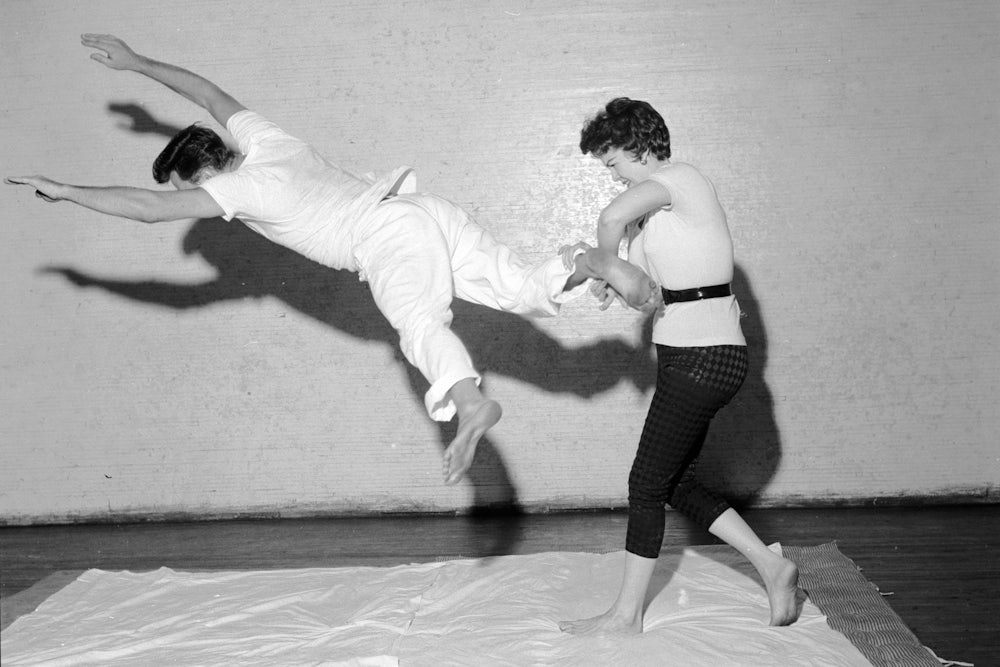

One June day in New York City, Lillian Ellis was home alone with her younger siblings when a friend of her father came calling. Who knows why? Perhaps he meant to meet her father and was surprised to find Lillian alone, or perhaps he intended to rape and murder her before he walked in. All we know now is that he tried to strangle Lillian and broke a vase over her head, fracturing her skull, though she still managed to fight him off for half an hour, and lived. The year was 1920, and Lillian was twelve. In the local paper, her survival was credited to her knowledge of jiu-jitsu.

As Wendy L. Rouse details in Her Own Hero: The Origins of The Women’s Self-Defense Movement, such stories were becoming almost common at the dawn of the twentieth century. A rise in women’s employment and social independence coincided with increased immigration, which led to a confluence of racist and sexist anxieties that left white upper and middle class Americans with a discomfiting awareness of their bodily vulnerability. With Teddy Roosevelt, a devotee of muscular feats, serving as president, a newly physical, newly public life was promoted, and urban media outlets obligingly documented the remarkable confrontations that ensued—many of them involving women beating off their would-be attackers.

The individual triumphs described in Her Own Hero are the sort of satisfying stories that would go hugely viral today. One Washington heiress hated Roosevelt so much that she committed to replicating every physical feat the president bragged about, including “riding a relay of fast horses several hundred miles,” just to spite him. In 1905 Harlem, while an impromptu gathering of onlookers cheered, a 95-pound Japanese American woman downed an assailant, twice. (The man was later revealed to be “a prominent athlete and boxer,” and a court sided in her favor against him.) A year later, also in New York, an 18-year-old punched a man several times in the face after he followed her on the street, and in Nebraska, in 1913, a woman stabbed a man with a hat pin because he pinched her arm and called her “some cute chicken.”

It’s curious to read stories like this and feel something akin to envy, but these sorts of displays aren’t as common today—I can only dream of waking up tomorrow morning to read about a petite woman on the sidewalk throwing a man into a rack of Citibikes. But aside from these flares of highly physical girl power, Her Own Hero’s century-old moment looks a lot like our own. For instance, the era’s intense public and official fixation on the alleged threats posed by immigrants and men of color belied the fact that “native-born Anglo men were the primary perpetrators of harassment and violence against women on the streets.” Unremarked upon by most newspapers and politicians was the fact that the workplace was far more dangerous for women, with their own homes more dangerous still. In 1905 Chicago, sixty-seven percent of recorded female murder victims were killed at home or at work. (Fast forward to 2015: Homicide was the second most common cause of death for women in the workplace across the United States.) Then as now, women were most at risk of harm from men they knew. Just ask little Lillian with the fractured skull and fingernails full of her family friend’s skin.

But encouragingly, Her Own Hero testifies to the instability of such noxious brews of chauvinism and xenophobia. One can only harbor so many paranoias before they begin to cannibalize each other. While “Yellow Peril” hysteria was so virulent in the early 1900s that Japanese were denied the right to own land in California, and later altogether banned from immigrating into the U.S., the fetishization of jiu-jitsu left racist whites in a tricky place; the Japanese were hated, but a Japanese martial art was thought to be enviably lethal. Meanwhile, the fiction of the prevalence of foreign or black street assailants positioned respectable white women as in urgent need of protection, and they could not be accompanied by men at all times. What’s a white man to do if he wants to keep his wife subordinate but also safe from violation? What’s he to do if he believes Japanese martial arts are “dishonorable,” but more effective than fist fighting? Concessions must be made and rationalizations devised. More and more, husbands and fathers sent the women in their families to learn jiu-jitsu. As one San Francisco editor wrote in 1905: “If jiu-jitsu is impregnable against our old attack, and our enemy knows it ... we too, shall learn the new way, regretfully of course.”

