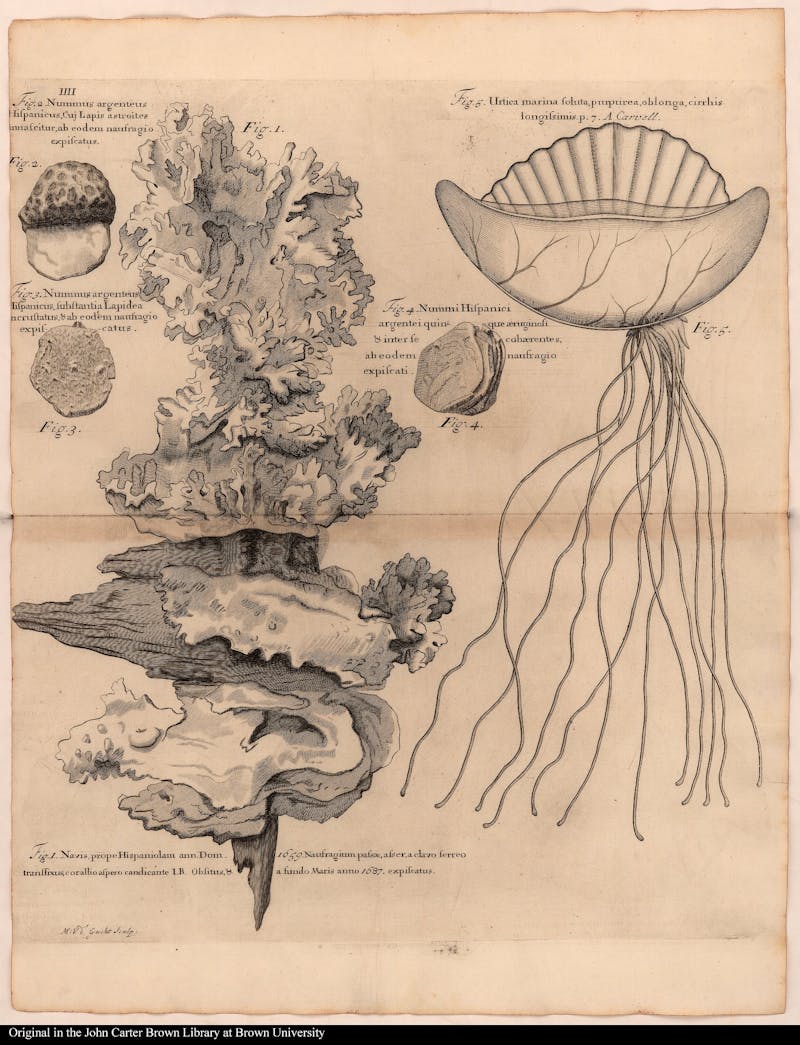

Hans Sloane (1660-1753) owned a spar from a Spanish treasure ship that sunk in the Caribbean Sea. Lying for years the ocean floor, the spar—a pole used in the ship’s rigging—became encrusted in coral. In his vast private collection of object, categorized as Vegetable Substances, Quadrupeds, Antiquities, Medals and Coins, Mathematical Instruments and more, Sloane’s spar was catalogued under both “Corals” and “Miscellaneous Things.”

Hans Sloane’s collection was a private one, but it became public after his death. According to the wishes laid out in his will, the House of Lords “passed the British Museum Act between discussions of a bill for preventing disease in cattle and the setting of a prize for discovering longitude at sea, and on 7 June 1753 George II gave his royal assent.” The collection formed the basis for the new British Museum, which of course expanded into something much bigger in the decades and centuries to come—it still plays host to the biggest and best exhibitions in London. Born in Ireland to a pretty ordinary family, Sloane became a well-connected and powerful baronet whose collection was hugely famous and whose career, founded on medical practice and natural history, led him to the presidency of the Royal Society, the learned group whose leadership he inherited from Sir Isaac Newton, and which Sloane presided over until his retirement at age 80.

Collecting the World, a new biography of Sloane by James Delbourgo places this extraordinarily influential man in the context of his time, describing his non-aristocratic birth, his rifts with other Royal Society members, and the deep complicity he and his collection enjoyed with slavery and imperialism. But it is Sloane’s collection itself—all those dead little butterflies, all those things stolen from enslaved people, all those antique coins—which speaks the most eloquently about its owner.

Take the coral-encrusted spar. The principle of encrustment itself feels descriptive of Sloane: He liked to layer things on top of each other, to create new ideas through juxtaposition. There’s a lack of order to the encrusted thing; a lack of borderline between the man-made and the naturally-occurring; a lack of material distinction between the spar, which was after all a product of plunder, and the Caribbean Sea itself.

