As someone who has spent a lot of time around self-described anarchists, I often find it hard to understand how some people see them. There’s variation as within every group and ideology, but the anarchists I’ve met tend to distinguish themselves by being thoughtful and even loving. They do a lot of care work, professionally and otherwise. They’re more likely than most to refuse drugs and alcohol. And wherever people circle their A’s, vegetarianism is the norm. Of the dozens or maybe hundreds that I’ve met, I’ve never known one who took risks with other people’s safety just for the sake of it. And yet, when folks hear the term “anarchist” they think Natural Born Killers. They are wrong, but the picture isn’t baseless.

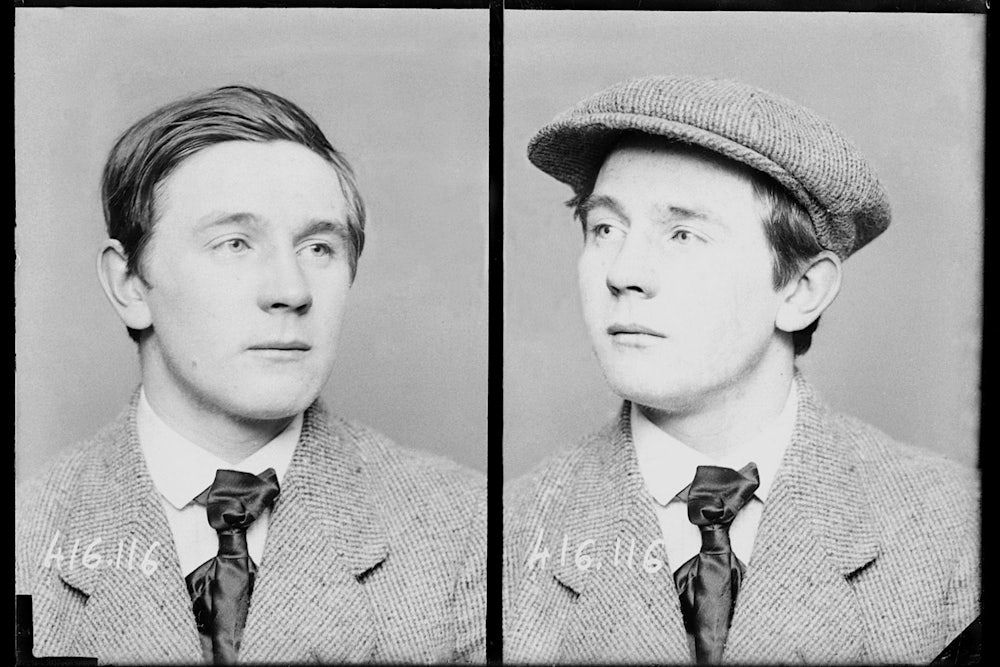

In his book Ballad of The Anarchist Bandits: The Crime Spree That Gripped Belle Epoque Paris, historian John Merriman dives into a vortex of violence that broke out in Paris in the early twentieth century when a network of anarcho-individualists initiated their own mini crime wave. Over a century later, these events still make it hard to imagine anarchism as an overwhelmingly peaceful practice. Merriman’s lens is young anarchist Victor Kibaltchiche (later and more popularly known as Victor Serge), who finds himself an accomplice in armed robbery and murder. Despite the branding, Ballad is perhaps best described as a book-length explanation of how the famous prisoner Serge came to serve his first sentence: anarchism.

Ballad takes place in and around 1911, 40 years after the suppression of the Paris Commune (the subject of Merriman’s previous book, Massacre). The rich won the battle, and they enjoyed the spoils. Paris of the time seemed belle in retrospect compared to the decades that would follow, but it was deeply unequal, and the haves enjoyed their blurry paintings and stimulating salons at the poor’s expense. Motorcars drove by starving people—as they would continue to do into the indeterminate future—for the first time. The dramatic juxtaposition of wealth and progress with absolute deprivation yielded, in some, a moral crisis. If this was law, then what good was the law? Merriman’s centers around the tension between two kinds of anarchists. On one side are Kibaltchiche and his editorial and romantic partner Rirette Maîtrejean; on the other was The Bonnot Gang.