Similarly, women in the late 1800s and early 1900s sold female athletics as “a great safeguard against immorality,” and as they gained muscle, they used the ensuing sexualization of their active bodies as cover—#strongisthenewskinny for the pre-Instagram set. “A movement for women’s self-defense was born in this climate of inflated anxiety and fear,” Rouse writes. But because women’s attackers were most likely to be native-born white men, “an undercurrent of discontent” was revealed. That white women were no longer perpetually vulnerable to white men, that they were, in fact, increasingly capable of resisting assault with their own violence, created what Rouse calls “a fissure in white racial solidarity.” “Men in society would be surprised to know how many of the graceful, charming women they know and meet at social functions could take them on with regulation boxing gloves and make dummies of them in a couple of rounds,” wrote a San Francisco reporter of the trend in 1913. Good. Surprise is a weapon, too.

A century into the future, it still alarms men when women “fight back.” This much is evidenced by recent weeks’ furor over high-profile men’s downfalls after sexual assault allegations, with the resultant suggestions that men not be alone with female colleagues and hand-wringing about “witch hunts.” Harvey Weinstein is in hiding in one of his several homes and Louis C.K. has issued a mea culpa confirming his long-rumored assaults, but there’s no lasting sense of justice or peace. Instead, it feels this is the greatest response our sad culture will allow; a handful of predominantly white and sometimes famous people may make public their experiences of sexual assault, and one accused man may endure condemnation and be removed from his professional post after decades of influence, having already amassed millions. This is not a systematic effort but a visceral social reaction, with limited scope and power, however mighty and righteous it may feel as it unfolds in real time.

This was the world of the early twentieth-century women depicted in Her Own Hero, too. “Horror stories” of stranger danger served to “regulate the movement and behavior of women,” and workplace harassment was rampant, as were victim-blaming, and outright denial that a harassment problem existed. Flashes of justice, or at least punishment, or at least successful self-advocacy, are good; they are an improvement upon the status quo even if not a perfect correction to the same. And these are not only moments of cathartic comeuppance; they are evidence of cracks in the system. “If you could be forced to stand everlasting insults that a woman is, you could understand,” one Oakland woman told a male reporter regarding her choice to punch a man on the face after he followed her and grabbed her arm on the street in 1905. “I have waited for too long for some bystander to take up the fight for me, but as no one ever volunteered, I was compelled to assert my rights.”

Still, this recourse was not available to all women. The abusive experiences of working class and/or black women were ignored even as the “lower classes” were cited as the only parties for whom uncouth and violent behavior was an issue. Meanwhile, rich white women were esteemed to be so fragile that sometimes a man would be fined for simply making a vulgar statement—though not if he were the plaintiff’s husband, father, or boss. That jiu-jitsu and other forms of women’s self defense have only been accessible to privileged women—that historically, only white and wealthy women have been permitted to resist (some) molestation—necessarily makes our delight in the spectacle of women beating off offending men a partial and compromised one. The early women’s self defense movement was not a moment of intersectional feminism or rigorous critical engagement with structures of power. It was about upper class white women feeling empowered to remove their white gloves.

The concept that any women could be equal citizens, entitled to share public spaces and enjoy freedom of movement, was still very new. (New enough, in fact, that the women who were quickest to embrace it were identified as “New Women.”) “The radical suggestion that women were capable of serving as their own protectors both emerged from and was influenced by larger campaigns for women’s rights,” Rouse explains, noting that even women who didn’t study or practice self-defense, or identify as suffragettes, were still affected by public discussions of each. Self-defense may have at first seemed utilitarian within the boundaries of the status quo; women are vulnerable and (some) women are valuable, therefore women must be able to preserve themselves, or so the logic went. But the inherent radicalism of this idea was unavoidable. It upended the gender narrative of who relied on whom, and why.

Those weren’t the only scales falling. For the first time, suffragists—who were primarily white and upper class—encountered police brutality and abuse of all sorts from male strangers, and it left them changed. Or as Rouse puts it, “encounters with violence challenged American suffragists to reconceptualize their worldview.... Many American suffragists realized that policemen and male bystanders did not and would not protect them.” American activists were also further warned by the plight of their sisters overseas. After being force-fed approximately 20 times during her imprisonment, English suffragette Alison Neilans declared, “I went in a militant, but I am coming out a raging fire.” Another variation on this theme came from Eunice Murray in the wake of a brutal clash in Scotland. “When I watched a policeman fell a girl to the ground and kick her across the platform,” Murray wrote, “my only regret was that I had no weapon with which to strike.”

It risks redundancy

to refer to a women’s self-defense movement since “self-defense” is

rarely suggested to men. Men are assumed to be both nearly

invulnerable and, innately, always on the offensive. What men defend rather

than their bodies is their good name or their women, which are so often one and

the same. But in the words of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, “every young girl should

be taught the use of firearms and always carry a small pistol for her defense ... whenever she is in danger of meeting her natural protector.” Her

Own Hero is a thorough and fascinating examination of the eruption of one

important insight into public American life: Women can successfully use force

against those who are assumed to be more powerful. And more and more, it

appears, we should.