Last week was a momentous one for left-wing politics in America. In a testament to his newfound influence on Capitol Hill, Senator Bernie Sanders introduced his “Medicare for All” single-payer health care bill with 16 co-sponsors. Even former Senator Max Baucus, a moderate Montana Democrat who helped kill a public option in the Affordable Care Act, is now on board. Washington Post columnist Dana Milbank may have been exaggerating when he claimed that “Democrats have become socialists,” but there’s a reason that David Duhalde, deputy director of the Democratic Socialists of America, told him “this is a high water mark” for his ideology. “The left is the rising force in the party,” Michael Kazin, the Georgetown University historian and editor of the leftist Dissent magazine, told me. “It seems to be the part of the party that has ideas—the part of the party that stands for clear reforms.”

But plenty of Democrats aren’t ready to join Sanders in pulling their party left—including the woman who beat him in the 2016 primary. Promoting her new book in an interview with Vox’s Ezra Klein published Wednesday, Hillary Clinton distanced herself from “the far right and the far left, both of whom want to blow up system and undermine it.” She said, “I think we operate better when we’re kind of between center right and center left, because that’s where, at least up until recently, most Americans were.” A decreasing number of Democrats in Washington occupy that band in the political spectrum, but they exist—people like Progressive Policy Institute president Will Marshall and Third Way vice president Jim Kessler. In the face of an ascendant progressive populism—one credited with injecting big, bold policy ideas like single-payer and free college into the Democratic bloodstream—these moderates reject the idea that Democrats are (or ought to be) all socialists now. And they say they’ve got their own ambitious ideas for the party’s future, ones that can actually appeal to parts of the country that handed Donald Trump the presidency.

“We need big and systemic changes in this country,” Marshall told me. “That doesn’t mean they need to be social democratic imports from Europe.... Part of what’s curious about my friends on the left is they think America’s destiny is to become a European-style welfare state.” As an alternative, Marshall is touting “radical pragmatism,” which he defines as “an approach you take when you don’t exactly know the best way forward. Problem solving involves a certain degree of experimentation and trial and error.... We may share the same goal. Unlike them, I’m not saying I know the perfect way to achieve it.” Marshall calls his new group, New Democracy, “a ‘home base’ and support network for pragmatic Democratic leaders” whose mission is “to expand the party’s appeal across Middle America and make Democrats competitive everywhere.” That’s not to say he wants a war with leftists. He simply believes, in the words of New Democracy’s mission statement, “It’s time for Democrats to pitch another big tent.”

“I think the party has to have a broad path—room at the table for both wings of the party to put forth their ideas but not require either side to reflexively take them,” Kessler told me. He says Democratic economic agenda should focus on the “concentration of opportunity in America”—as opposed to focusing on income inequality—with the goal of seeing “that everyone everywhere has the opportunity to earn a good life.” Back in March, he told The New York Times, “How to make the forces of technology and globalization work for people and not against them is the biggest public policy challenge in America.” And Kessler is adamantly opposed to the hottest Democratic idea of the moment: single-payer. “It’s is the wrong policy for this country,” he said. “Forget the politics, which I think don’t work at all.” His view is that transitioning to the new system would be “extremely expensive and wasteful” and “massively disruptive” at a time when the Affordable Care Act has brought the country closer than ever to universal coverage. “We’re at the 10-yard line,” he told me, “Let’s not go back to our own 10-yard line and have to drive 90 yards starting over.”

Democrats across the ideological spectrum seem to agree that their party lacks a clear message in the Trump era—one that can appeal to working-class Americans of all races. House Democratic Caucus Chairman Joe Crowley, when pressed on the subject in July, hesitated before saying, “That message is being worked on. We’re doing everything we can to simplify it, but at the same time provide the meat behind it as well. So that’s coming together now.” The public apparently agrees: A poll that same month found that 37 percent of Americans believe the party stands for something, versus 52 percent who said it just stands against Trump. And the release in late July of A Better Deal, the Democrats’ new agenda, hasn’t quelled this concern.

I’ve argued that Democrats don’t need a core national message to succeed in next year’s midterm elections. But to those convinced they must have one, wouldn’t pitching “another big tent”—that is, broadening the message to appeal to more centrists and independents—only further cloud what the party stands for? Or is that exactly what Democrats must do if they want to have any chance of taking back the House next fall?

