On November 5, 1978, rioters put Tehran to the torch while the army stood by. “Not even a bloody nose,” the shah had instructed his generals from his home in the city’s northern hills, Niavaran Palace. Before the winter’s end, Muhammad Reza Pahlavi, the last in 2,500 years of shahs of Iran, would leave his throne for exile. Morose, melancholy and withdrawn, he barely resembled the resolute tyrant of Reza Baraheni’s Crowned Cannibals, the late 70s bestseller that depicted the shah’s rule as a period of macabre palace orgies and prisons brimming with dissident youth.

Baraheni’s book, fêted by America’s literati and reprinted in part by the New York Review of Books, contained many fabrications. The shah undoubtedly ran a repressive and undemocratic regime, but his vilification by human rights activists and the press in the seventies provided a new wave of revisionist historians with an easy foil. Andrew Scott Cooper in his first book, Oil Kings: How the U.S., Iran, and Saudi Arabia Changed the Balance of Power in the Middle East, linked the souring attitude toward Iran in the West with the shah’s insistence on maintaining high oil prices. In between, Cooper, seemingly, has succumbed to the charms of Iran’s last royal family. And no wonder: In an age of “Islamic terrorism,” the shah, a secular modernizer who spoke flawless French, appears sympathetic and comprehensible.

A former Human Rights Watch researcher, Cooper delights in refuting the “charnel house” image of the shah’s rule. The shah once balked at the New York Times’ comparison of him with Louis XIV. “I’m the leader of a revolution,” he replied, “the Bourbon was the very soul of reaction.” The monarch, who ruled absolutely, wished to be remembered as a liberalizer. Cooper complies—he points out the moment in 1977 when the shah threw open his jails to the Red Cross. Amnesty International had reported 25,000 to 100,000 political prisoners—the Red Cross ended up finding some 3,000. The shah’s human rights record was nowhere near as grim as Iran’s revolutionaries, or indeed President Jimmy Carter, believed.

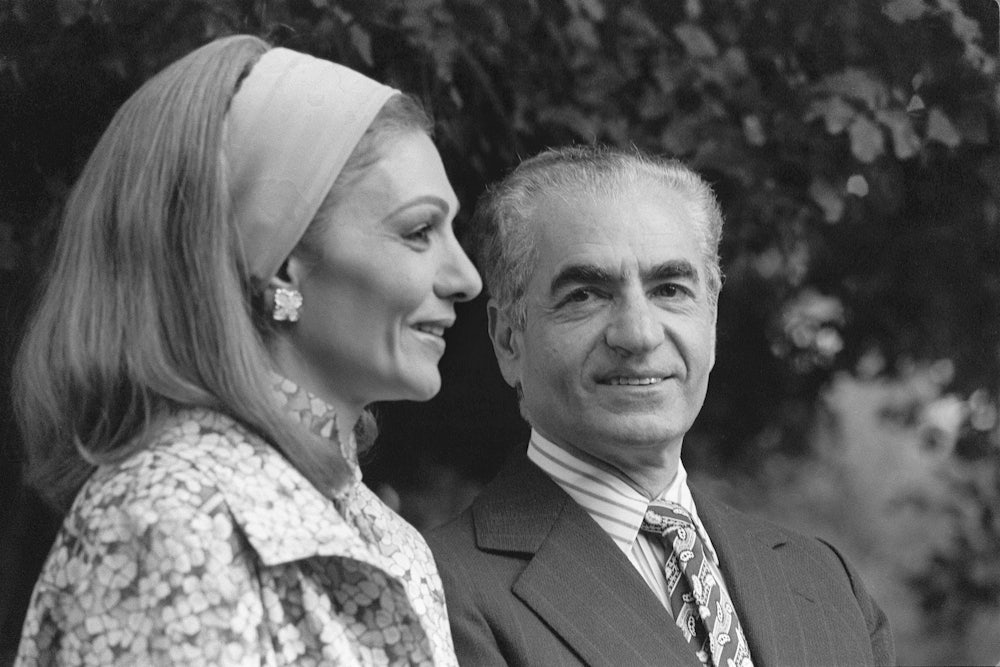

In The Fall of Heaven, his new book on the Pahlavi dynasty’s final days, Cooper attempts to portray Iran’s last monarch as a frustrated democrat, arguing that the shah’s liberalization program begun during the final years of his reign was ill-timed—right when American support for the shah, under pressure from human rights campaigners, wavered. Cooper cleverly moves the shah’s third wife, Farah Pahlavi, at once a Marie Antoinette figure and the saving grace of a corrupt regime, toward center stage of the royal pageant, always highlighting, but never overstating her role by the shah’s side.

