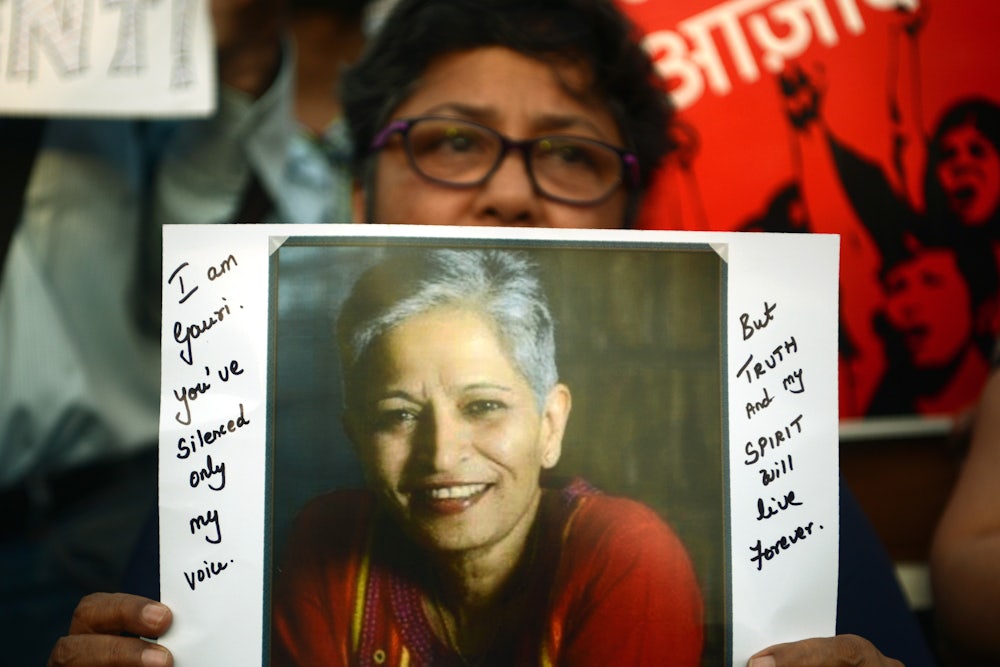

On September 5, the journalist and activist Gauri Lankesh was found slain outside her home in the southern Indian city of Bengaluru, gunned down in cold blood by an unidentified shooter. Lankesh was the editor of an eponymous weekly tabloid, Gauri Lankesh Patrike, that was disseminated in the local Kannada language and known for its feisty left-wing bent. There is ample suspicion that her murder was carried out by those who had long wished to silence her. Lankesh’s lawyer B.T. Venkatesh, who represented her in 15 defamation cases, believes her killing was a sinister and premeditated act by “Hindu terror units.”

Lankesh is just the latest victim in a chilling string of crackdowns on journalists—and dissent more broadly—in the world’s largest democracy. Under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, India has witnessed a surge of threats against those who visibly oppose his Hindu nationalist program. The justice of the mob has been employed to snuff out ideological irritants, and these vigilantes are safe in the knowledge that they are a protected species, licensed to operate with impunity. Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party has injected a toxic communalism into the Indian body politic, creating the space for lynchings and other extra-judicial crimes to occur with alarming frequency.

India’s constitutional values and secular legacy hang in the balance, threatened by those who would turn the country into a theocratic Hindu Rashtra: a state run by and for Hindus, where minorities exist as second-class citizens and free thinking is brutally censured.

Over the past four years, a number of public dissidents have paid a fatal price for resisting growing Hindu extremism. Three prominent secularists were murdered under circumstances similar to Lankesh’s for espousing “anti-establishment” and “anti-Hindu” views.

In 2013, 67-year-old Narendra Dabholkar, a doctor and author committed to debunking miracles and religious superstition, was shot during his morning walk. In February 2015, 81-year-old Govind Pansare, a member of the Communist Party of India who infuriated Hindu chauvinists by de-Brahminizing the narrative of the famous Marathi warrior-king Shivaji, met a similar fate. In August of that year, the scholar M.M. Kalburgi, who had served as the vice chancellor of Kannada University in Hampi and drew ire for speaking against idol worship, was killed.

That justice has yet to be meted out in each case is the bloody backdrop for what happened to Lankesh. These four victims share other important aspects in common. One is that they spoke and wrote in regional languages as they confronted illiberal forces. Right-wing nationalists revel in directing their vitriol toward a liberal, haughty, English-speaking elite, but it is the progressive speaking in his or her native tongue who is most unsettling. As Sidharth Bhatia of The Wire observes, “The ability of these writers and thinkers to reach a wider audience and consequently exercise more influence in the general populace made them very troublesome to their ideological enemies.”

