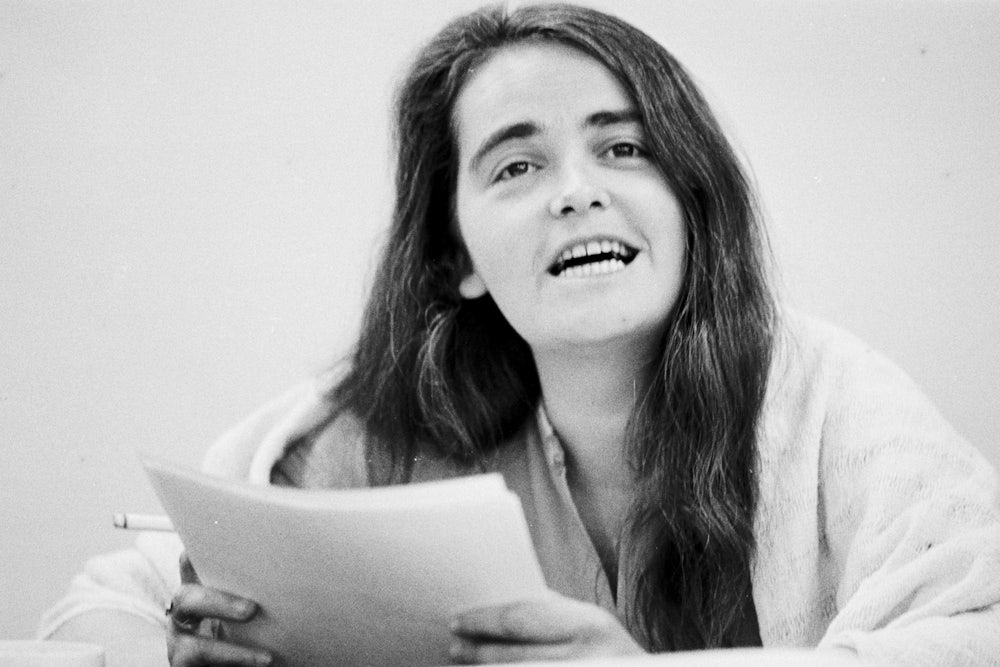

Kate Millett, who died on Wednesday at 82 in Paris, didn’t set out to become a leader of Women’s Liberation. She was not a natural politician, for one thing. Her moods were variable, her ideas somewhat abstruse. She didn’t have the glamour of Gloria Steinem, or the political savvy of Betty Friedan. She was brilliant, to be sure—she had finished college early and had received first-class honors at Oxford—but she was made for the library, not the podium. More importantly, women’s liberation was supposed to be a leaderless movement. Hierarchy was male and oppressive; leadership structures conflicted with the idea of “sisterhood.” If you, like Millet, ran in New York’s radical feminist circles in the late 1960s, you were careful to avoid suggesting that you were superior—or even, simply, different. If you demonstrated expertise, or exercised leadership, you might be charged with being “unsisterly.”

And yet Millett rose to prominence precisely because of her academic expertise. When Doubleday published her book Sexual Politics in the spring of 1970, her bohemian life was transformed. The book, a rigorous work of scholarship that combined literary criticism with history and political philosophy, put forward a theory of patriarchy—what she called “the most pervasive ideology in our culture”—and demonstrated how social institutions, such as monogamous marriage and the nuclear family, buttressed male supremacy. But Millett didn’t stop at the social; culture, too, played a role in shoring up patriarchy. A Victorianist by training, Millett also analyzed how male writers, both canonical and contemporary, portrayed heterosexual relations; she found that all too often, male literature suggested that men had a right to dominate women—politically, socially, sexually.

Sexual Politics was as dense and heavily footnoted as any academic monograph, but it became an unexpected bestseller and went through four printings by summer. The New York Times called it a “rare achievement” and “a piece of passionate thinking on a life-and-death aspect of our public and private lives.” Millett ascended to something like fame. Interviewers tromped through her Bowery apartment; TV talk show hosts invited her to speak onscreen. The phone rang so often that she simply stopped answering it. According to one would-be interviewer, “getting in touch with Kate Millett these days is only slightly less impossible than making a lunch date with Golda Meir.”

