The sickening spectacle of the Senate, at nearly 2:00 am Saturday morning, passing a bill on essentially party lines, the full contents of which almost none of them knew, its assumptions about how much it would increase the U.S. debt based on sheer fantasy, its cynical abandonment of Republicans’ supposed concern about deficits, its dimly understood sweeping policy implications, its likely trove of potential scandals in the form of special provisions for particular interests or individuals, represented the nadir of the legislative process. The one Republican senator who went against his party, Bob Corker of Tennessee (who as the world knows won’t run again), objected particularly to the bill’s fiscal implications—increasing the debt by at least $1 trillion—and for his efforts to get that solved was considered by his Republican colleagues a major pain. (The current debt is just over $20 trillion, the highest it’s ever been; and this was one of the highest increases in the debt.) In the end, Majority Leader Mitch McConnell gave enough away to holdouts to get the bill passed without Corker’s vote.

In what Wall Street Journal reporters described as “a blizzard of last-minute deals,” a tax break corporations love was accidentally repealed. Frenzied lobbyists, working behind the scenes, played a probably unprecedented role in this legislation, and knew what was in the tax bill before the senators did. Senators who held out their final votes put on a show of struggling “to get to yes” if they could have just one more change, and some pronounced themselves satisfied with less than solid pledges from McConnell and other Republican leaders.

The pressure on McConnell and other Republicans to produce a bill couldn’t have been more intense. Major donors, fed up with the Republicans’ failure to repeal Obamacare or accomplish any other significant legislation, threatened to close their checkbooks as they faced the possibility that the party, led by an unpopular president, was headed into the 2018 midterm elections with none of their legislative dreams fulfilled. Furthermore, the president was facing the major embarrassment of having zero legislative achievements in his first year, traditionally the time a new president gets the most done. Donor pressure helps explain the apparent ease with which the Republicans gave most of the rewards of the bill to the wealthiest 5 percent and abandoned their base. Trump, the populist nouveaux, would have to keep his base loyal by feeding them gimcracks about kneeling (black) NFL players and “crooked Hillary Clinton.” In backing the House and Senate tax bills, Trump, who has set great store by at least appearing to remain faithful to his campaign promises when it came to the Iran nuclear deal, the Paris climate accord, and pushing for the wall, readily broke his promises that the rich wouldn’t get a tax cut and that his cuts wouldn’t increase the deficit.

Perhaps some of the base would be beguiled at first by the idea that they are to receive a tax cut, as the president and numerous TV ads keep telling them—even if it is a paltry one compared to the boons to the very, very rich. In addition to significant income tax cuts, the pending legislation was to give them such presents as a great reduction in (Senate bill) or elimination of (House bill) the estate tax (so that people like, say, Donald Trump can pass on a great deal more money to his children); elimination of the alternative minimum tax, which Trump was particularly eager for; and a tax break for private plane owners. Perhaps the Trump base would remain unaware that their tax cut would end in 2025 and then transmogrify into a tax increase. By contrast, the deep cut in corporate tax rates—the centerpiece of the bill as far as the Republicans are concerned—would remain permanent. The Senate’s tax bill would repeal provisions many middle-class and upper-middle-class families have come to rely on, such as deductions for medical expenses and for state and local taxes. The realpolitik behind the elimination of the credit for state and local taxes is that this will primarily affect residents of high-tax states that vote Democratic. This would also put the squeeze on funds for local services, such as public education and infrastructure repairs. In the mere three days devoted to the Senate’s deliberation on such significant and complex legislation, what started out weighted on the side of the wealthiest taxpayers became more so.

Behind the whole exercise lay the Ayn Randian philosophy that has inhabited the mind of House Speaker Paul Ryan for years and like views shared by conservative Republicans, who now dominate the congressional Republican Party: the goal of reducing taxes and then claiming that this necessitated the reduction or elimination of Medicare, Medicaid, and other welfare programs that they see as fostering “dependency” on government. (Such programs also lend political strength to the political party that supports them.)

As a way of taking care of some unfinished business and also saving some money, the Senate bill also repealed Obamacare’s provision requiring that people buy health insurance or pay a fine—the individual mandate that provides the spine of the program. The elimination of the individual mandate not only struck a blow at Obamacare, but also provided the tax writers with $300 billion. This was not to be put toward deficit reduction, but to be spent on the reduction in corporate tax rates and other bonuses for the very wealthy. (The money saved would have gone for federal subsidies for those who couldn’t afford the insurance.) It’s estimated that if this is in the final bill, about thirteen million people will lose their health insurance.