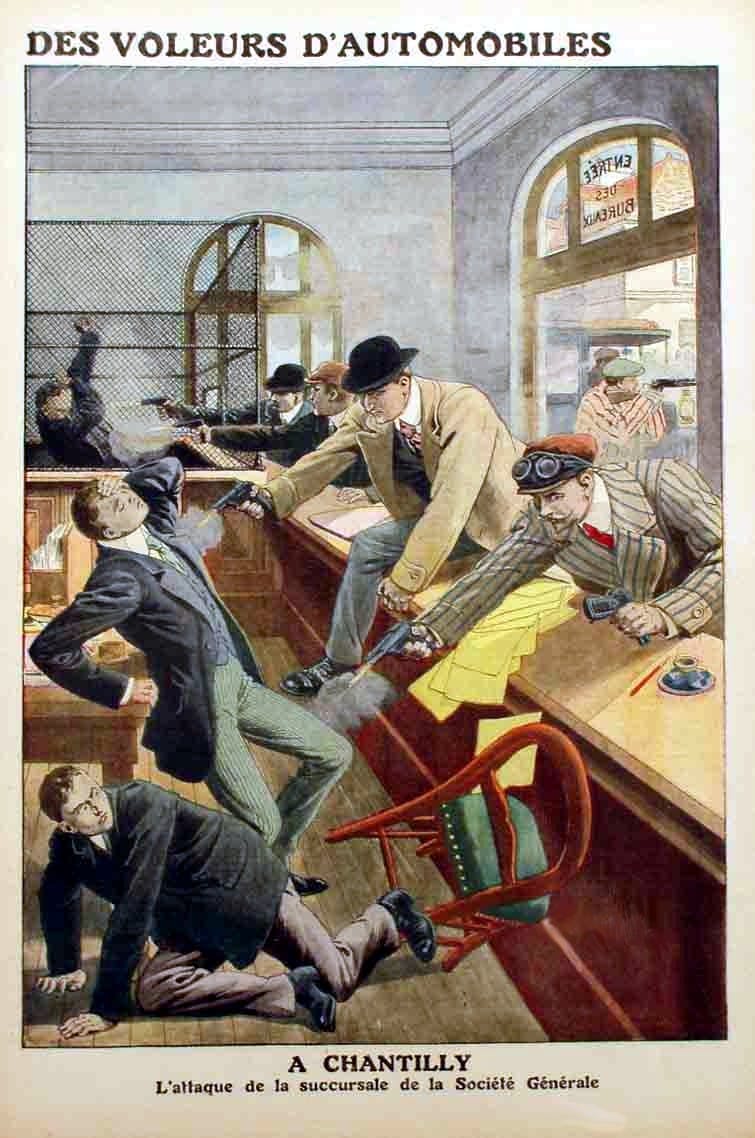

Kibaltchiche and Maîtrejean were proud anarchists—rejecting the law of the rich, agitating for revolution, and attempting to live in harmony and generosity with the world around them—but the “illegalists” made it impossible for any anarchists to appear benign. Illegalists saw and used lawbreaking as a means (to fund their activities) and as an end. While Kibaltchiche and Maîtrejean thought of the labor movement as a way forward, others (including Kibaltchiche’s boyhood friend and Gang member Raymond Callemin) liked bank robberies, counterfeiting, and shooting cops. As the modern urban police were coming into being (with their machine guns and squad cars) so were the modern urban criminals (with their repeating rifles and getaway cars). While the state attempted to elevate a new regime of law and order, illegalists sought to pull it back down to earth. Every spectacular heist or shootout was a lesson for the public in the law’s impotence and absurdity.

“The Bonnot Gang” is a historical misnomer. Jules Bonnot was the one who killed Deputy Security Chief Louis Jouin and he had the most dramatic shootout death, but Merriman’s research suggests if there was a leader of their criminal band, it was probably Octave Garnier. Nor were they really a gang per se, so much as an ideologico-criminal milieu—a bunch of guys who read Nietzsche and Max Stirner and committed crimes. Emboldened by the egoistic philosophy, they had no compunction about shooting and killing people if that was the fastest way to get what they wanted, and not just class enemies. Merriman doesn’t have much interest in moralizing about their violence; he plays up the theatricality of it all instead. No doubt other historians have been more blasé about larger body counts, but the author’s excitement and levity makes the whole project a bit unseemly. Murdering people who just happen to be in the way—as the Gang did—is made only slightly more charming with an olde tyme color palette.

The illegalists’ crimes attracted the sympathy of some communist anarchists—Kibaltchiche would become a Bolshevik, once that presented itself as an option—who were not opposed in principle to stealing or breaking laws. Despite the threats of police infiltration, anarchist communities tend to be welcoming to outsiders, especially compared to the residents of bourgeois neighborhoods. When the final bill came due for the illegalists’ Paris crime spree, the authorities didn’t differentiate between factions. Asked by the authorities if they had sheltered criminals, members of the anarchist milieu invoked one of their many values: Anarchists gave shelter without asking questions, including for names. In Merriman’s telling, this was more or less true depending on the situation. Because though the communists fought with the illegalists in leftist publications and in person, they refused to denounce them to the police, the courts, or the bourgeois press.

In their own papers, anarchist communists varied in their response to illegalist crimes. After an armed and reckless bank robbery (during the getaway Callemin shot himself in the arm), Le Temps Nouveaux called the acts “purely and simply bourgeois,” reflecting the “principles of egotistical individualism”—not anarchist at all. Le Libertaire simply ignored it. But Kibaltchiche in L’Anarchie wrote that if the bandits were wolves, then he was “with the wolves, the wolves who are hunted, being starved out, and tracked, but who can bite back!” Kibaltchiche throughout his life was with the left wing of the left wing wherever he found himself, and he was more careful defining his differences with the illegalists than his sympathies, which were deep and affective.

When forced to choose by the courts between illeglists and the police, the banks, and their collaborators in the public, Kibaltchiche and Maîtrejean were clear and strong. Maîtrejean stood on her anarchist principles, denying that she was in practice the managing director of L’Anarchie, claiming to be just another comrade. The court found her testimony compelling, and she was acquitted as an accessory to the crimes. Kibaltchiche complained “You refuse to distinguish between L’Anarchie of Romainville and that of rue Fessart,” which probably makes as much sense to the uninformed reader as it did to the jury. He got five years, in part for refusing to testify against others. His illegalist co-defendants were sentenced to death.

The story of the Bonnot Gang, ultimately, isn’t good for much. By outgunning and outdriving the police the illegalists hurried the development of the modern security state, but that’s a chicken-and-egg situation at best. Kibaltchiche’s sentence coincided with much of World War I, and he was probably safer inside than out. Ballad is an action story that would fit in just fine on any number of cable networks, but as a historical event it lacks a certain weight. Merriman doesn’t draw many contemporary parallels, and the best he can come up with in terms of a lesson is that class divisions cause crime. Fair enough, but hardly revelatory. At the end of the day, historical action entertainment is the other side of the illegalist coin, where the violence is once again a means and an end.