We must be grateful for almost any play that serves to bring Ina Claire’s playing to Broadway. And the dramatist in this case is also the director of the play; George Kelly’s talents in directing the company go very well with Miss Claire’s style.

“The Show-Off” seems to me about the best of our American comedies. But when George Kelly’s talent got itself into a kind of Ibsen perspective, the effect became confused. That certainty of comedy emphasis that he commanded so surely seemed to grow vague in outline and emphasis; the serious element lacked security in style and taste, and the higher sentiments ran close to the banal. His last effort up to now was “The Deep Mrs. Sykes,” which left people wondering why it was as good as it was without being really good at all when you came to think of it. This new play, “The Fatal Weakness,” is not unlike that of Mrs. Sykes. Very likely, in fact, it is not really as good. But it deals out its blasts on the ladies with the same witty venom, or flashing scalpel, or whatever we choose to call it. We have a romantic wife, a philandering husband, a married daughter as hard as nails, the wife’s sister, who joins her in trapping the male infidelities; and in the end, there is a divorce and the husband marries his mistress and the wife and sister go to the wedding.

Long before then, however, the wind has gone out of the play, and not even such playing, and such team work, as that of Miss Claire and Margaret Douglass can keep it interesting. Perhaps George Kelly’s kind of directing has something to do with the confusion or lack of general point. He is a remarkable man of the theatre when it comes to the details, the cues, the unbroken animation; but it is quite possible that for a whole scene, and doubly so for the whole play, his directing, for all its lively accuracy, its professional expertness, lacks emphasis. The mass emphases, as it were, that determine the play’s pattern and meaning are not firmly achieved. In the midst of frittering motivations and surfaces from daily life and character, the play’s whole scheme or content, in so far as it has any, is not established. The theatre world is too much with him, late and soon.

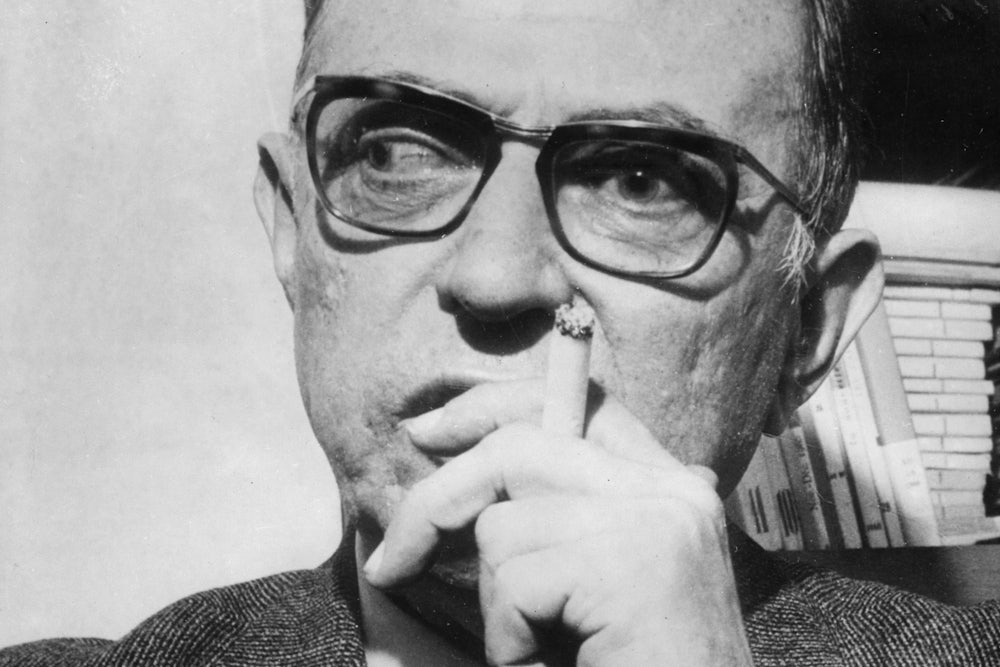

Jean-Paul Sartre’s “Huis Clos,” now produced at the Biltmore under the title of “No Exit” and in London as “Vicious Circle,” is one of those plays that only the script or a performance can convey to any extent. But it is a phenomenon of the modern theatre—played all over the Continent already—and may as well be envisaged as such. It should be seen whether you like it or not. The scene is a room in Hell where three people are doomed to torture one another forever. One is a journalist shot for collabo- rating with the Germans, one a Lesbian who has enticed a young woman away from her husband, one the wife of an old man and paramour of a young lover whose child she killed. There is no way to convey here the turnings and twistings of the situation, the remarkable subtlety of the tortures these people provide for one another, the high invention that goes into the design of their combined reactions and impacts. I may say only that John Huston directs the play with great intelligence, copes with all its infinite gradations, avoids all monotony, proves himself a fine theatre asset. Annabella, as the Lesbian, despite a heavy accent, plays better than I have before seen her play, and Claude Dauphin, also despite an accent, plays the collaborationist very well. Ruth Ford, convincingly beautiful and in a gown that might well be a landmark in the costume season, plays most intelligently and to the hilt the role of the infanticide, forever herself, forever glamorous and tortured. Paul Bowles’s version seems to be admirable.

The play is complete in itself, but we gain by knowing its connection with the philosophy of Existentialism, now so current in Europe. Too complex to convey here, it is concerned with the individual’s attitude of moral responsibility toward his acts and his thoughts. These people of the play are not in Hell only for their sins, but primarily for the basic lack in their characters.