The attention challenged the feminist movement, as well as Millett herself. Feminism had been resurgent in the United States since at least 1963, when Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique recast the happy American home as a “comfortable concentration camp.” But Millet’s branch of radical feminism was only a few years old, and its goals were still being formed. In 1967, at a New Left conference in Chicago, Shulamith Firestone and Jo Freeman tried to put the status of women on the agenda; the male leftists laughed, then literally patted one of them on the head.

Firestone and Freeman responded by forming leftist feminist organizations, first in Chicago, then in New York City. By 1970, there were a range of radical feminist organizing cells, including but not limited to: Redstockings, Radical Mothers, Media Women, Bread and Roses, WITCH (for Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell), and BITCH (for nothing). These groups had a set of common goals: equal pay for equal work, abortion on demand, and state-supported childcare. But the radical feminist movement was also riven by internal disagreements over goals and tactics, not to mention interpersonal conflicts among some of its leading organizers. When the media asked Millett to speak for the feminist movement, it was asking her to take a stand on contentious, unresolved issues. Was marriage really slavery, as Ti-Grace Atkinson once said? (Millett herself had a husband, the Japanese sculptor Fumio Yoshimura; they married in 1965, to avoid his deportation from the U.S.) Where did she stand on what the media called “the lesbian issue”? What was the future of the movement? Millett hated the attention and the responsibility. In her memoir of this time, Flying, she recalled visiting a number of college campuses and wanting to “slap their smug little faces and tell them I’m vomiting with terror.”

Exhausted, anxious, and yet still boldly utopian, Millett occupied the limelight during some of the most exciting, fractious years in the history of American feminism. Her life reminds us of how hard it has always been to generate and sustain a social movement, and how much her generation of feminists gave us.

Looking back on her childhood in 1970, Millett saw how some of her early experiences laid the foundation for her feminist consciousness. She was born in 1934 to Irish Catholic parents living in St. Paul, Minnesota. She was the second of three daughters. As she later told Time, her father was disappointed by the lack of a son: “I remember seeing my father getting the news that the youngest was born … the look on his face: three errors in a row.” He beat her and her sisters, then left the family when she was fourteen. Her mother, who had a college degree, struggled to find work that paid enough to support a family. Though women had always worked, their labor was often constructed as incidental. Men were seen as the breadwinners and compensated accordingly. This hadn’t changed by the time Millett wrote Sexual Politics: in 1970, the median wage for full-time female workers was less than 59 percent of that for male workers. On average, a woman needed a college degree to out-earn a man with an eighth-grade education.

Millett entered the University of Minnesota when she was seventeen. She finished early, graduating magna cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa, then took off for England, where she studied Victorian literature at Oxford. As her studies were winding down, she wrote hundreds of letters of inquiry in the hopes of finding a teaching job in the United States. Hundreds of times she was turned down. She wound up in New York, where she taught kindergarten in the city’s public schools. About this time, she later quipped that it illustrated how to go from “Oxford to the Bowery in one easy lesson.”

She solved her problems by taking flight once again: in 1961, she left for Tokyo, where she began making “chug” sculpture, bits of scrap designed to look like soapbox-derby cars. It was during this time that she met Yoshimura; the two moved to the U.S. together in 1963. Millett began teaching English at Hunter and Barnard while pursuing a Ph.D. in comparative literature at Columbia.

In the winter of 1964-65, she attended a lecture series called “Are Women Emancipated?” She wasn’t sure what to expect. At this time, Millett was what Yoshiumura later described as “a very ordinary American liberal.” Her relationship to her female identity was complicated; men in her life had told her that she was neurotic, and that she needed to be more feminine. By the end of the class, she was galvanized. After the second lecture, she recalled, “a girl came up to me and said, ‘You look kinda interested in this; did you know there are civil rights for women?’ And I thought like wow, this is for me.”

Millett threw herself into the city’s activist scene. She got involved with the group New York Radical Women, and she took a leading role in the student strike at Columbia. In 1968, the same year as the strike, she gave a paper at a conference at Cornell. The paper was called “Sexual Politics,” and it was, according to Millett, “a fiery little speech directed at girls.” She liked the ideas she’d put forth so much that after the conference, she listened “rhapsodically” to her own talk on tape.