The GOP’s solution to the increase in the debt that the Senate and House bills produced was to essentially pretend that it didn’t exist. Assertion supplanted policy. As they’ve done before—going back at least to the budget director David Stockman’s “Rosy Scenario” in the Reagan administration—the Republicans resorted to fanciful assumptions about the economic growth that the tax cuts would produce. McConnell stated, “I’m totally confident this is a revenue-neutral bill,” adding for good measure, “I think it’s going to be a revenue producer.” There’s no credible analysis behind such claims.

It’s not at all novel in the course of a debate on certain kinds of bills for a member of Congress in either chamber to hold up a thick sheaf of paper, angrily denouncing its size. There are reasons for these Brobdingnagian bills: It’s been a while since Congress has been able to pass individual appropriations bills that are supposed to be considered by individual committees and thus be subjected to somewhat extensive consideration and expertise; funding the federal government to keep it functioning is one of the Congress’s fundamental jobs. So it has resorted to omnibus legislation providing funds for the entire federal government, the legislation often in disarray. (I can recall a member of the House indignantly holding up a fat bill that contained a staff member’s telephone number.) It’s become so difficult to get other kinds of bills through a divided Congress that some are tacked onto bills that must be passed. Meanwhile, a bill such as the Affordable Care Act, which established a new national health care system, will of necessity be lengthy, but Republicans used that as an argument against it.

But the case of this year’s tax bill was different. Around 8:00 pm on Friday night, senators received a 479-page “amendment”—in effect, a new version of the bill that contained a hodgepodge of old and new provisions, the latter to buy the votes of remaining Republican holdouts. The normal procedure is that a couple of hours elapse between the offer of an amendment and its being voted on, in order to give a senator’s staff time to review it and explain it to the boss. But such heedfulness wasn’t to be allowed. Deals were made with individual senators that others knew little or nothing about. Jeff Flake, the rebellious Arizonian who isn’t running again, was given what he admits was an indefinite commitment that DACA immigrants would be protected. Susan Collins, the Maine moderate who had voted against the Obamacare repeal bill, got a mitigation of the repeal of the property tax deduction, allowing $10,000 in such taxes to be deducted. She also received some vague promises about lessening the effects of the proposed elimination of the tax deduction for state and local taxes, as well as of the individual mandate. She was told that there would be no cuts in Medicare, plus support for a bipartisan compromise plan to fix Obamacare. Another of those who had opposed the Obamacare repeal bill, Alaska’s Lisa Murkowski, had already been mollified by a provision that would open up the Alaska wildlife preserve to drilling for oil—a subject of a bitter, years-long fight.

The last Republican holdout, Ron Johnson of Wisconsin, obtained more favorable treatment for owners of businesses that report profits on tax returns for individuals (known as S companies, or “pass-throughs”). Most U.S. businesses, including most owned by the top 1 percent of income earners, are S companies. The break on “pass-through” income allows people who earn from S companies to avoid the current individual tax rate of 39.6 percent. (The Senate and House bills would drop these top rates slightly.) There’s no clear rationale for this, especially since S corporations already enjoy other tax benefits. Among those who will benefit from this provision are Johnson himself, whose estimated worth is over $30 million, making him one of the seven richest senators, as well as companies owned by the Trump family. Trump has been lying in saying that he doesn’t stand to benefit from the tax bill, even that he’ll be hurt by it. (Update: In fact, according to Democratic Senator Sherrod Brown of Ohio, Trump himself called in to a meeting of Democratic senators and administration officials and said that his accountant told him the the bill was killing him, adding, “We put in the estate tax repeal because there is nothing in this bill for rich guys like me.”)

