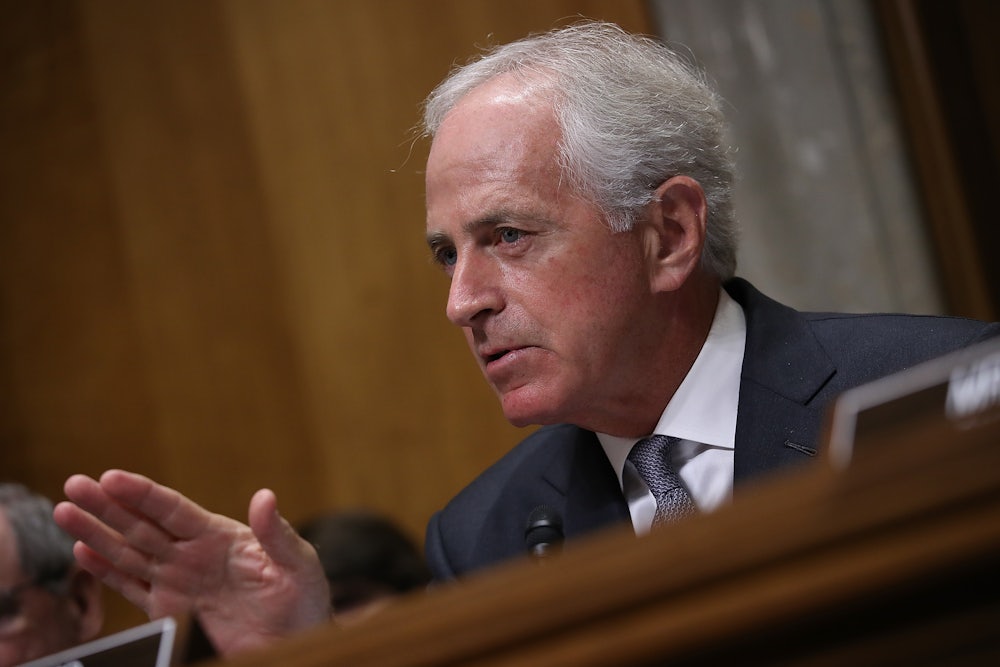

While all eyes were on Jeff Sessions on Tuesday as he testified before the Senate Intelligence Committee on the Trump campaign’s connections to the Kremlin, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee held a long overdue hearing of their own to discuss the president’s authority to launch a nuclear war against North Korea. Chaired by Bob Corker, a Republican and outspoken critic of Trump, the hearing featured testimony from a panel of experts. It was the first time the committee has examined the president’s nuclear powers since 1976.

Senators from both parties raised concerns about the decision-making process by which the U.S. would launch a preemptive nuclear strike. They were particularly interested in which government body—the executive branch or Congress—would have the legal authority to order it. Senator Ed Markey, a Democrat from Massachusetts, in January introduced legislation that would prohibit the president from conducting a “first-use nuclear strike,” or a nuclear strike without provocation from another foreign power, without a congressional declaration of war. His bill has been stalled in the Republican-led Senate.

Some of this confusion, however, is deliberate—and all three members of the panel said they would be wary of any legislative changes to the process. Under the United States’s longstanding policy of “calculated ambiguity,” other foreign powers would, in theory, be deterred from attacking the U.S. for fear that it would retaliate with a nuclear strike. Marco Rubio pointed to an example of this policy during the Gulf War, when then-Secretary of State James Baker signaled to Baghdad that if Saddam Hussein or his armed forces used biological weapons against American forces, it would trigger nuclear retaliation.

These merits aside, a policy of deliberate ambiguity does little to assure Americans that Donald Trump could not launch a nuke “just as easily as he can use his Twitter account,” as Markey put it. And Trump has not exactly given voters confidence that he will handle the nuclear codes responsibly. In August, he threatened North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un with “fire and fury like the world has never seen.” Just this week, as the president wrapped his twelve-day tour of Asia, he called Kim “short and fat.” Trump was also criticized for discussing possible responses to North Korea’s nuclear ballistic missile testing on a crowded terrace at Mar-a-Lago in February—the same night an aide, better known now as “Rick the Man,” was photographed with the nuclear football in what became a viral photo.

Brian McKeon, a former Defense Department official, cautioned against changing the laws to accommodate Trump. “If we were to change the decision-making process in some way because of a distrust for this president, I think that would be an unfortunate precedent for future presidents,” he said.

The panelists also insisted that even decisions during an imminent attack would not be made by the president alone, but rather in consultation with generals and legal advisers, and then carried out by others, who would closely assess the legality of any nuclear order. “The president by himself cannot push a button and cause missiles to fly. He can only give an authenticated order which others would follow and then cause missiles to fly,” one panelist said. Ed Markey did not seem reassured.