This was the talk that she transformed into Sexual Politics, her study of power and sex in literature and in life. In the book, Millett argued that patriarchy was historical, not natural. Like Simone de Beauvoir before her, Millett emphasized how things like “femininity,” or “womanhood,” were not biological conditions but socially constructed ideals, concepts that can and should be reconsidered. But Millett, like her fellow radical feminists, went further: she advocated for reorganizing society. She wanted nothing less than the eradication of patriarchy. She also argued that many of the novelists who had been praised for writing openly and candidly about sex—D.H. Lawrence, Henry Miller, Norman Mailer—were in fact neither liberating forces nor revolutionary writers: their fiction merely showed the many ways that women are made unfree. (Mailer later responded to Millett’s critique with a typically self-indulgent piece, “The Prisoner of Sex,” in Harper’s.) Millett’s literary analysis was sharp and sustained; it was also groundbreaking. By bringing politics to bear on literary study, reading fiction through what we might call a “feminist lens,” Millett broke with longstanding academic practices of disinterested, “close” reading.

The year 1970 was a banner year for the feminist manifesto. In addition to Millett’s book, readers encountered Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex, Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch, Toni Cade’s anthology The Black Woman, and Robin Morgan’s anthology Sisterhood is Powerful. But Sexual Politics arguably rose above the rest; one reviewer predicted it would become the “Bible of Women’s Liberation.” It offered not only a coherent theory of sexist oppression but also a clear account of how culture—that is, the stories we produce and consume—contributes to inequality. It was ambitious, rigorous, and unafraid.

Millett herself, though, feared angering her friends and fellow organizers. Her fear was well-founded: at a time when the feminist movement was so internally conflicted, it would be impossible to please everyone. Still, she tried. She gave interviews, she flew to speaking engagements, she allowed her portrait to appear on the cover of Time. She came out as bisexual, then lesbian, and she suffered backlash—both from homophobic feminists like Betty Friedan, who wanted to distance Women’s Liberation from gay liberation, and from lesbian feminists who wished she’d come out sooner. Still committed to making art (she exhibited sculpture throughout her life) she bought property in upstate New York for a female artist colony. If, against her will, she was going to be a named leader of the women’s movement, then she was going to find a way to keep her comrades by her side.

The tumult of these years took their toll. She spent some time in a mental hospital; in later books, she would discuss the damage inflicted upon her by the psychiatric profession. (Millett wrote nine books after Sexual Politics—about human rights, mental illness, and her family—though none ever sold as well or was reviewed as widely as Sexual Politics.) Other feminist activists suffered similar fates: some left the movement because of burnout, others because of irreconcilable differences.

That these women struggled, that they suffered, does not mean that they failed. Organizing is hard, exhausting, brutal work. Movements not only foster conflict but depend on it, for it is through disagreement that strategies and positions are refined. It can be easy, from our vantage point today, to romanticize the radical feminists, to think of them as bolder and more united than those of us who have taken up their cause. They were bold, yes, and brave, but they were also human. Their lesson, perhaps, is not to be daunted by the difficulty of organizing but to endure it, and to be hopeful anyway.

To paraphrase a postmodern theorist, it is sometimes easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of patriarchy. But imagine it these women did. Firestone described a world of women liberated from “they tyranny of reproduction.” In her feminist utopia, joy, and sexual pleasure were not eliminated but rather “rediffused,” breaking the constraints placed on them by patriarchy. Millett, too, believed that patriarchy could be destroyed; humanity depended upon it. “If we did not have these rigid sexual roles,” she once said, “we would all have so much more room for spontaneous behavior—for doing things that we feel like doing, for following our own instincts, for being imaginative, for being creative. The great thing about it all is that we could not only change this, but in the process, really improve everything else as well.” Patriarchy, she believed, would eventually become just one regrettable era in human history.

What we might take from Millett and her comrades is their bold, unapologetic utopianism. As Time put it in 1970, the radical feminists wanted “far more” than what most women did: “Their eschatological aim is to topple the patriarchal system.” They were impatient with those who told them that their concerns were unimportant, or that their goals were impossible. Time has given the lie to both these critiques: we now recognize the significance of sex-based oppression, even if we have not overthrown it, and we understand that cultural representations—of women, of sex, of power—help shape the world we live in. “Patriarchy” has entered the lexicon. Some of the major achievements of second-wave feminism, such as abortion legalization, remain intact, at least for now. But as we gather our energy for the next fight, we might think, as Millett did, about how much our world can—must—be changed, and how much work it will take to do so. This is not a reason to shy away from the task. It’s a reason to dig in.