On the afternoon of the riots, Cooper recounts, the U.S. ambassador Bill Sullivan, summoned by the shah for an audience, could find no-one, not even a footman amid the palace’s empty rooms, to lead him to the king. Iran’s Imperial Government was in disarray. At last, from a side door in the hall, out walked the queen, who was astonished to find Sullivan dawdling in the shadows. She led him to the shah, sequestered away in his private study. Unbeknownst to all but a handful of close associates and doctors, the shah was dying of cancer. Houchang Nahavandi, a regime insider, declares in his biography of the shah that the queen held a “de facto” regency in the final months. It is, doubtless, an exaggeration, but reflects the controversy about Farah Pahlavi and her circle, whose influence grew as the monarchy waned in 1978.

The following day, the shah appeared on national television. “I once again repeat my oath to the Iranian nation to undertake not to allow the past mistakes, unlawful acts, oppression and corruption to recur but to make up for them,” he said. “I have heard the revolutionary message of you the people.” It was an astonishing mea culpa. Had not the shah, after weeks of refusing, just appointed a military government of order? In private, he repudiated the speech (written by two of the queen’s aides). But there was little he could do. Within months, Pahlavi Iran, a showcase for Westernization, yielded to the Islamic state led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The ally, praised by President Carter the year before as an “island of stability” in a troubled region, turned into one of America’s staunchest foes. An era of Islamist revolutions across the Middle East had begun.

To all appearances in Washington, the shah—who had firmly led his country through two decades of social and economic progress—wasn’t going anywhere. In early August 1978, the CIA reassured the White House that Iran was not even in a “pre-revolutionary situation.” No one could imagine Iran without the shah. The Communists had been violently suppressed, the liberal opposition silenced, and the Islamists—well, the Shia clergy were powerful, but had they ever ruled?

Within a month of his audience with the shah, Sullivan fired off another report countenancing just that. It was titled: “Thinking the Unthinkable.” He foresaw a “Gandhi-like” position for Khomeini in the new Iran. While the White House hesitated over the suggested blueprint for action, Sullivan’s confidence in his own judgment and good intentions gently wreaked havoc on U.S. support for the shah. The ambassador’s rogue overtures to the Islamist opposition, including Khomeini, exiled in Paris, infuriated Carter, and contributed toward growing confusion over U.S. policy among palace officials.

Yet the shah was not a victim of history, as both Cooper’s book and the shah’s own memoirs, Answer to History, which he penned in exile, would suggest. The shah needed little help bringing about his own demise. “This country is lost because the shah cannot make up his mind,” an Iranian general told Sullivan. “You must know this and you must tell this to your government.” The king was neither able to accept the idea of reducing himself to a figurehead in a parliamentary government, nor of killing thousands to preserve his throne. He could not believe that Khomeini, whom he described as a “worn fanatic old man,” would overthrow him. His people were ungrateful.

The Fall of Heaven parses what went wrong in the 1970s, leaning heavily on the memoirs and testimony of regime loyalists, alive and dead. Cooper seems influenced by Asadollah Alam, the powerful minister of court who doubled as royal confidante, and wrote a close account of the shah’s rule, which he locked away in a Swiss bank. In his diaries, as at court, Alam was indefatigably shrewd: With an eye—one suspects—on posterity, he exonerated himself, heaping blame for the regime’s abuses on his rival the prime minister, Amir Abbas Hoveyda. The court minister bemoaned the government’s arrogance toward the mass of Iranians, and dared utter criticisms to his master—albeit wrapped in thick and courtly blandishments—when Hoveyda did not. “Pride comes before a fall,” he wrote about the shah’s hero, Charles De Gaulle, “though such absolute self-confidence is surely a sign of genius.” In his will, Alam stipulated his diaries be published when the Pahlavis no longer ruled Iran. He died a year before the revolution.

The feeling has long existed in royalist circles that had the shah allowed critical voices at court, he might have been less perplexed by the sudden explosion of discontent following an economic downturn in the late 1970s. The independent-minded Farah, The Fall of Heaven underlines, was known for speaking up. Accounts like Nahavandi’s claim she never broke the cordon sanitaire around the shah. But Cooper reveals a series of sensational meetings between the queen and Parviz Sabeti, a senior officer in the shah’s feared intelligence services, who went to the queen with his dossiers on the corruption among courtiers and the royal family, after being stonewalled by his superiors. “How can my son,” Farah cried, “become king if this is going on?” When the shah heeded such warnings, it was too much, too late. In early November 1978, he acquiesced to the arrest of dozens of former officials, among them Hoveyda, recently dismissed from office, whom his rivals denounced as responsible for the regime’s greed.

