Meticulously choreographed military parades. Strident news announcements on state television. Missile tests presided over by a grinning Kim Jong Un. Propaganda from North Korea comes to us fully formed and almost alluring in its opacity: a finished product that has been carefully constructed to convey an idealized image of strength and unity.

Carl De Keyzer, a photographer based in Belgium, offers a different and more intimate view: a glimpse of the process of indoctrination within North Korea. From their first day in kindergarten, children are spoon-fed propaganda—from lectures about the legendary feats of Kim Il Sung to field trips to a museum that depicts, in gruesome detail, Americans massacring Koreans. What makes the images all the more remarkable is that De Keyzer was subject to the same restrictions imposed on foreign tourists who visit North Korea. During his four trips to the country over the past two years, he was attended at all times by official minders, and had to submit his photos for state approval. As a result, we see only the images the regime wants us to see—a sunny, utopian view of a nation where, in reality, some 70 percent of the people struggle to put food on the table, and most live without running water, heat, or electricity.

Yet through his keen eye and careful framing, De Keyzer helps us see beyond the official picture. A mural of children dressed as soldiers wielding rifles looms over an exhibit of colorful toys. A state-produced music video serenades diners with footage of blazing howitzers. A mother beams at her son in the only village where foreigners are permitted to spend the night at a Korean home selected by the state. The images do not show us what is kept out of the frame. But within their narrow confines, they reveal much of what is meant to remain unseen.

As the first American journalist granted permission to join the local press corps in Pyongyang, I know firsthand how important it is to see North Korea in all its complexity. The effect of De Keyzer’s work is not to sanitize the regime, but to underscore just how deeply its militarized worldview is woven into the fabric of everyday life. Such glimpses have never been more important—especially now, as our own leader exhibits a “locked and loaded” mind-set that would be right at home in Kim Il Sung Square.

A topographic map in the science room at Toksong Primary School, in the provincial city of Phyongsong. The map emphasizes the militarized might of the North and omits the four-mile-deep Demilitarized Zone—one of the world’s most heavily armed borders—that has divided the Korean peninsula since 1953.

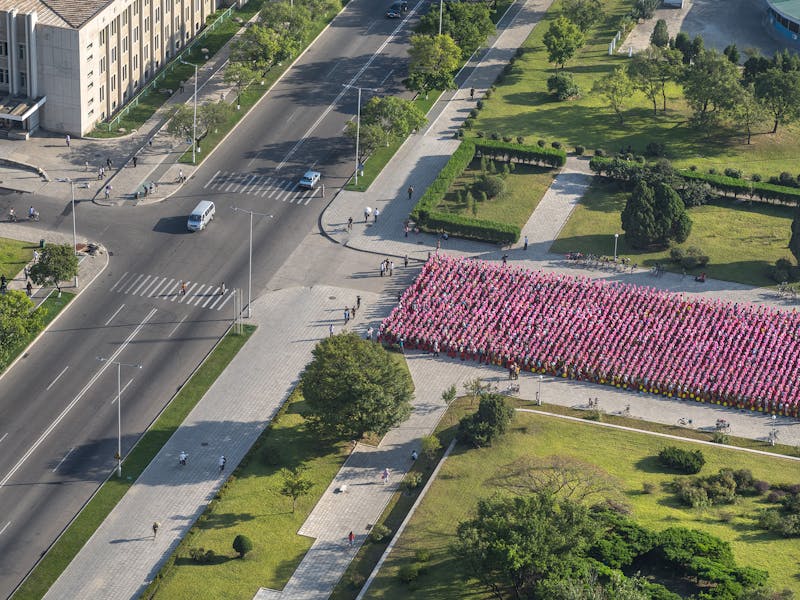

Koreans rehearse a mass rally beneath the Juche Tower in Pyongyang—a display carefully framed for foreign journalists. Rallies celebrating ballistic missile advancements are a hallmark of the regime, with citizens clutching placards bearing slogans like: “Let’s Become Bullets and Bombs Devotedly Defending Respected Supreme Leader Comrade Kim Jong Un!”

A mother and son at the remote Homestay Village near Mount Chilbo, one—if not the only—place where foreigners are permitted to spend the night with a Korean family. The well-furnished homes, surrounded by an electric fence, offer no trace of the hardships endured by most rural families.

A mural of children firing rifles and playing with fighter jets hovers over a display of toys in the Three-Revolution Exhibition House. North Korea has the fourth-largest active military in the world; the Red Youth Guard has an estimated one million members between the ages of 14 and 16.

Students stand below a beaming portrait of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il in Pyongyang’s Sci-Tech Complex. Their birthdays are public holidays in North Korea, celebrated with lavish festivals, fireworks, and pilgrimages.

Men in Pyongyang file through the refreshment line at an exhibit of 3D photographs. North Korea likes to showcase itself as a technological power, but its GDP is among the lowest in the world—only $1,700 per person, compared to $37,900 in South Korea.

Swimming lessons in Pyongyang’s Changgwang-won Health Complex. Mass synchronized swimming displays are popular in North Korea. They’re performed regularly during gala events and anniversaries of supreme leader Kim Jong Il’s birth.

A ride at a fair in Pyongyang. While in North Korea, tourists are ferried to amusement parks built under Kim Jong Un—a roller coaster aficionado who has launched a push to construct new leisure facilities, from the country’s first ski resort to a shiny new water park in east Pyongyang.

Howitzers in a state-produced music video at a restaurant in Pyongyang. Film and music are some of the most potent tools the government uses to disseminate propaganda. Before he died in 2011, Kim Jong Il owned some 30,000 films, including every Oscar winner, and spent lavishly to fund movies designed to highlight the country’s military prowess.

Commuters at a Pyongyang subway station pass Rodong Sinmun, the country’s largest state-sanctioned newspaper. While many elites now subscribe to a digital edition of the paper, nearly 600,000 citizens still read copies posted at libraries and factories.

Locals and travelers watch a film on a public screen near Pyongyang Station. This screen in the center of the city shows soap operas throughout the day, as well as important news broadcasts, such as the announcement of nuclear or missile tests.

In a diorama at the Sinchon Museum of American War Atrocities, U.S. soldiers are depicted driving a nail into a Korean woman’s head. The regime uses the museum’s gory displays to foster an unsubstantiated narrative that American-led forces massacred 35,000 civilians in Sinchon in 1950.

A spectator offers a paper flower to a soldier after a large military parade in Pyongyang. North Korean men are required to serve in the armed forces for ten to twelve years. Women spend roughly six years in the military, between the ages of 17 and 23.