As little as President Donald Trump understands about health policy, and as comfortable as he is peddling nonsense, there is one sense in which he has been more clear-eyed and forthright about the GOP health care repeal effort than most Republicans on Capitol Hill.

Trump likes to claim, without reference to the bills working their way through Congress or to any specific priorities of his own, that he wants to sign a health care law that has “heart.” But in an aside at a rally in Iowa last week, Trump gave explicit shape to this euphemism by telling the audience, “I said, ‘Add some money to it.’ A plan with heart.” He, unlike Republican congressional leaders, essentially acknowledges that taking money out of health insurance subsidies is heartless, and the way to achieve a plan with heart is to put some of that money back in.

There is now a faction of Republican senators that would like to save the Obamacare repeal push by doing exactly this.

“We are going to figure out a way, I believe, before Friday comes to greatly enhance the ability of lower income citizens to buy insurance on the exchange and at the same time my sense is that the 3.8 percent [investment tax cut] is going to go away,” Tennessee Senator Bob Corker told reporters on Wednesday. “It’s not an acceptable proposition to have a bill that increases the burden on lower-income citizens and lessens the burden on wealthy citizens.”

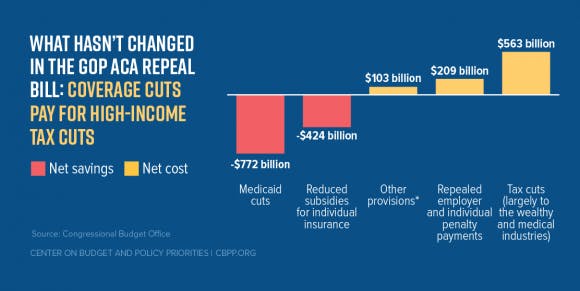

It is helpful that Corker dispensed with his party’s Orwellian pretenses about moving the medical system toward “patient-centered care” or “rescuing” the public from Obamacare, and described Trumpcare for what it is: essentially a zero-sum transfer of resources from poor and working class people (in the form of health care subsidies) to the wealthy (in the form of tax cuts).

This may end up benefiting Republicans in the long run, if it awakens them to the fact that nothing is impelling them to repeal all of Obamacare’s taxes and fill the budget hole with millions of people’s health care dollars. It has always been the case that Republicans could finance these tax cuts with higher deficits, or leave the taxes in place but ply the Affordable Care Act’s expenditures into different forms of government assistance. Linking them as Republicans have was a choice, and it is the reason their health care repeal push is constantly faltering and astonishingly unpopular.

But in the short term, Corker’s position complicates matters for the likes of House Speaker Paul Ryan, whose highest priority is enacting regressive tax cuts and second-highest priority is gutting welfare programs, because it concedes that millions of Americans will lose health insurance under the GOP plan. That raises an uncomfortable moral question: How many millions, exactly, do the Republicans think they can get away with?

Corker may be the first Republican senator to acknowledge that organizing a health care bill around the principle of trading broad-based subsidies for tax cuts would inevitably lead to massive coverage loss. His proposed solution is to limit the number of people who will lose health insurance by cutting taxes less. But it’s a solution that makes the political problem worse in some ways, because it’s terribly incomplete. By abandoning the all-or-none proposition of a choice between Trumpcare and Obamacare, it places Republicans in the unenviable position of pinpointing just how many people should lose health care to finance specific tax cuts for the affluent. Corker has established what Republicans are; now they’re just haggling over price.

Obamacare’s 3.8 percent investment income tax isn’t insubstantial. According to the Joint Committee on Taxation, repealing it would cost $172 billion in revenue over 10 years. But held up against the scale of the tax and transfer cuts in the Senate GOP health care bill, it just wouldn’t do enough to change Trumpcare’s brutal arithmetic.

Plying the savings from preserving the investment tax back into Medicaid and premium subsidies would shrink the red bars on the left and the orange bar on the far right, but not by enough to mask or alter or justify the basic theory of the bill. Many millions will still lose health care to finance huge business and millionaire tax cuts.

If it’s unjust, as Corker said, to increase the burden on lower-income citizens to give investors $172 billion over 10 years, why is it just to increase the burden on lower-income citizens to give health insurance providers a $145 billion tax cut? Or high earners a $59 billion cut on their Medicare taxes? Why are any of the 21 tax cuts in the Senate health care bill more important than letting ordinary people keep their insurance?

As The Washington Post’s Greg Sargent observed, Republicans were indulging some magical thinking if they imagined they could tinker around the edges of the House health care framework and not end up leaving tens of millions of people uninsured. But the arguments for doing Trumpcare halfway aren’t much cleaner, and in a way, a concession like Corker’s makes the moral proposition harder to obscure. My hunch is that the health care fight ends with all of Obamacare’s taxes wiped out in gruesome fashion—with members like Corker bought off with “bribe[s]”–or with essentially none of the taxes wiped out, or with a horse trade that delinks taxes and spending.

There are provisions within the Senate health care bill which, taken by themselves, would stabilize the ACA marketplaces. Pair those with some tax cuts, and “Trumpcare” would be transformed from the most hated bill in living memory into a sensible, modest deal that locks in coverage for millions of people’. The Senate could probably pass a bill like that with 60 votes, outside the budget process, so the tax cuts would be permanent. And nobody would have to address the unanswerable question Corker has raised of why uninsuring 22 million people would be morally unacceptable, but 16 million people would be perfectly fine.