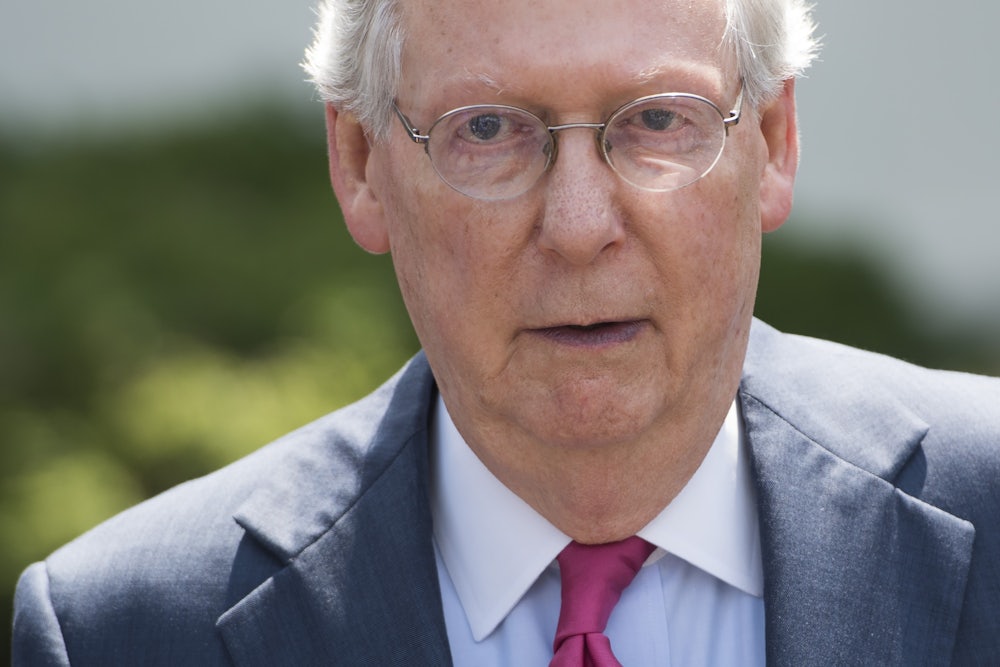

The climax of the Senate Republican health care fight bill is coming into focus and points for consistency: It’s just as stupid and nihilistic as the process leading up to it has been, and will give way to yet more stupidity if it works as Majority Leader Mitch McConnell hopes.

The idea is that late in the week, as the Senate votes in rapid-fire succession on a glut of amendments (a mandatory process known colloquially as vote-a-rama), McConnell will introduce a final amendment that trumps all the others. Republicans have taken to calling this plan “skinny repeal,” which describes a scaled-back health care bill whose main effect of would be to eliminate the Affordable Care Act’s coverage requirement: the individual mandate. McConnell’s amendment would wipe out everything that came before, and substitute this “skinny repeal” in its place.

As I argued here, the moniker “skinny repeal” is a devilish piece of spin, because while it accurately describes the breadth and ambitions of the plan, it completely misdescribes the consequences of repealing the mandate, which would be severe. According to recent Congressional Budget Office findings, repealing the individual mandate alone would lead many healthy people to drop their coverage, precipitating an increase in insurance premiums that would drive sicker people out of the market reluctantly. Combining these interlocking effects, the CBO forecasts the coverage loss would amount to 15 million people.

While “skinny” isn’t a particularly honest word for a bill that would ravage insurance markets in this way, it is a great device for allowing Republican senators to pretend their vote isn’t particularly meaningful—that it’s a placeholder allowing the congressional health care debate to continue. But just as it is unwise to take Senate Republicans at their word when they say they will vote against a bill, it is also unwise to assume that the not-so-skinny repeal bill would just move the legislative process into its next, penultimate phase: the conference committee, where House and Senate Republicans would hash out a final bill.

It is just as likely, if not more, that the real endgame is to repeal the mandate, sabotage the insurance markets, and then return at a later date to inflict more damage on the health care system. It is safer, in many ways, to assume you are being lied to again, rather than to believe that Republicans senators weighing “skinny repeal” are trying to be constructive.

The genius of a bill that does little other than repeal the individual mandate is that Republicans can’t easily vote against it. Because it’s the most broadly unpopular provision of Obamacare, Republicans have raged against it more than any other part of the law. Thus, it is hard to imagine enough Senate Republicans voting against the measure, which is already drawing enough support or attention from endangered Republicans to raise expectations it will pass.

But there are reasons to doubt the purpose of the disastrous skinny bill is, as GOP Senator Bob Corker claimed, to serve as a “forcing mechanism” for getting to conference with the House. A conference may or may not happen, but there are many reasons to expect that the product to emerge from it would look much more like the “skinny” Senate bill than the “mean” House bill.

In the main, that’s because any legislation that emerges from the conference committee would be subject to a Senate budget rule that requires majority-vote measures like the health care bill to be strictly fiscal in nature. All taxes and spending, no regulation. Conference committees, now exceedingly rare, are tightly controlled by House and Senate leadership, and the imperative would be to advance the lowest-common-denominator, budget-only bill that could pass both chambers. That’s a repeal of the individual mandate.

Moreover, there is a line of thinking on the right which holds that repealing the mandate first, on its own, would be a strategically shrewd way to break into chunks a single bill, the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA), that would uninsure more than 20 million people.

(12/X) After mandate repeal, CBO would be forced to score coverage provisions of GOP replacement under a voluntary insurance market.

— Avik Roy (@Avik) July 23, 2017

Roy, who has heaped praise on the Senate health care bill while refusing to say whether he helped write it, posted that tweet days before the term “skinny repeal” entered the health policy lexicon. Now that eliminating the mandate alone is in the offing, he has published an op-ed amplifying this death-by-many-cuts strategy.

Because the CBO contends that the mandate has a profound effect on coverage levels, Republicans could smuggle most of the coverage loss of a more complete repeal by doing a mandate repeal first, and celebrating it as a blow for liberty. At that point, the 15 million person coverage loss will be baked into CBO’s baseline. If Republicans were to then return to their health care repeal efforts with legislation to gut Medicaid and slash subsidies, they would no longer have to contend with brutal CBO forecasts that project stratospheric coverage loss levels. Instead of reducing coverage by 22 million people, the CBO would tally the coverage loss from their second-phase bill at a more modest five-to-ten million.

Just getting to a second phase of health care legislation would be very complicated in its own right, and it’s possible that in the final analysis, the repeal process will begin and end with the individual mandate. But that would still be a far cry from the budding claim that voting for “skinny repeal” is just a vote to help the process along. It’s a vote to uninsure millions of Americans.