Midway through Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold, Griffin Dunne, the documentary’s director and Didion’s nephew, asks what interested her in the “Central Park Five,” the falsely accused and wrongly convicted young men alleged to have beaten and raped a white woman in Central Park in the late 1980s. “Oh,” she replies, “it was just a natural story for me. Everything about that story was a lie.” In a queasy projection of past onto present, Dunne then cuts to Robert Silvers, the late editor of The New York Review of Books, recalling Didion’s immediate suspicion of pat narratives of good and evil; to Ed Koch crowing “to understand is to forgive; I don’t want to understand what motivates someone to engage in this kind of horror”; to Donald Trump, whose first foray into politics was to call for these “thugs to fry,” as the Sunday cover of the New York Post indelicately put it in a headline. This collapse of the timeline is directorial artifice, of course, but it’s also the sort of mingling of hindsight and foresight that characterizes a decent prophet. Didion wouldn’t like to be called a prophet, of course, so I’ll just call it uncanny.

But, because The Center Will Not Hold is a documentary, it’s also worth returning to what Didion actually wrote about the case in her essay “Sentimental Journeys”:

The imposition of a sentimental, or false, narrative on the disparate and often random experience that constitutes the life of a city or a country means, necessarily, that much of what happens in that city or country will be rendered merely illustrative, a series of set pieces, or performance opportunities.

The life of a city or a country, or just a life. It’s difficult, watching this film—to be fair, almost any documentary—without that nagging phrase tickling the back of your brain: merely illustrative. Didion long ago transcended the modest space our culture reserves for writers to become a kind of living metonym for the whole period of postwar American history, from the dark-underbellied triumphalism of the California boom through the seemingly endless succession of social crack-ups that have defined this country ever since. And so her life would tempt anyone into a schematic history in which the conditions of the present are back-projected to construct a story about the inevitability of the past. The “often random experience” comes to seem not random at all, but necessary and predetermined. The publication of each book, the death of each relative: constructed as if by an author.

Dunne, fortunately, is cannier than that, even if he can’t entirely avoid the undertow of narrative’s necessities. Well, this is a movie, after all. It’s a fairly conventional documentary. The archival footage—grainy and often quite lovely—occurs exactly when you expect it to occur; the pans over still photos are the same as in every other documentary; the talking heads, who are mostly friends, family, and collaborators, are a cut above most talking heads, but they are still sitting in comfortable studies, surrounded by books, talking. It’s all very stolidly interesting and all a little bit rote, in part because none of them—not Robert Silvers, not Vanessa Redgrave, not David Hare—are half as interesting as Didion herself.

