Circa 1985, a pretentious young teenager in Cambridge, Massachusetts, I painstakingly typed out, on a typewriter, the lyrics to a song by an obscure English punk band—“Outdoor Miner,” from Wire’s 1978 album Chairs Missing—and push-pinned the words to my bedroom bulletin board:

No blind spots in the leopard’s eyes

Can only help to jeopardise

The lives of lambs, the shepherd cries

An outdoor life for a silverfish

Eternal dust less ticklish

Than the clean room, a houseguest’s wish

He lies on his side, is he trying to hide?

In fact it’s the earth, which he’s known since birth…

When I had transcribed and typed out the song’s lines, what had I produced? Why do we write out pop lyrics—on Genius or MetroLyrics, or in books like Bob Dylan’s The Lyrics: 1961-2012 or Nick Cave’s The Complete Lyrics 1978-2013—and when we do so, what relation does that text have to the recorded song?

One conventional answer would be to say that in turning the recording of “Outdoor Miner” into a written text, I had performed a radical reduction, even an act of interpretive violence. Wire’s lovely, enigmatic recording is a complex and fundamentally musical, aural creation, comprised of the singing of words, yes, but at least as importantly, of music: the guitar, bass, drums, piano, and voice, melody and rhythm, in their interrelation. To extract the words from this assemblage is akin to pulling out the bass line, or the drum track, and listening to that alone. Interesting as an experiment, perhaps, but false to the song in its totality.

Some would go even further than this critique, to suggest that in isolating and thus privileging the lyrics as a text, I was not simply violating the song’s integrity, or offering a piecemeal representation of it, but was performing an ideologically insidious act. Bookish student that I was, I was laying claim to a favorite band’s music as a form of literature, an austere modernist poem on the page; as respectable, intelligent, high culture, purged of its vulgar pop trappings.

It was once a truism that the presence of intelligent, “literate” lyrics was the major factor distinguishing quality pop music from disposable dross for teens. But recent years have seen a wide-scale rejection of the so-called “Rockist” pop-music aesthetic that favors singer-songwriter-based music, and its self-expressive lyrics, over other forms of pop. “To glorify only performers who write their own songs and play their own guitars” and to reject as shallow entertainers those who do neither, Kalefa Sanneh wrote in his influential 2004 New York Times article “The Rap Against Rockism,” is to overlook much of what is most vital in pop today (and, perhaps incidentally or perhaps not, to privilege a predominantly white tradition at the expense of African-American and other styles). The anti-Rockists or “poptimists” emphasized instead that performance, charisma, persona, sex appeal, and rhythm should all be considered at least as important as expressive language.

The awarding of the Nobel Prize for Literature to Bob Dylan this fall therefore produced a moment of ambivalence for many fans committed to the principle that pop must never be treated as primarily verbal. When the Swedish Academy’s Sara Danius told reporters that Dylan is “a great poet—a great poet in the English speaking tradition,” she was either declaring that pop music as a whole is a literary art, or that Dylan transcends pop music because of his distinctly literary qualities. Either claim is anathema to the poptimist.

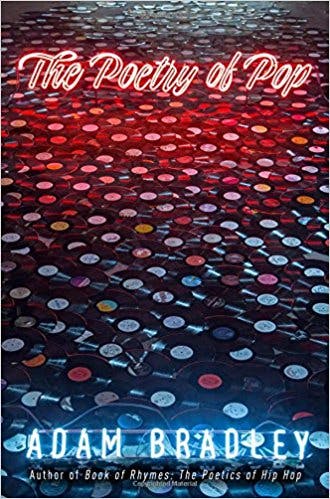

I’ve been convinced enough by the anti-Rockists that I opened Adam Bradley’s The Poetry of Pop with some skepticism, fearing it would make an English professor’s dated argument for the high-cultural cred of well-crafted lyrics. And when I encountered several pages of syllable-counting poetic scansion of Taylor Swift’s “Bad Blood”—“Did you have to do this?/ I was thinkin’ that you could be trusted”—I almost tossed the book aside:

Beginning with a simple syllable count, the song’s two verses establish an alternating pattern of a short line of six syllables followed by a long line of nine or ten syllables. The same pattern holds for the number of stressed syllables per line, which alternates between two stresses in the short lines and three in the long.

An extended close reading of the metrical variations of a Taylor Swift recording can seem, at first blush, like the most wrong-headed form of pop criticism imaginable: one that isolates the song’s language, abstracting it not only from music but from vocal expression, and that privileges the (surely fairly unremarkable?) words of the song at the expense of everything that actually makes us want to hear it more than once. Who listens to Taylor Swift for the syllable count?