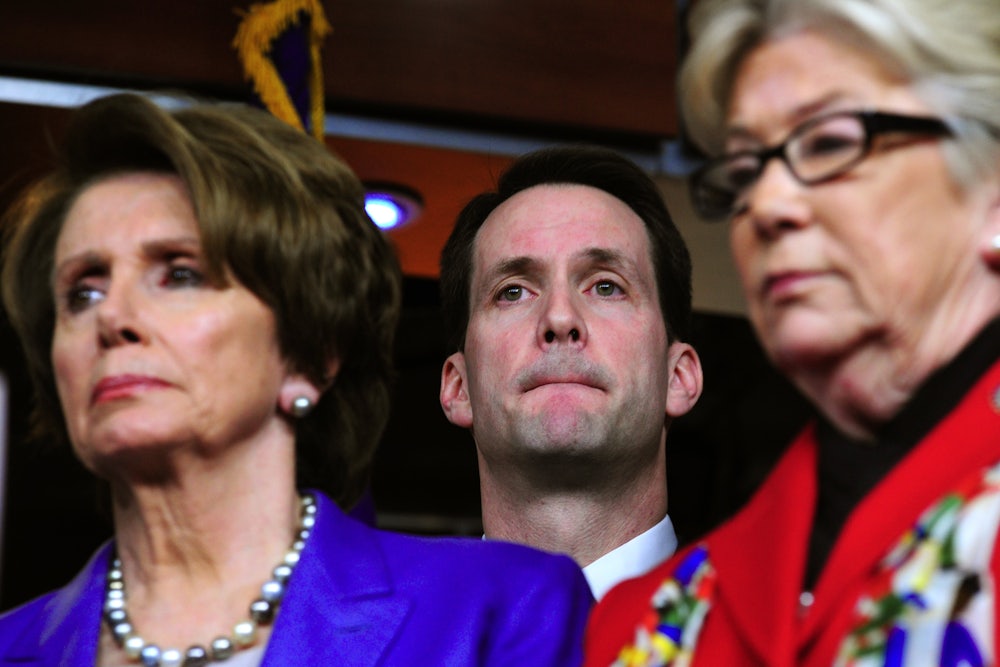

Centrists have a host of worries about the left’s new agenda, the first being that it’s politically risky. They cite a Politico report earlier this week that free college tuition, a $15 minimum wage, and Medicare for All “test poorly among voters outside the base. The people in these polls and focus groups tend to see those proposals as empty promises, at best.” Representative Jim Himes of Connecticut, who chairs the moderate New Democrat Coalition in the House, told me, “There is something in the heart of every American that doesn’t like the concept of being given stuff.” He questions the fairness of a universal free college plan—whether the government should be paying for affluent students to attend school—and the intensity of Medicare for All supporters. “I don’t think there’s anything inherently wrong with single-payer,” he says, but worries the policy is “in danger of becoming a litmus test for some progressive organizations.” Meanwhile, Himes argues, the party is failing to prioritize what should be a central issue for Democrats: “We’re making a terrible mistake right now by telling ourselves we’re talking about jobs and growth, but we’re not.”

Kessler agrees, and criticizes in-vogue progressive policies like universal basic income. “It’s like saying we’ve given up—that there isn’t going to be work for people so let’s buy them off,” he said. “Nobody says ‘I hope I grow up to get a $12,000 UBI.’” Third Way released a report earlier this month urging Democrats to become “the party of jobs”—consistent with the “Better Deal” agenda—and resist “policies perceived as handouts.” The report says the party should be friendlier to business and deemphasize social issues, finding a better “balance” on these subjects. In the meantime, Third Way wants Democrats to get behind universal private pensions and “venture capital funds, seeded by the federal government, for states to invest in local entrepreneurs,” according to the Times. In the face of automation, Kessler says, America needs “a tax code that treats people as well as it treats robots.”

