One lesson we are meant to take away from 2017 is summed up in a widely memed phrase: Trust black women. It began with the 2016 election, when 94 percent of black women voted for Hillary Clinton, the highest percentage of any race-gender demographic. Had other groups followed their lead, we would have been spared a Donald Trump presidency and all that it has entailed in its whiplash-inducing first year. The Muslim ban, the threats to Obamacare, the repeal of net neutrality, the ban on transgender people serving in the military, governance via tweet, and nuclear brinkmanship with North Korea—all could have been avoided if the nation had trusted the wisdom of black women and voted accordingly.

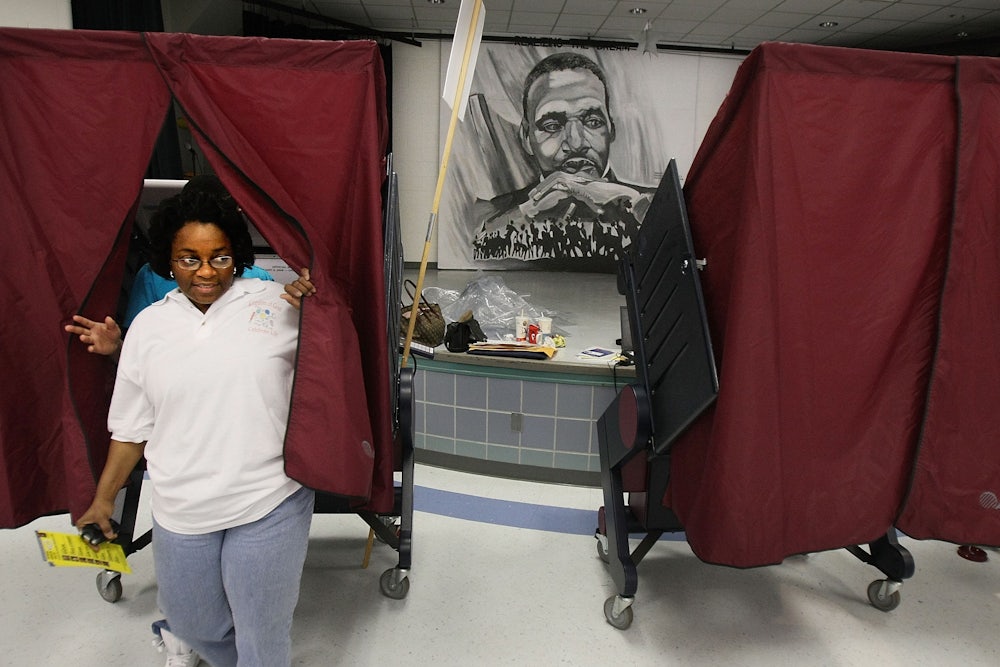

The potency of the adage was also on display when 98 percent of black women voted for Doug Jones, the Democratic candidate in Alabama’s recent special election to fill Jeff Sessions’s Senate seat, proving a deciding factor in ensuring a loss for Roy Moore, the former chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court who faced multiple allegations of sexual abuse of minors. Trust black women: They will save us from the worst of our collective impulses. The numbers bear this out, with 72 percent of white men and 63 percent of white women voting for Moore despite the allegations against him, not to mention a documented history of racist, sexist, and homophobic statements and policy positions.

“Trust black women” has made stars out of April Ryan, the longtime White House correspondent who has had terse back-and-forths with the president and his press secretaries, and Representative Maxine Waters, now affectionately referred to as “Auntie Maxine” for her relatable yet cutting critiques of the administration and consistent calls for impeachment. The fanfare would seem to suggest that, at last, black women are not only being taken seriously as a political force, but as a vital arbiter of morals and intellect.

However, when I step back from the rhetorical love fest, I think about Jemele Hill. The longtime ESPN contributor-turned-co-host of SportsCenter, the network’s flagship program, found herself embroiled in controversy in September after a tweet in which she said, “Donald Trump is a white supremacist who has largely surrounded himself w/ other white supremacists.” In some corners of the internet this would hardly register as a critique, rather a clear statement of fact. Trump’s entire public career supports the notion that he is deeply invested in the maintenance of white power, and his presidency has been no different. The remark, had it come from any other commentator with ostensibly liberal politics, would have been looked over as millions of tweets are daily.

But Hill works for ESPN. Her job, as she has been told over and over by people upset with her statement, is to analyze and comment on the world of sports. Never mind that the tweet came from her Twitter account, which is not an ESPN-owned property, or that it was Trump who injected himself into her world by offering his thoughts on the national anthem protests taking place in the NFL. Hill crossed a line—one that only exists if you happen to disagree with what she said.

The White House’s response, delivered via Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders, was that Hill’s comment was “one of the more outrageous comments that anyone could make” and that it should be a “fireable offense by ESPN.” The Trump administration’s attempt to pressure a private company over a person’s employment, simply because it didn’t like something she said, was one of the clearest examples of its authoritarian overreach. For its part, ESPN did not elect to fire Hill, but the company’s statement attempted to both distance itself from her and reflect a strict disciplinary stance.

ESPN did not invoke her right to free speech. It did not rebuke the administration’s attempt to fire a private citizen from the bully pulpit. It opted, instead, to cast her as a delinquent employee who had now received a stern warning.

A few weeks later, Hill was suspended from the network for two weeks, following tweets even more innocuous than the one that made her into a national headline. She’d been warned; now there was punishment.

In the year we were supposed to learn to “trust black women,” it also became clear that few actually want to do the labor required to make this trust active. There are plenty of problems with the phrase itself—the way it aggregates the identity of “black women” into a monolithic political voice, flattening the ideological differences among millions of black women and substituting a pragmatic sense of political calculation for vigorous debate. But more concretely, to “trust black women,” when there are no institutions that will stand strong behind a black woman when she is held to the fire, means that this “trust” is a hollow conceit. It’s a demand, once again, for black women to perform intellectual and emotional labor on our behalf, while asking nothing of ourselves when powerful forces are arraigned against them.

Hill was disciplined over a few tweets where she spoke plainly about the state of the country. ESPN felt no duty to her, even as it has made her one of the most prominent stars on its airwaves. There was a social media campaign in support of her, but it faded as the news cycle shifted. And while Jemele Hill is just one particularly vivid example, we can see other, less prominent black women being abandoned as soon as their votes have been tallied, most recently when incoming Virginia Governor Ralph Northam said he would not pursue an expansion of Medicaid, despite promising to expand health care access on the campaign trail. Northam received 91 percent of the vote of black women.

As a phrase, “trust black women” makes us feel like we are rectifying the historical hardship of black womanhood and finally honoring their contributions. But if “trust black women” really only means “rescue us, black women,” what we have learned isn’t all that different from what we have historically practiced. We lean on black women for their labor and counsel; we depend on them, in a practical sense, for our survival. But we also deny them the rights—free speech, equality, and the agency of a truly liberated existence—that we freely grant to others.