The spar demonstrates the principle of accumulation. Sloane enriched his “cabinet of curiosities” through tireless accretion, adding and adding and never taking away. Like the spar, which was made bigger by the arbitrary addition of coral on top of it, more and more objects joined Sloane’s collection each year, swelling it to enormous size. In this, Sloane followed his hero Francis Bacon, who, Delbourgo writes, “called for restoring English fortunes by rebuilding the stock of knowledge through travel, experiment, and the collection of matters of fact. Sloane was thus content to accumulate rather than theorize.” He was a gatherer, not an analyst.

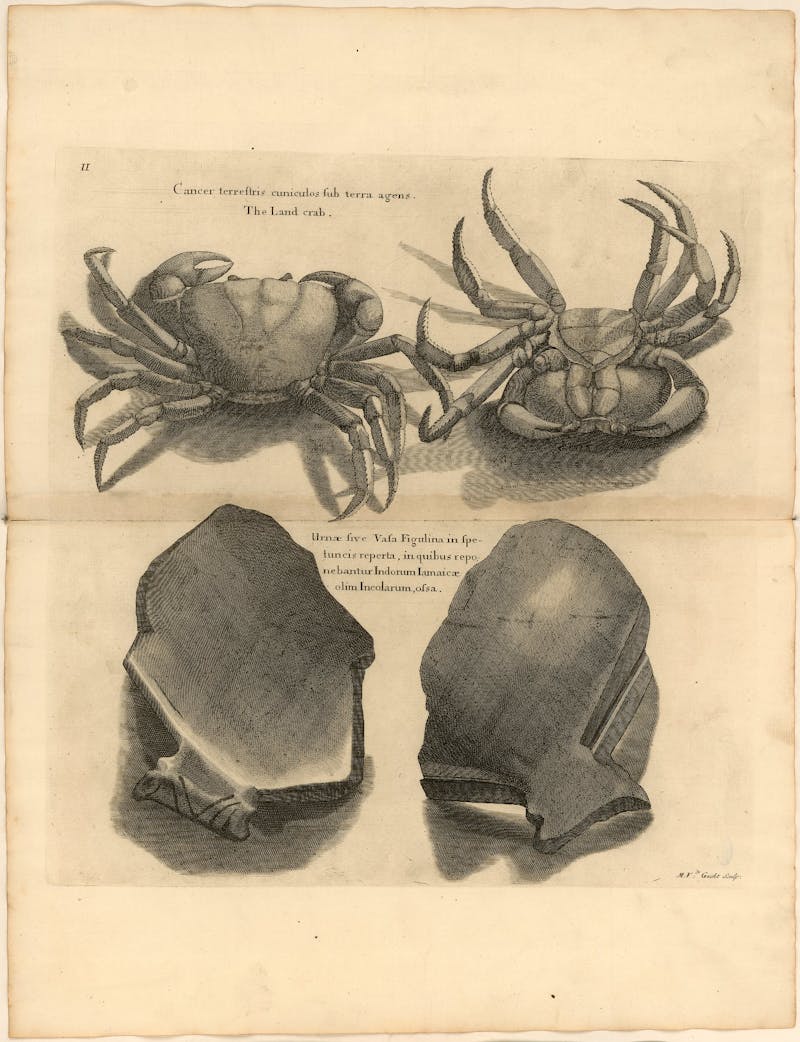

Sloane collected so many things because he did not believe that a single instance of a species could be a true example of it. Within this first principle lies a subtler and perhaps more important concept—that of the specimen. A man named James Empson, the son of Sloane’s housekeeper, became a trusted assistant in keeping his collection. Empson described Sloane’s possessions as differing by “their colour, or shape, or impressions and marks on them, transparency or opacity, softness or hardness, different mixtures either in them or adhering to them,” or “places of nativity.” Each different example of a species (a plant, a rock) are “so differently distinguish’d productions of nature,” Empson writes, that they “cannot be called the same, or be represented by one sample, but that they are different specimens, though going under one general name.”

This is not the way that we think of species now. Delbourgo writes that “Sloane appears to have shared a version of the so-called “species scepticism” of his friend John Locke.” This set of ideas would have collectors do their best to “identify distinct classes of object” but to acknowledge that “such classifications were to some extent arbitrary; they did not adhere to the true order of nature because it remained beyond human knowledge to apprehend the real essences of things as God created them.” Sloane’s enormous collection of things aimed to “coppy” the world, to make a testament and tribute to the creative genius of God. But god works with infinite variety; so must a collection.

Sloane journeyed to Jamaica in 1687 as physician to the Duke of Albemarle, the new Governor. He was fascinated by the flora and fauna of the island. He was especially keen on “the dessert after dinners, which consisted of shaddocks, guavas, pines, mangrove-grapes, and other unknown fruits in Europe, that I thought all my fatigues well bestowed when I came to have such a pleasant prospect.”

Delbourgo is admirable in his reading of this layering of slavery and natural history in Jamaica. As he observes, enslaved people “remade Caribbean landscapes by clearing and harvesting plantation land, while plants and animals,” like the Guinea grass that fed so much livestock, “travelled west to the Americas” from Africa, on slave ships.