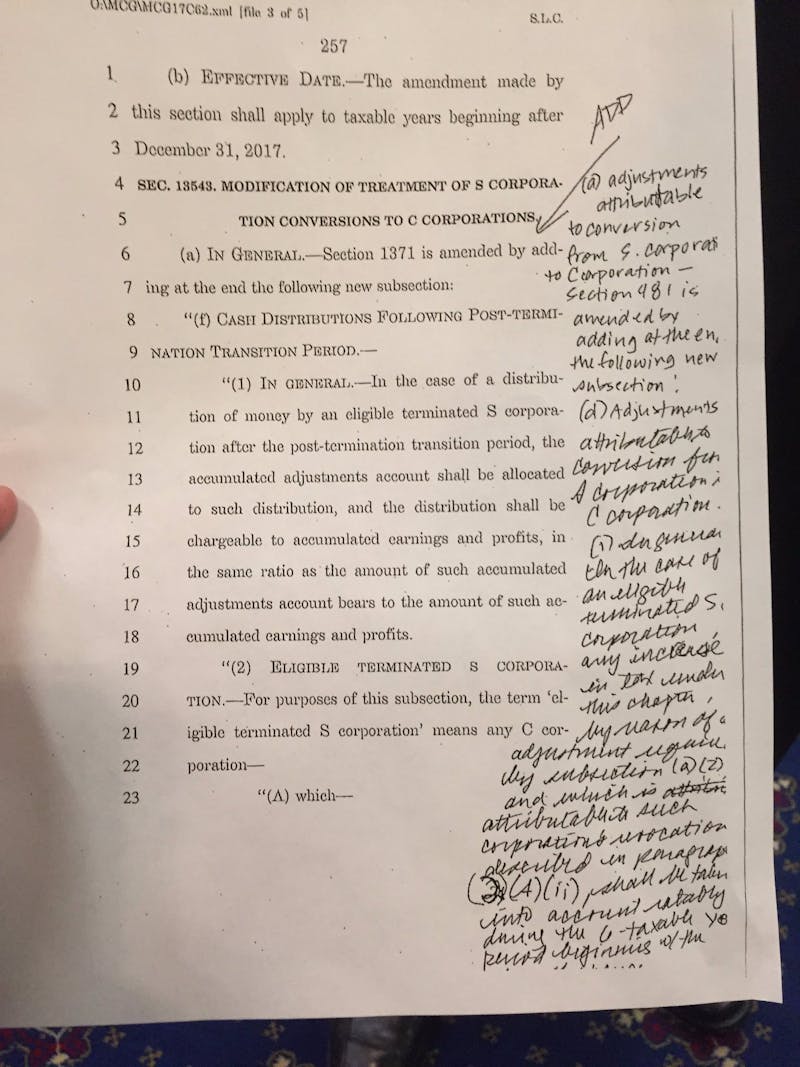

So frenzied was the last-minute drafting of this consequential bill that one provision was added in barely decipherable handwriting:

Tax bills are notoriously difficult if not impossible to read; the avoidance of plain English that would inform people of what the bill is doing is deliberate.

The collapse of the legislative process was complete. A bill affecting all parts of the economy was the subject of no hearings at all in either the House or the Senate. The same thing was true of the earlier Republican attempts to repeal and replace Obamacare. Both pieces of legislation, affecting millions and millions of people’s lives, were rushed through their respective chambers—but the tax bill was moved even faster so as to avoid giving people time to mobilize against it. The lapse of time before the Senate brought up Obamacare repeal allowed for such mobilization and the bill died in the Senate. That wasn’t to be allowed to recur in the case of the tax bill.

The traditional procedure, consonant with the Constitution’s intent, is that in the legislative process proposals are given a thorough airing, in which people with competing ideas are offered an opportunity to present them in hearings before the relevant congressional committee, and expert witnesses are also called to test the premises of the pending legislation. The public has an opportunity to hear these views, and the committee deliberates for the requisite amount of time and writes up the bill.

In 1973 reformers forced almost all the congressional committees to meet in the open, but over the years there’s been some backsliding. A side effect of the extended committee consideration is that there are less likely to be screw-ups in the drafting of the bills. Politicians got an opportunity to assess public opinion, and voters for an opportunity to register their opinion with their representative or senators, and to form coalitions on either side to fight for their position. A result is that if the bill passes, it’s likely to have more legitimacy.

None of these factors were present during the two major legislative fights so far this year. Republicans seem to have swallowed their own myth that the original Affordable Care Act was “rammed down our throats.” In fact, consideration of it lasted longer than a year and included lengthy hearings, committee mark-ups, and floor debate. Both the health care and tax bills were unpopular—about 25 percent of those polled supported the tax bill that came before the Senate, so the public was deprived of an opportunity to weigh in. In shutting out the public from consideration of the tax bill, the Republican leaders in both chambers aborted the democratic process.