On August 9, 1969, the New Republic’s editor in chief Win McCormack was partying with four of his friends in Santa Barbara, California. Earlier that day, reports of a strange and grisly murder had filled the news, the details now famous: the Bel-Air mansion, the pregnant wife of a renowned director stabbed to death, the word “pig” written out in the victim’s blood. As dusk fell, one of McCormack’s friends dove into a fear-driven fantasy of the murders, imagining that they would be the next victims.

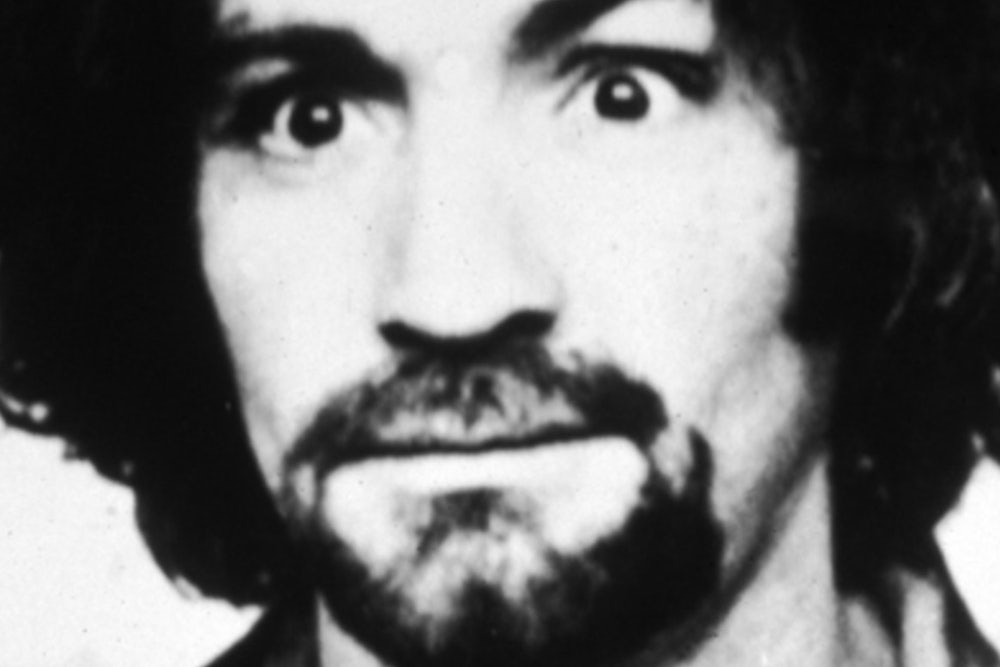

Nearly five decades later, Charles Manson is dead at 83 of natural causes. He died in a hospital, serving a life sentence without parole. His legacy is of entrapping young middle-class women in his cult, and directing them to commit high-profile murders in California. He wanted Helter Skelter, a new world order, to culminate in cataclysm.

In the mid-1980s, McCormack spoke with a former member of the Manson clan, referred to here as “Juanita,” who managed to escape the cult shortly before it orchestrated the murders. In Juanita’s eyes, Manson was both the devil and a reincarnation of Jesus Christ. To Manson himself, there was no difference between the two.

Juanita: [Charles Manson] was not particularly big—probably five-two. Really wiry, real agile. Almost leprechaunish in some ways, with a quick wit. There was a real playful quality about him, an endearing quality about him. He could be very much the little boy, and he showed a vulnerable side that really got you engaged in taking care of him.

Win McCormack: How did he show his vulnerable side?

J: I remember one time—this was at Spahn’s [Movie Ranch near Los Angeles] and it was even very possibly that same night I gave him all my money. There were kittens all over the place. The mother cat had stopped cleaning up after them. They had messed in the kitchen. And Charlie got down on his hands and knees and cleaned the kitchen floor. He cleaned up after the kittens. He picked them up and put them inside his shirt and went and sat by the fire and warmed the kittens and played mother cat. I remember him looking up and saying, “I now understand the pain of too much tenderness, because it hurts not to hug them. But if I were to hug them I would hurt them.” It was those kinds of things. He showed himself or acted like a very, very gentle man that would never hurt anything.

WM: You say you gave him all your money?

J: It was amazing how quickly Charlie read me. He seemed to know all the right buttons to push. Within a month I’d signed over my camper and something like a sixteen-thousand-dollar trust fund, which in 1968 wasn’t small potatoes.

WM: How did he get you to do that?

J: That’s a question I’ve asked myself many times. Some of it was drug-induced, I’m sure. I can remember the night that I told him he could have the money. That day, we started early dropping acid and doing all those kinds of wonderful things. He had been telling me that the thing that stood between me and total peace of mind and heart was Daddy’s money—I was not going to be free of Daddy until I got free of Daddy’s money. Charlie started [saying] that I was my father’s ego. And I remember thinking, That doesn’t make any sense to me. Then later I convinced myself that it probably was [right], because Charlie was always right. Charlie never openly said that he was the reincarnation of Jesus Christ, but if he didn’t say it, he sure to hell implied it. He would say things about having flashbacks about having the nails driven in through his wrists. He said, “The nails weren’t put in my palms, they were put into my wrists.” And, “They always lie to us. Everything’s 180 degrees from the way they told you it was. And there is no difference between Jesus and the devil.”

WM: What if you’d been there? What if you hadn’t been deprogrammed? Do you think that you would have been involved in the murders?

J: My fear is that if I were there I’d be in jail now too. Because I pretty well did whatever he told me to do. I mean, for me to walk forty miles, as I did one time—I had blisters on the soles of my feet that were two and a half inches in diameter ... because Charlie wanted me to go somewhere and I didn’t have a car, so I walked. The basic programming was that you had to die to be freed anyway, so death was not something to be afraid of. That we were all members of one greater consciousness. But the other thing was that if Charlie said, “Jump,” my only question would be: “How high?

Read the entire interview, first published in Tin House in 2007, here.