In late 1772 Benjamin Franklin received a startling package from an unknown sender. It was a collection of letters from several high-ranking colonial officials in Massachusetts written to Thomas Whatley, an assistant to Britain’s prime minister. Their subject was the ongoing unrest caused by the Stamp Act, which imposed the first direct taxes on colonists, and by other legislation the people in Massachusetts judged oppressive and tyrannical. The officials reported that the colonists had started an insurrection: The king’s property was being vandalized and his officers harassed. Mobs controlled the streets, forcing British soldiers to seek safety on an island in Boston Harbor. Only a strong show of force, the officials insisted, would restore peace.

Franklin understood the significance of the documents. One of the authors was the royal governor, Thomas Hutchinson. Although he was Massachusetts-born, Hutchinson was hated by Boston radicals. His plan to protect his fellow colonists was to weaken representative institutions and strengthen the royal hand, including the use of British troops as police. “I never think of the measures necessary for the peace and good order of the colonies without pain,” he wrote. “There must be an abridgment of what are called English liberties.” More specifically, the republican constitution of Massachusetts must be carefully dismantled: “The government has been so long in the hands of the populace that it must come out of them by degrees.” Franklin knew how Massachusetts radicals like Samuel Adams would interpret these words: Their governor wished to deliver them into servitude. If the letters became public, they might lead to armed rebellion.

Considering his behavior up to this point—“Britain and her colonies should be considered as one whole,” he had written in the 1750s—Franklin’s next step appears baffling. From his diplomatic post in London, he sent the letters to the speaker of the Massachusetts Assembly, Thomas Cushing. The effect was predictably cataclysmic. Within the year, rebels were dumping the equivalent of millions of dollars of the East India Company’s tea into Boston Harbor. Within two years, British subjects began killing each other wholesale at the Battles of Lexington and Concord. The nearly two million British subjects living in the thirteen colonies had more individual liberty, more say in their government, more security, and more equitable taxation and administration of justice than any other large population in the world, perhaps in the history of the world. Franklin had put it all in danger.

One of Franklin’s most vocal critics was the royal governor of New Jersey—his own son. William Franklin had learned to be “a thorough government man” from his father, who was himself a government man until something happened in the early 1770s that prompted him take up the radicals’ cause. Until this time, Benjamin and William had been remarkably close: debate partners, scientific collaborators, business associates, and fellow servants of the Crown and colony. Now they would take different paths. One would become a rebel, a co-author of the Declaration of Independence, the new nation’s first ambassador to France, and a delegate to the Constitutional Convention. The other would become a leader of the Loyalists seeking to protect the honor of the British Empire and the safety of its subjects. They became, curiously, a radical father and conservative son.

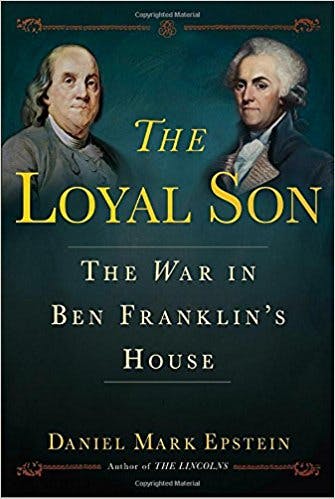

The Loyal Son is the first dual biography in over two decades, since Sheila L. Skemp’s Benjamin and William Franklin: Father and Son, Patriot and Loyalist. Epstein’s book is an elegant if slightly embellished narrative. (He has a habit, not unique to him, of adding details about things like weather and clothing that are not given in the sources he cites.) It is also a case study in a profound question about the revolutionary era. What caused Americans to choose one side or the other?

The story of the American Revolution is often told as a war between the colonists on one side and an invading force of Redcoats on the other, but this is misleading. The British military included thousands of American-born fighters. And, after the war, upward of 100,000 Americans went to enormous trouble to remain British. They left the new country for Canada, the Caribbean colonies, or the British Isles. The revolution was, as many of its participants called it, a civil war.

In Epstein’s hands, the case of Benjamin and William Franklin becomes superbly illuminating because he emphasizes how much they shared. Both were charming, industrious Philadelphia gentlemen. Both loved England, their English heritage, and King George. Both were men of the Enlightenment, knowledgeable in mathematics, science, technology, and the law. Both held advanced degrees from Oxford. Both were dedicated husbands, fathers, and public servants. Both had fathered a son before marriage and raised him as a legitimate heir. (The identity of William’s mother remains unknown even now.) And both fought bravely in the French and Indian War defending the British Empire. The side each took in the revolution cannot be explained by any obvious character trait or life experience.

