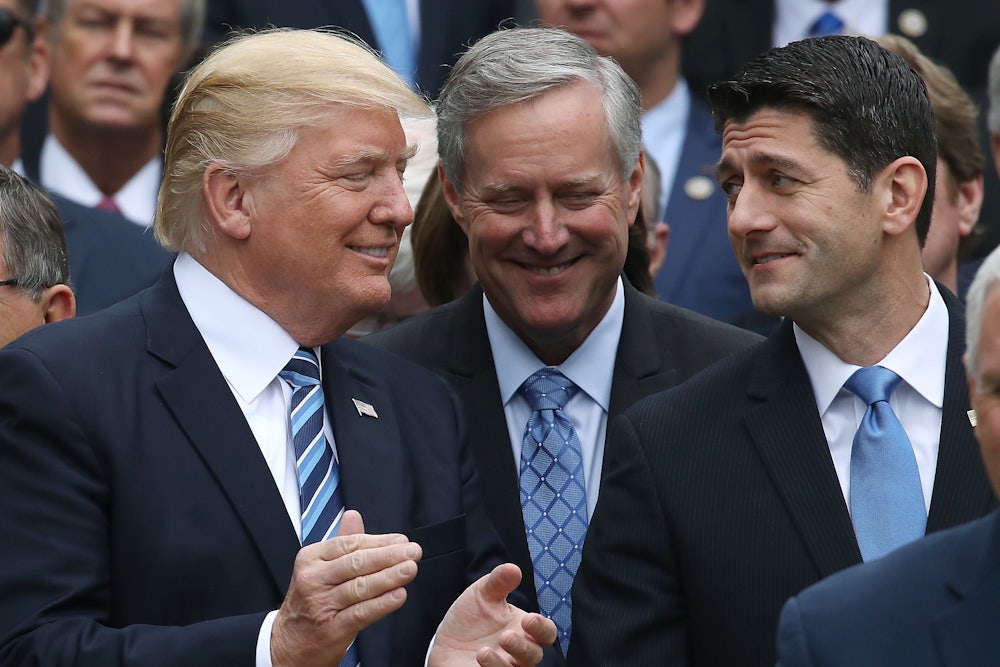

The failure of Republican efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act confronts President Donald Trump and his party with the once-unthinkable possibility that the year will end without a single significant Republican bill becoming law.

By zeroing out all of Obamacare’s taxes, health care repeal was meant to grease the skids for the GOP to rewrite the entire tax code, the combined effect of which would be to overwhelmingly benefit high earners.

But as the Trumpcare process dragged on, and once it ultimately collapsed, a conventional wisdom began to gel that Republicans would have to settle for large, temporary tax-rate cuts, much like those George W. Bush passed in his first term, rather than a more thoroughgoing and lasting tax reform.

From where I sit, though, it seems unlikely that Republicans will be able to muster even that. It is true that Republicans love to cut rich people’s taxes, and most of them are eager to do so before the end of the year. But it is also worth recalling that Bush Republicans didn’t have the easiest time in the world passing its first round of tax cuts—it briefly cost them control of the Senate—and, in many ways, today’s Republicans face more obstacles than their predecessors did.

The following complications either didn’t exist in 2001 or weren’t as severe then as they are today:

Polarization: Today’s two-vote Senate GOP majority is technically larger than the zero-vote Senate GOP majority in 2001, when Vice President Dick Cheney served as tie-breaker, but multiple Democrats voted for the first Bush tax cuts. It is a safe bet that fewer if any of today’s Democrats will vote to help Trump cut rich people’s taxes.

Preparation. Bush-era Republicans made cutting taxes their top priority. They thus kicked off a budget process in the early weeks of his presidency that allowed them to circumvent a filibuster of tax cut legislation and, if need be, pass it with Republican votes alone. By trying and failing to repeal Obamacare before addressing the broader tax code, today’s Republicans will enter the fall without a process in place to avoid a Democratic filibuster. That means that before they do anything, they will have to write and pass another budget, which is a tall order in its own right.

Calendar. But they don’t really have time for it anyhow, because they spent the spring failing to pass Trumpcare, and the summer on a lengthy recess. When they return in September they have to, among other things, increase the debt limit, pass annual spending legislation to prevent a government shutdown, reauthorize a children’s health insurance program, and most likely pass a supplemental spending bill to fund the Hurricane Harvey recovery effort. Which brings us to the fact that . . .

There Was Just a Massive Hurricane and a Biblical Flood. There is perhaps no better distillation of Republican thought than mounting a political campaign for massive millionaire tax cuts in the midst of an enormous natural disaster, but the public at large isn’t nearly as monomaniacal about cutting rich people’s taxes as the Republican Party is. To the contrary, cutting rich people’s taxes is very unpopular. And the dissonance of trying to funnel money up the income scale to rich people when it’s needed down the income scale for hurricane and flood victims won’t be lost on the entire public.

The Uncanny “No Reason to Cut Taxes” Valley. Even if Hurricane Harvey had never materialized, the broader political and economic climates in the United States would be uniquely ill suited to passing a big regressive tax cut. When Bush was running for president, the budget was in surplus, so he advocated tax cuts as a way to return the surplus to taxpayers. When he took office, the country was entering a recession, so he advocated tax cuts as a way to juice the economy. These were thin pretexts, but there was a superficial logic to both arguments. Right now the economy is growing, the budget is in deficit, and perhaps most important of all, rising inequality is 16 years further along than it was back then. Cutting rich people’s taxes couldn’t be more out of step with the zeitgeist.

Trump Is the Worst Possible Avatar for Tax Cuts. As if to exemplify all the reasons it makes no sense to cut rich people’s taxes, Trump is extremely rich, is trying to cut his own taxes, and is also trying to hide that fact—and the magnitude of the tax cut he wants to give himself—by refusing to disclose his tax returns. This might not be a huge drag on Republicans if Trump weren’t also exceedingly unpopular, but . . .

Trump Is Exceedingly Unpopular. His unpopularity will make any tax initiative he touches unpopular, which in turn will make it easier for vulnerable Democrats to oppose it. But Trump is also pretty unpopular among elected Republicans. He’s feuding with GOP leaders and has made real enemies of a number of GOP senators whose votes he will need. Most of them will probably be able to set aside their personal feelings and vote for tax cuts (which they in general really like), but Trump can lose only two Republican votes. Depending on John McCain’s health or his maverickiness at the moment, Trump’s effective margin might be only one. Which is unfortunate for him because . . .

Trump Is Incompetent. Trump likes to claim that he’s signed a record-breaking number of bills, but also, incongruously, that Democratic obstruction is preventing bills from passing. At some level he knows his presidency is a failure, because he’s desperate for “wins,” but he lacks the focus, curiosity, and intelligence required to quarterback any contentious legislation through Congress.

The only new countervailing pressures here stem from Trump’s and the GOP Congress’ mutual desperation not to be seen failing spectacularly, along with their mutual interest in not collapsing back into recriminations. Those are important forces, and they may ultimately prevail, but I am not betting on it.