s email strategy, and the uniquely high-profile nature of his race. It’s difficult to know, then, exactly how useful the DCCC/Mothership strategy really is. Ossoff outraised Handel, and he still lost to her by nearly four points. Facing a similarly Republican electorate in South Carolina, Democrat Archie Parnell lost his special election by a similar margin—after raising $763,000, in contrast to the $23.6 million raised by Ossoff.

The DCCC’s approach to email outreach is raising money, but is it building a vote-getting movement? Ossoff’s campaign shows the former does not necessarily lead to the latter. And if Whitney and Pennington are correct, and the DCCC is sacrificing long-term gains for short-term results, it’s fair to question the wisdom of a strategy that is more gimmick than substance.

The contrast between the Sanders and Ossoff approaches is not about left vs. center. (Mothership also worked on the campaign of Montana Democrat Rob Quist, who ran to Ossoff’s left.) But these strategic differences are ideological in a much broader sense: If the Democratic Party is going to cast itself as the opposition party, how should it conduct itself with voters? If the Democrats are to be the party of the people, in contrast to the GOP as the party of the one percent, it should consider treating voters less like sentient pocketbooks and more like partners in a political movement. The latter approach would still require the party to raise money, but in a way that doesn’t manipulate and deceive voters.

And that means the party’s relationship with its consultant class will have to change. Amidst the wreckage of Ossoff’s campaign there emerges only one winner: Mothership Strategies, which reportedly earned $3.9 million for its work. Everyone else—voters, the party, the candidate Mothership promoted—lost.

“I apologize all over the country for the volume of email people get, but it works,” then-DCCC chair Steve Israel told reporters in 2014. “Five million dollars in August. Five million dollars!” But fundraising didn’t prevent the party from being swept out of power. Money, while helpful, can’t buy you a movement.