To many Democrats, these types of ideas won’t sound as exciting as Sanders’s bold proposals, and Himes acknowledged as much. “A lot of the ideas that are important to growth would put you to sleep in a second,” he said. “I’m not sure how I can make bridges and airports and resilient power sexy, but I do know that’s critical.... I think it’s a huge challenge, and I’m not sure I know the answer.” But Marshall argues that centrism can offer bold new ideas rather than just tinkering with established policies. “New Democracy is not interested in incrementalism,” he told me, arguing their education policy ideas for public school choice, for example, represent “a bigger structural change than anything the left is proposing now.”

For now, the disagreements between the Democratic Party’s left and centrist wings aren’t playing out in big, public ways (except, of course, online). Strategist Simon Rosenberg noted that Sanders faced no notable Democratic criticism for his single-payer rollout. He said the party is “in evolution” and less clearly divided into two obvious wings. “What I see is a party that’s leaving one era of what it means to be a Democrat,” he said. “I’m not sure that people know exactly what the best way to move forward is.” But Rosenberg argues that many of the party’s rising stars—senators Cory Booker, Kamala Harris, and Chris Murphy, Representative Seth Moulton, California Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom—defy easy categorization on the ideological spectrum. “I think this is going to be a period of experimentation,” he said, “in the early stages of the birth of a new Democratic Party.”

And yet, the left’s influence even on more centrist Democrats is evident. Reflecting on his interview with Clinton, Klein noted that she “lit into parts of Sanders’s [single-payer] plan that she viewed as unrealistic and even politically disastrous. But the health care ideas she emphasized in response—‘to open up Medicare, to open up Medicaid, to do more on prescription drug costs’—reflect the influence Sanders has had on the debate. Clinton is proposing half-measures to single-payer in a way that wasn’t common for Democrats 10 years ago.” What’s more, mainstream Democratic senators and center-left think tanks are beginning to do the same. There certainly will be centrist candidates for president in 2020. “My guess,” Marshall said, “is you’ll see a really crowded field in which you’ll see a bunch of people running as lefty populists but you’ll see people running as pragmatic problem-solvers.” But those moderates may almost certainly be farther left than Hillary Clinton, whose platform was much more progressive than she got credit for.

The overall trend is dismaying to Nick Troiano, executive director of the Centrist Project, which encourages moderate independent candidates to run for office. Asked if he saw any high-profile Democrats staking out an alternative to the ascendant left, he said, “I think everyone’s afraid of their own shadow and really risk adverse to do something new.” Like many centrists, Troiano believes the success of Sanders and Trump in 2016 was about “insurgency and not ideology,” meaning there should be political space for Americans “alienated by democratic socialism on the left and economic nationalism on the right.” (Brookings Institution scholar Bill Galston and Weekly Standard founder Bill Kristol are attempting to build a different kind of “New Center”—one that tackles “immigration, trade, corporate concentration, and the shrinking work force,” according to The Daily Beast.)

The left should acknowledge there are ways in which ideological diversity can be beneficial to Democrats in 2018. “I do think it’s really important for people not to impose purity tests,” Kazin, the leftist Georgetown historian, told me. “You’re not going win in North Dakota with the same politics as in California or Massachusetts.” He agrees there are serious obstacles to selling the country on some of the left’s policy priorities, and says “the Democratic Party is not going to become a hard-core left-wing party unless the rest of the country goes that way.” He added, “Radical change is not easy, and it’s important for people on our side to understand that.”

What centrists should understand, meanwhile, is that much of what they’re warning against isn’t as radical as they’re making it out to be. The two Democratic governors who championed free college this year were a pair of centrist 2020 prospects —New York’s Andrew Cuomo, who got his plan through, and Rhode Island’s Gina Raimondo, whose program got pared down by the state legislature. The universal basic income that Kessler disparages? Clinton nearly included it in her campaign platform, before deciding she couldn’t make the numbers work.

Should these trends trouble centrists, they can take comfort that they’re probably right about this much: The left is shaping the Democrats’ agenda now, but nothing is forever in politics. Parties seesaw ideologically. “Social democracy is more in vogue than normally,” Marshall said, “but these things are cyclical.” And it might not take long to settle the question of whether moving left will broaden Democrats’ appeal—as short as a year, perhaps. “We’re both at a proof of concept point,” he said. “Let’s see how many single-payer advocates win statewide elections in South Carolina and North Carolina.”