Another commonality relates to the issue of state power. In an op-ed for the National Herald, Soroor Ahmed contends that since the BJP does not have recourse to administrative and police machinery in states it does not rule, zealots have resorted to assassination plots to quash dissident voices in those places. Sure enough, Lankesh and Kalburgi were killed in Congress-controlled Karnataka state, and Dabholkar and Pansare were executed when the Congress-NCP government presided over Maharashtra state.

What sets Lankesh apart from these victims is her ties to India’s embattled media industry. Political parties and individuals with party affiliations have been fast accumulating ideological purchase over the airwaves, with more than a third of news channels under some form of political control. Although heralded as the promised land of journalism with more than 80,000 print publications and around 400 news channels, India’s trajectory on press freedom is worrisome.

In its 2017 rankings that measured journalistic independence, Reporters Without Borders placed India at an ignominious 136 out of 192 countries surveyed. The report states where it sees the danger emerging: “With Hindu nationalists trying to purge all manifestations of ‘anti-national’ thought from the national debate, self-censorship is growing in the mainstream media.” International ombudsman Freedom House also echoed these concerns in its 2017 report. The Committee to Protect Journalists accounts for at least 40 journalists killed in India since 1992, one of the select countries on its “impunity index.”

Earlier this year, non-profit South Asia media watchdog The Hoot reported that, between January 2016 and April 2017, there had been 54 reported attacks on journalists, three instances of TV news channels being banned, 45 internet shutdowns, and 45 sedition cases against individuals and groups. The report also identifies journalists who have been singled out and attacked for engaging in investigative reporting.

And when not threatened with physical reprisals, journalists who dare to criticize the BJP government are duly targeted by online smear campaigns.

The Indian Republic, long underpinned by a postcolonial Nehruvian consensus, is visibly under siege. A new totalizing ethos seeks to supplant the pluralism of Nehru and Gandhi with a monolithic vision of nationhood steeped in the supremacist ideology of Hindutva (“Hindu-ness”). And the terrain where this battle has played out most prominently has been the media: in print and online. The so-called “Saffron brigade”—those cultural warriors mobilized by an emergent Hindutva media ecology—have mounted a backlash against a media and intellectual class tarred as ultra-liberal.

The rise of anti-establishment resentment, anti-PC rhetoric, and the aesthetics of transgressive chic should be familiar to American voters who have followed the emergence of the alt-right. And for a more extreme example of what can happen to a democracy that fosters an antagonistic relationship with the fourth estate, look at President Recep Erdoğan’s Turkey, where over 150 journalists languish in prison along with 13 members of its second-largest parliamentary party; where judges, academics, and civil servants are blacklisted; where restrictions on internet and social media access are imposed; and where media outlets slightly critical of the government are shut down.

In all three cases, a right-wing party driven primarily by communalist politics was pegged as a less corrupt, development-oriented, anti-establishment alternative. In India’s case, the renewal of the virile Hindu subject was instrumental, allowing the BJP to claim that its opponents in the Congress Party were “sickulars” whose opportunistic vote-bank politics came at the expense of the long-oppressed Hindu majority.

There is a strong undercurrent of cultural fascism in Hindu nationalism. As K. Satchidanandan argues, “Hindu cultural nationalism is nationalism shorn of the respect for other identities and cultural differences on the one hand, and of the vision of a cosmopolitan internationalism on the other.” However, for such a movement to succeed, society must contain a pre-existing homogenous bloc with sufficient numerical strength. This is difficult in India’s notoriously diverse amalgam, and so the ideologues of Hindutva have appealed to a primordial Vedic past, prior to the arrival of the Mughals, in a bid to negate the Hindu faith’s plurality and syncretic history.

The founding ideal of the postcolonial Indian state was enshrined in its progressive and secular constitution, but it has always been in tension with more chauvinistic nationalist forces. Today’s BJP relies on a sectarian narrative inspired by M.S. Golwalkar, one of Hindutva’s ideological architects, who wrote in admiration of Nazi ideas of race purity and ethnic cleansing.

Compared to Western varieties of conservatism, theology plays a hegemonic role in Indian conservatism. As a result, the core of Indian nationhood is premised upon the centrality of Hindu religion and values, and any opposition to this tenuous narrative has to be violently stamped out or slapped with charges of sedition. This is why Hindutva’s principal victims—Muslims, Dalits, women—are also those who pose threats to the rigid hierarchical and caste systems it wants to impose.

Gauri Lankesh’s murder is a terrible omen for the country. India is swiftly mutating from a formally secular republic to one that openly nurtures and actively participates in the erasure of those who dare to exercise their constitutional right to dissent. It bodes ill, too, for those countries that believed they had consigned such dangers to the past, recalling Amartya Sen’s rejoinder that the “defeated argument that refuses to be obliterated can remain very alive.”