Bradley—author of the previous Book of Rhymes: The Poetics of Hip-Hop and a former Ph.D. student of Helen Vendler at Harvard—is certainly that guy. But The Poetry of Pop makes a persuasive case, one that sidesteps many of the old debates over the literary value of pop. First of all, Bradley is not interested in establishing a restricted canon of the greatest pop lyricists. In the 1950s, structuralist critic Roman Jakobson famously defined what he called the “poetic function” of language—revealed in utterances in which the language itself, or the signifier, is prioritized over the meaning—as operating as forcefully in advertising or political slogans as in literature. (“I Like Ike” was a key example.) Bradley, like Jakobson, both sees poetic effects everywhere, and also believes that in certain forms of verbal expression, especially poetry, advertising, and songwriting, language users intensify and draw special attention to them.

Bradley is less interested in defining certain songwriters as poets than in opening our ears to the “poetic function” in pop songwriting generally: “It is invigorating to be able to trace the connections between the four-beat lines of Beowulf and the four-beat lines of Biggie, not because it ennobles one or debases the other, but because it reaffirms continuity across lyric creation.” And Bradley sees such effects not only in the complex wordplay or metaphors of an Elvis Costello or a Biggie Smalls, but in less showy or “literary” effects in songs by the likes of Guns ‘n’ Roses, Michael Jackson, or Rihanna: “Accepting a broader definition of ‘poetry’ or ‘poetic’ means including aesthetics that privilege qualities other than semantic difficulty.” (Bradley is excellent on the satisfactions of competent and even formulaic—rather than innovative or imaginative—pop lyrics.)

Nevertheless Bradley wants to make a case for the value of writing pop lyrics down. “A faithful transcription,” he reasons, “is a celebration of the songwriting craft.” By transcribing song lyrics into what he calls “lyrics at rest” on the page (as opposed to those “in motion” in performance), we can pay close attention to the effects of meter, rhythm, sound, and figurative language. We’re able to bring to the level of conscious understanding what we would otherwise likely only perceive subconsciously about how a song functions.

Perhaps Bradley’s most illuminating insight is his insistence that “the shape of the lyric,” the way it looks on the page, holds meaning and affects the way a song is performed. He argues, for example that when Van Morrison performs “Into the Mystic,” “his pushing and pulling at the syllables relies on them having an expected place in our minds, a place cemented by their poetic arrangements.” It’s partly on this basis that Bradley argues for the value of careful transcription and Vendlerian close analysis of lyrics: In order to appreciate and understand the liberties taken by a creative performer, one needs to grasp the norms that he or she violates. The words to “Into the Mystic” fall into four-beat lines of iambic trimeter, with some subtle variations:

We were born before the wind

Also younger than the sun

Ere the bonnie boat was won

As we sailed into the mystic.

“If the lyric were less soundly constructed and less rigorously patterned,” Morrison “would not enjoy the performative freedom that he does.” But this principle applies, too, with a less “creative” singer; sometimes the payoff of a given performance comes from a satisfyingly exact delivery of the rhythms and meters written into the lines, rather than from a departure from them. “Whether the performers outline or elide meter, its presence is defining.”

Returning now to my transcribed Wire lyrics, I see how they are thoroughly saturated by the poetic function. I mean that less as praise—though I do think they’re superb—than as a neutral description of language that so flagrantly emphasizes the play of the language itself over any signified meaning (though for what it’s worth, the song is about a species of fly called the leaf miner). Full rhymes, half rhymes and off rhymes proliferate, operating not only at the ends of lines—“leopard’s eyes”/“jeopardise,” “silverfish”/“ticklish”/“houseguest’s wish”— but in internal assonance and alliteration within and across lines: “the lives of lambs,” “lies”/“side/“hide,” “earth”/“birth.” And while iambic tetrameter, with four beats per line, seems to operate as the dominant meter of the song—“Can only help to jeopardise”, “Eternal dust less ticklish”—many of the lines offer variations on that meter, speeding it up or slowing it down, extending and compressing syllables, throwing stress to unexpected words and sounds. In the actual recorded performance, Wire’s vocalist Colin Newman makes subtle changes to the lines’ metrical patterning. But to grasp and understand what he does in performance, and how the song works, we need to grapple with the way the language operates “at rest,” as writing.

Bradley argues that there is “a small, special knowledge that songs reveal only to those who attend to their language temporarily removed from their performance.” I transcribed the lyrics to “Outdoor Miner” 30-odd years ago, The Poetry of Pop helped me to see, as a tribute and a gesture of love: as a way of honoring a brilliantly strange, joyful piece of writing (as well as a song), and of trying to figure out how it worked. It takes nothing away from the music to offer such an admittedly-partial tribute to the words.