Only when things began to go patently wrong, after student protests erupted in the religious city of Qom in January 1978, did the queen’s political influence become decisive at court, encouraging the shah to pursue his liberalization program and to appease the swelling opposition. In the decade before, the queen had asserted herself as the patron of Iran’s cultural avant-garde—hosting Andy Warhol in Tehran and laying the foundations for the commercial success of a generation of freethinking Iranian artists—as well as causes like rural literacy and environmental conservation.

Yet the shah, like his court minister, had suspected his wife’s liberalism as an import from Paris, where she had studied, and her circle of left-leaning intellectuals as mere devotees of radical chic. “An angel of purity,” Alam said, “but she is inexperienced and impulsive.” The queen could not understand why a man would be jailed for reading Anton Chekhov—and interceded for the release of such prisoners. When the shah turned toward his wife for political advice in his final year on the throne, his congenital suspicion toward her democratic views, unlike what Cooper writes, never really diminished—or his ambivalence about her political role. “You don’t have to be Joan of Arc,” he told the queen, when she offered to stay behind as a symbol for the few royalists left.

By the time the shah began a program of liberalization—relaxing, as he had suppressed years before, freedoms of press, speech and protest—it was too late. Muhammad Reza had always displayed fastidious respect for counsel and the letter of the constitution whenever his authority was weakest. It is, however, difficult to judge the sincerity of princes. “The problem this time was that no one, not his most devoted supporters, and certainly not his foes,” Cooper observes, without irony, “could imagine that the king who relished power as much as he did would ever voluntarily relinquish it.”

It is no wonder a thin web of counterfactuals hangs over The Fall of Heaven—the success of revolutions like the Iranian, or the Russian or the French, rely upon magnificent contingencies. Cooper even suggests that the disappearance of the Iranian-Lebanese Shiite leader, the Imam Musa Sadr, while visiting Libya in August 1978, foiled a brewing concordat between the shah and Iran’s senior clergy, who by and large were wary of Khomeini’s radicalism. The New York Times review judged “fanciful” the theory that Sadr, however charismatic, could have reversed the course of Iranian and Shia history.

What might have happened differently has been, since the shah’s exile, the ceaseless parlor game of ancien régimistes. Cooper’s book, perhaps unintentionally, plays along, encouraging the reader toward the conclusion that—had the shah not been weakened by cancer, or had Carter more firmly expressed his support for the monarchy, or had the Iranian people been grateful for the shah’s many real achievements—Iran would have moved toward a benign, British-style constitutional monarchy. “The Shah spent the last two and half years of his reign,” Cooper concludes, “dismantling personal rule in an attempt to democratize Iranian political life.”

Few historians will agree with Cooper’s out-and-out revisionism. That the shah was planning free elections—conveniently in the future—obscures the point of his anti-democratic character. His most ardent loyalists, chief among them Alam, knew this. Biographers of the monarch’s last years, beginning with William Shawcross’s unsurpassable The Shah’s Last Ride (1988), have always understood that he was as much an opportunist as he was a visionary—how else could he have survived 37 years on the Peacock Throne? Then again, curiously, The Fall of Heaven—whose title recalls the country’s halcyon days as an economic and political leader in the Middle East—reflects how many Iranians feel today. “This sober narrative,” the exiled journalist Nazila Fathi wrote in the Washington Post, “will resonate with many Iranians—including myself—who lived under the grim conditions Khomeini introduced after the revolution.” Historians should resist the temptation to view the past as mere prologue, however grim the present.

The Iranian revolution, we can say glancing at the tempest of Islamic movements that swept the world afterward, was one of the foundational events of the twenty-first century. But it would be a mistake to say that history has vindicated the après-moi-le-déluge attitude of the shah. The Iranian historian Abbas Milani in The Shah (2011), a far more balanced portrait, concludes that Muhammad Reza “arguably made the worst possible choice” at every critical juncture in the revolution. The shah’s story resonates with us as the tragedies of Sophocles or Shakespeare do—as tales of the hubris of men who believe they are doing good, but who instead work horrible mistakes.

And indeed, Cooper reminds us that the American and British actors in the tragedy of Iran’s revolution were as hapless as anyone else. “We should be careful not to over-generalize from the Iranian case,” Carter’s national security advisor wrote the day after Khomeini’s return to Iran. “Islamic revivalist movements are not sweeping the Middle East and are not likely to be the wave of the future.”