Art is always political. Shoe design, ceramics, tapestry: all creative acts are made within historical and political contexts. But artists express their politics in different modes. Some critique indirectly, as in, say, the femininity-satirizing works of Sarah Lucas. But others work much closer to the headlines.

“Wild and Blue” is the first New York solo exhibition for painter Celeste Dupuy-Spencer, whose paintings of bookshelves and people were a Whitney Biennial 2017 highlight. In that show, Dupuy-Spencer’s drawing “Trump Rally (and Some of Them I Assume are Good People)” stood out from her other works for both the timeliness of its content (people in MAGA hats) and its dark humor—Ku Klux Klan hoods become whimsical Caspar-the-Ghost-shapes, the ralliers’ faces distorted cartoonishly.

In this new show, Dupuy-Spencer continues her engagement with the current moment in America. The painting “Love Me, Love Me, Love Me, I’m a Liberal” shows a warped figure obscured by a vase. In one hand she holds a letter with part of the name “Merrill Lynch” visible on it. A letter addressed to GRANDMA lies on the table, near an I SUPPORT NPR mug. The painting works as satire because it is also partly an intimate and traditional table scene. Is this distorted person a type, standing in for Clinton, or a specific person who is sitting at a specific table, by a specific bunch of flowers? Or is this instead just the latest installment of a long tradition of table-paintings, crudely filled in with the symbols (keywords?) of our time?

That ambiguity—between satire and traditional figurative relations—continues in Dupuy-Spencer’s landscapes, which may be the strongest element of the show. “Lake Pontchartrain Causeway” is a large (65 x 50 in.) landscape of the long, long overwater bridge in Louisiana. The road plunges downward in a dynamic curve. To the left and in the sky, storms are bubbling. The painting shows a prosaic stretch of tarmac at the moment before meteorological tension is unleashed, again, on New Orleans.

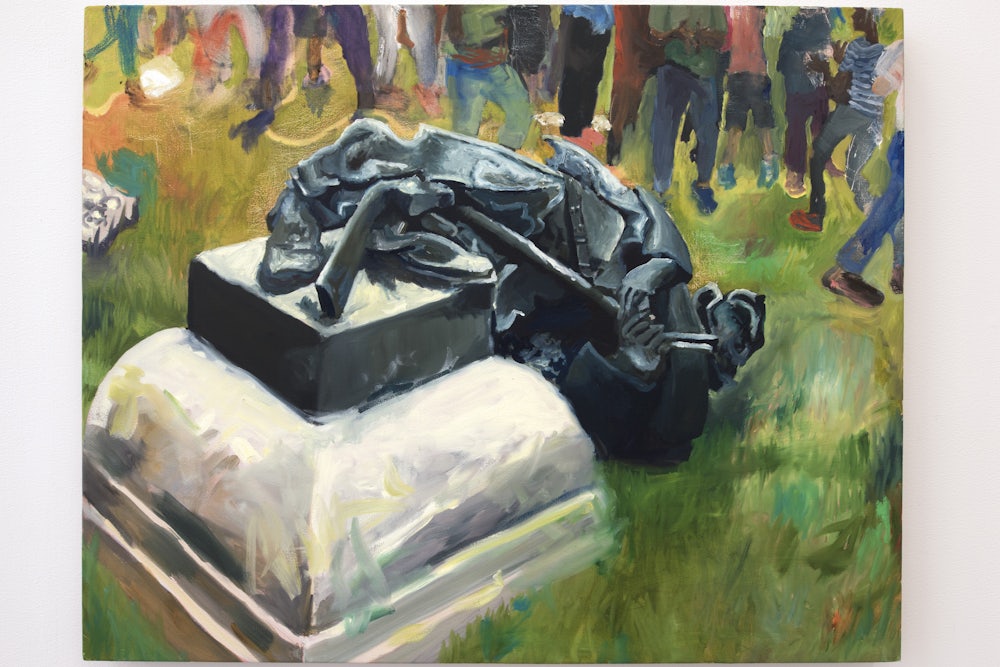

“Durham, August 14, 2017” is a painting of the statue of a Confederate soldier, after its destruction by a North Carolina crowd following the racist violence in Charlottesville, Virginia. Dupuy-Spencer has chosen an angle from which the soldier’s hands are still visible among the whorls of metal. The metal is very flat in color, making the statue seem ersatz, plasticky. By contrast, the crowd of people around it are a host of multicolored and dreamlike legs. In the distribution of technique across this painting, Dupuy-Spencer draws out an experience of this important political object that has otherwise not been part of the public discourse around it. It is ekphrastic, but this artwork also depicts another work of art: in the wreckage of the fallen statue, Dupuy-Spencer sees a monument to search for justice.

Dreams and magic continue in “Not Today Satan,” a painting with a funny title and an interesting subject matter. In the back of a cop car sits a ghoul. On top, a host of goblin-ish figures cavort. One is wearing a gold chain. Just beyond them, a Delacroix horse rolls its eyes in terror. In the front seats the oblivious, blankly-staring human officers drive. At the base of the painting the cop slogan POLICE PROTECT AND SERVE is legible. The juxtaposition of this platitude with the joyful burlesque of demons constitutes a lighthearted, anarchic commentary on police brutality.

Dupuy-Spencer is interested in labelling. In several paintings words are legible, and in some drawings the people (like the country hero George Jones) are in labeled by name or given words to say. This technique lends the effect of a political cartoon to Dupuy-Spencer’s works, which otherwise would exist too much in the abstracted and uncommitted sphere of fine art qua fine art.

It is not possible to walk around this show and get a strong sense of Dupuy-Spencer’s specific political convictions. In an interview with the World Socialist Web Site recently, she said that “Identity politics is the poison of the left,” the “easiest, most narcissistic form of political debate, to only view things from the point of view of one’s personal race or gender.” (Dupuy-Spencer has since stated that these comments do not reflect her position.) Issues of class are lost in these conversations, she said, and in that elision we lose interest in and information on the real people who elected Trump. The working class becomes a scapegoat.

This is not orthodox thought on the left now. But Dupuy-Spencer is without doubt committed to deepening and making more detailed the representation of places and people and material circumstances in America, and for that reason her work is ideologically aligned with the activism of those working in literature, in broadcast, in journalism broadly conceived. In that same interview, she compared her painting Veteran’s Day (2016) and her surrounding project to Picasso’s Guernica in the Spanish Civil War, and “Horace Pippin’s drawings from the front line in WWI.” Like those artists, Dupuy-Spencer sees her own work as a “call to the front line in a revolutionary time.”

Figurative painting, especially the intimate and human works of a painter like this, provides a textured and emotional treatment of political topics. Dupuy-Spencer’s playful approach to our political moment is at the same time deeply serious, because its timeliness makes it urgent. It is also arguably serious in its assertion that painting can be a kind of journalism, and can serve the same purpose.

“Wild and Blue” runs September 7 — October 7, 2017, at Marlborough Contemporary Gallery.

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that the statue of a confederate solider portrayed in “Durham, August 14, 2017” was toppled by a crowd in Charlottesville, Virginia. It was, in fact, toppled by by a North Carolina crowd following the racist violence in Charlottesville, Virginia. This piece has also been updated to reflect Celeste Dupuy-Spencer’s comments on her interview with the World Socialist Web Site.