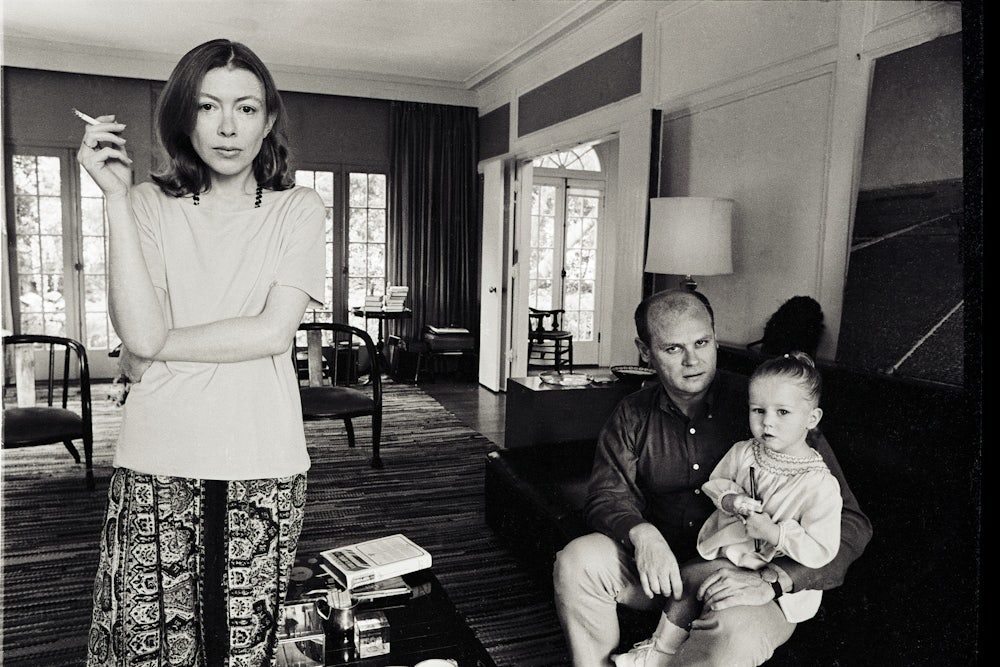

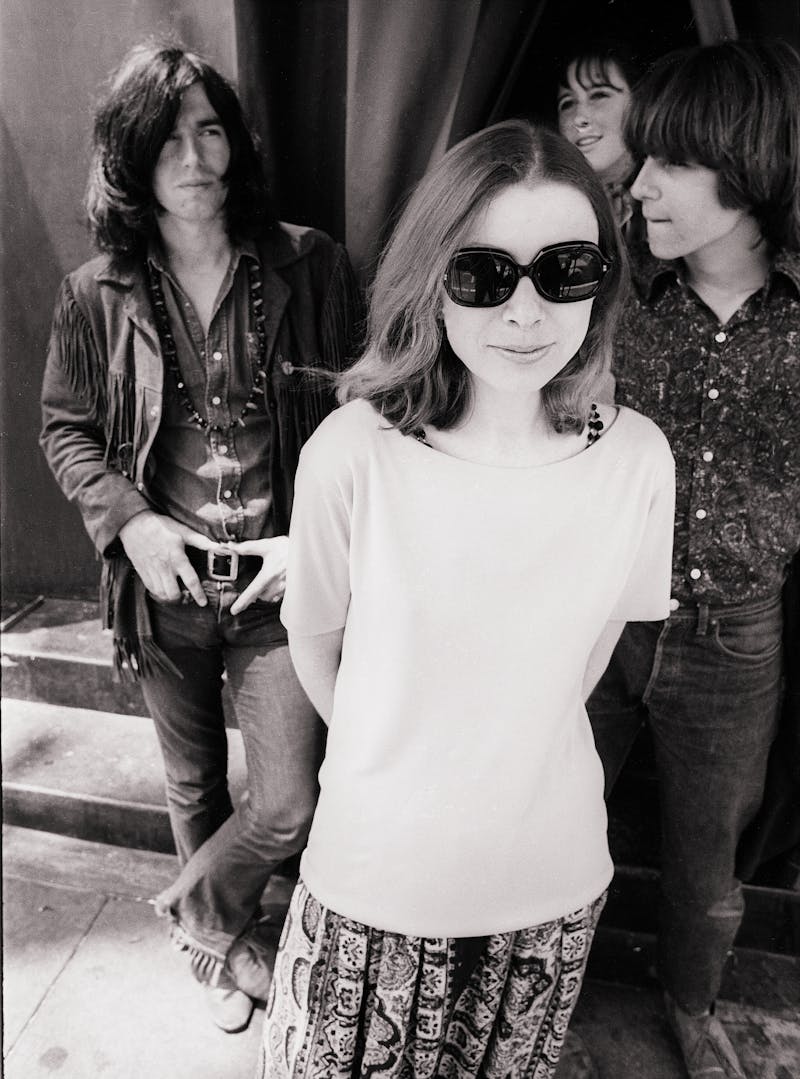

It is Joan Didion who saves the film from becoming a well-meaning but unremarkable enterprise, and I give Dunne tremendous credit for dragging her back from our stylish efforts to turn her into another dull celebrity, a slim commodity with big black glasses gazing out from a corny fashion ad. He permits her to be as she actually is, very old, a woman—an actual woman—no longer at the height of her powers. This is a service, because we’ve created a cult of genius that makes genius transcendent of our humanity rather than fundamental to it, undimmed until we croak out “More light!” at our dying moment. Poor Goethe probably just wanted another candle, and Joan Didion’s lipstick is messy. Her gestures are a little disconnected from her sentences. She is frail.

In these moments, the film becomes something much closer to what Didion herself achieved in The Year of Magical Thinking and, to a lesser but still notable degree, in Blue Nights; it penetrates past the ersatz character, the persona Didion wrote herself into across four decades, and reveals the underlying person, the “often random experience,” as bewildered as any of us, as often alone. She’s said in the past—particularly of coming rather late to explicitly political writing—that she writes when she wants to understand something, and now that she’s no longer writing as she once did, she seems at a very recognizable loss.

At the same time, she’s much more voluble in this film than in any interview I’ve seen. There is, for example, an excruciating C-Span program from years ago—shown in a clip in the documentary, but worth watching in its entirety—in which, while she’s never boring, she seems, at every moment, to want nothing more than to flee the room. Here, her affection for Dunne is evident. The best scene in the entire movie is a throwaway moment in which, like any good younger nephew at the house of his elderly aunt, Dunne pokes into her refrigerator and asks her who’s making her so much soup. It is, she tells him, ice cream. That this brief bit didn’t end up on the cutting room floor, that we’re permitted so candid, if brief, a view, feels like a little miracle until you consider that a film is at least as intentional as an essay and remember that it must have been Dunne himself who left it in.

Others will probably comment on Didion’s willingness to say openly what she only ever hinted at and what has fueled book-chat gossip since Magical Thinking came out: that her husband had a temper, and that both he and their daughter drank too much. To me, that speculation always seemed prurient; we knew what we needed to know, and her writing pointed us in more interesting directions. Still, there’s something extraordinary about her forthrightness here, something remarkable about her having to tilt the photo album and lean in close to see the pictures. At the end of the film, Dunne’s camera follows her through her apartment as, in voice-over, she reads from “On Keeping a Notebook.” “Remember what it was to be me,” she says, “that is always the point.”

In fact, it was always hard to know what it was to be Joan Didion; ever since Montaigne said he would make himself the subject of his own book, writers have been hiding their selves in characters, in plain sight. But then, Didion says something else in the very next paragraph of that same essay:

Only the very young and the very old may recount their dreams at breakfast, dwell upon self, interrupt with memories of beach picnics and favorite Liberty lawn dresses and the rainbow trout in a creek near Colorado Springs. The rest of us are expected, rightly, to affect absorption in other people’s favorite dresses, other people’s trout.

The great criticism of Didion was that she was all affect, all style; it was never true, but like so many false critiques, it had an element of truth. And now we have this. As a pure piece of cinema, Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold is sometimes beautiful, mostly workmanlike. As a document of the very old recounting her dreams at breakfast, it’s a bit of a marvel.