While Epstein does not attempt to offer a comprehensive explanation of their choices, his narrative is suggestive and moving. When the moment of decision came in July 1776, Benjamin signed the Declaration of Independence, whereas William refused his father’s entreaties to join the rebel or, as Benjamin now called it, the “Patriot” cause. Crushingly, William’s son Temple sided with his grandfather. William was duly arrested by order of the Provincial Congress of New Jersey, a body which he reasonably considered treasonous and refused to recognize. William was jailed for two years before being released in a prisoner exchange. After a few years of work on behalf of the Loyalists in British-held New York City, he joined the thousands of Americans who emigrated to England, never to return to his homeland.

They saw each other only once more and were never reconciled. A few years before his death in 1790, Benjamin wrote to William:

Nothing has ever hurt me so much and affected me with such keen Sensations as to find myself deserted in my old Age by my only Son, and not only deserted, but to find him taking up Arms against me, in a Cause wherein my good Fame, Fortune, and Life were all at stake.

It hardly occurred to Benjamin that William might have held his own integrity in not being a traitor as something more valuable than his father’s wealth and reputation. Benjamin’s will mentions his son only to disinherit him, “leaving him no more of an Estate he endeavored to deprive me of.”

While William’s choices throughout the crisis seem consistent with his character and station, Benjamin’s case is more mysterious. Why did he, a servant of the Empire and father of the governor of New Jersey, send the letters to Cushing that quickly ignited a civil war? Some of his defenders say that he simply made a mistake. He misjudged the effect the letters would have when they reached Boston. Perhaps, as the editors of his papers say, “he was not thinking clearly.” This is a strange apology, however, because it implies that his later adoption of the Patriot cause was an act of face-saving. Having accidentally started the American Revolution he could not become a Loyalist. While people in positions of influence make mistakes under the crush of events, Franklin made fewer than most. It’s hard to believe that he would have committed such a transparent blunder.

At the time he received the letters, Franklin was living in London as a representative of Pennsylvania and Massachusetts seeking to mediate the differences between Britain and its colonies. Now in his mid-sixties, he was a giant of the British Empire with honorary doctorates from the universities of Oxford and St. Andrews, membership in the Royal Society (and a winner of its Copley Medal), and friendships with the great figures of the Enlightenment. After the publication of the letters, however, Franklin could no longer present himself as an honest broker and respectable civil servant. He seemed to take sides against his own government.

He earned the nickname “old Doubleface” and was called “the living emblem of iniquity.” The Privy Council summoned him for a humiliating cross-examination. For an hour, while Franklin stood silent, Britain’s solicitor-general thundered at him, charging him as a thief who had “forfeited all the respect of societies and of men.” “Into what companies,” the lawyer jibed, “will he hereafter go with an unembarrassed face?” After ten years of diplomatic work that now ended in disgrace, Franklin skulked home to Philadelphia, having missed his daughter’s marriage and his wife’s death during his time abroad.

His reputation at home also suffered. The Massachusetts radicals were far out of the main current of opinion. Most colonists held views closer to those of Governors Hutchinson and Franklin. While they resented the Stamp Act and other forms of direct taxation by Parliament, they were proud British subjects who saw a nearer danger in anarchy than in oppression. William argued that the crown’s presence was the only thing saving the colonies from chaos. Without it, he wrote, “The most despotic and worst of all tyrannies—the tyranny of the mob—must at length involve all in one common ruin.”

While we may never know why Benjamin sent the letters to Cushing, Epstein offers intriguing clues. Like many Americans of his time, Franklin believed that although the king had rightful authority over the colonies, Parliament did not because the colonists had no direct representation in that body. As far back as 1754, he had proposed a continent-wide Grand Council that would function in North America as a parallel to Parliament in Britain. By the time he mailed the fateful packet to Cushing, he had become convinced that the king lacked either the desire or the power to bring the plan to fruition. In 1770, Franklin wrote to a Boston pastor that he saw America sinking deeper under “the arbitrary power of a corrupt parliament, that does not like us, and conceives itself to have an interest in keeping us down and fleecing us.” If in the end, His Majesty George III, King of Great Britain and Ireland, would not put things right, Ben Franklin would.

Like George Washington, Franklin possessed a degree of self-confidence and physical courage that bordered on madness and that would have undone him many times over had he not been both supremely talented and one of the luckiest people of his age. Both he and Washington were nearly killed fighting in the French and Indian War. Each became wealthy through entrepreneurial ventures that bankrupted others. Each suffered catastrophic and humiliating setbacks that would have sent ordinary people into ashamed retirement, yet they climbed back to ever greater successes. And unlike Washington, who hardly ever stepped on board a ship, Franklin crossed the North Atlantic eight times in service of his career and his country, often in winter and often in wartime. I find it easy to believe that the man who went out in a storm with his son on a June night in 1752 to catch lightning from the sky, would have been comfortable setting the world ablaze in 1772 when a king refused to bend to his will. Franklin’s wagers usually paid off. The pen names under which he first became famous, Silence Dogood and Poor Richard, only highlight his history-altering genius and hubris.