Every conversation had and every object taken by Sloane in Jamaica (in the effort towards writing his Natural History of Jamaica) was a part of the system of slavery. Even his “entomology:” Sloane was interested in worms, particularly those which infected the bodies of enslaved people and ships. He collected “manati” whips, which were made from manatee leather and not often used because they so damaged the skin of an enslaved person that her resale value was compromised. Sloane acquired a “noose made of cane splitt for catching game or hanging runaway negros.” He used enslaved people as guides to the trees and animals of Jamaica. Meanwhile, Sloane was sent treasures from West Africa by friends who sold human beings: clothes, beadwork, shells.

And Sloane, the founder of the great public institution of the British Museum, owned a plantation. In 1695, he married the widow Elizabeth Langley Rose. Elizabeth’s first husband had been “one of Jamaica’s leading slave owners, reckoned to be one of only six colonists who regularly purchased hundreds of Africans in the 1670s.” She inherited the estate, and that became Sloane’s when he married her a year after her first husband’s death.

There can be no doubt that Sloane’s attempt to obtain a version of the entire world in his private collection resembles the British imperial mania for ownership over lands and peoples. The coral-encrusted spar itself was recovered, Delbourgo records, by coerced Native American, East African, and East Indian divers. That Sloane was himself so happy to profit from the enslavement of human beings, harvesting his income from abroad while tending to his garden of marvels in London, bespeaks the politics that soak his collection. That coral-encrusted spar felt, to Sloane, like it was his. The Caribbean sea floor, the treasure ship, the plunder and the nature all at once—all Sloane’s for the taking.

Working as a phycisian in Jamaica, Sloane would tenderly minister to the drunken colonist whites, of while accusing any enslaved person of faking their pain. In the monstrous racism of the writings he made about his practice, and the higgledy-piggledy anti-speciesism of his collection, there is something surreal about Sloane. In his pharmacopoeia drawers, Delbourgo writes, Sloane kept “goats’ blood, a moss-covered human skull, burnt deer antlers, burnt ivory, bones from the hearts of deer, beaver glands, rhino horns, silk-worm cocoons, crab claws, boars’ teeth and a mummy’s finger.” Through his connections in present-day South Africa, he obtained “an orang-uutang from Batavia (Jakarta) and a ‘homo sylvestris’ from Borneo; an elephant’s brains contained in a gold case originally from the Sultan of Jambi (Sumatra); a large Sumatran bat.” In his Humana category, Sloane owned “a fetus of 7 months old resembling a monkey wt a cloak which the woman saw playing tricks at Rochester.”

Delbourgo’s stories about Sloane’s journeys are also touched with a hint of madness. When Sloane left Jamaica, he filled his ship with species both dead and alive. He was very fond of a certain snake. Quoting Sloane, Delbourgo writes that the “snake had grown ‘weary of its confinement,’ broken out of its container and writhed its way to the sleeping quarters of the duchess’s servants, where they shot it dead.” Other species suffered the same fate. Sloane had packed an iguana, but when “running along the gunnel of the vessel” it was “frighted by a sailor and leap’d over board and was drown’d.” (Sloane fared better with some other species: after a contact sent him a live porcupine, he kept it alive in his garden in England, feeding it carrots.) Delbourgo also records a visit to Sloane paid by “George Frideric Handel, when the great court composer damaged one of Sloane’s manuscripts by placing a buttered muffin on it (‘it put the poor old bookworm terribly out of sorts,’ Handel reportedly observed)”.

Sloane’s collection feels surreal, or even adjacent to insanity, because it contradicts the very order of things as we know them. For us, “nature” and “society” belong to two separate realms. As Bruno Latour has described, this division of the world is what separates science from the humanities; environmentalism from poetry. The coral-encrusted spar does not wholly belong to any single category. It is not mostly coral, nor mostly treasure ship, nor mostly artifact of racist capitalism, not mostly Caribbean seabed. It is a hybrid thing that Sloane felt was special because it was singular, and in that singularity it demonstrated the infinite presence of God. For us, its singularity represents something different: How nature, invention, enterprise, and curiosity can all become woven together with the thread of human cruelty.

The profit that Sloane reaped from the enslavement of his fellow human beings and the total absence of humanity that he saw in those human beings is also surreal to us—or at least it should be. There are aspects to Sloane’s vision of the world that are simply outside our notion of the real. For this reason alone, Delbourgo’s biography is a prodigious contribution to our understanding of where that boundary lies.

Sloane lives on in the British Museum itself, which has dispersed his collection to different departments. But this book is a fitting tribute to his contradiction-riven life. Collecting the World is about the torment of slavery, and it’s about buttered muffins and about snakes shot on boats. It teaches us about how we know, how we organize and discipline our knowledge, by the specimen of this strange, cruel, and single-minded gentleman doctor of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.