At this unprecedented moment in American history, one question hovers over all the rest—it’s the question, previously thought to have been settled with the writing of the Constitution. The Founders were obsessed with not establishing a king in the new country. At the heart of the system of government they devised was the concept that the president must be accountable to the people. Article II, which establishes the presidency, includes a provision by which the Congress can remove a president from office “on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” Since then, Americans have believed that there’s a generally agreed upon process for holding a president accountable. The question that now hangs over us is this: What if in the current political context this remedy doesn’t work?

Donald Trump has forced us to wrestle with a problem that the Founders thought they had addressed: a president who flouts constitutional precepts and commits acts that exceed his stipulated and understood powers. Furthermore, in the case of Trump, he doesn’t accept the constitutional remedy for such a situation, and in fact has set out to undermine it. America has been an inventive, even an ingenious country, and so we tend to believe that there must be a solution to most every problem. We’ve overcome challenges—from natural disasters to a Civil War to a nuclear standoff with a strong hostile power that chose to put nuclear-tipped missiles 90 miles off our shore. Or have we been less inventive than lucky? And is our luck inexhaustible? To our knowledge, no special protection has been granted our tiny bit of the universe. For a long time we’ve been told that ours is a special nation. But what if it turns out that we’re not so special after all?

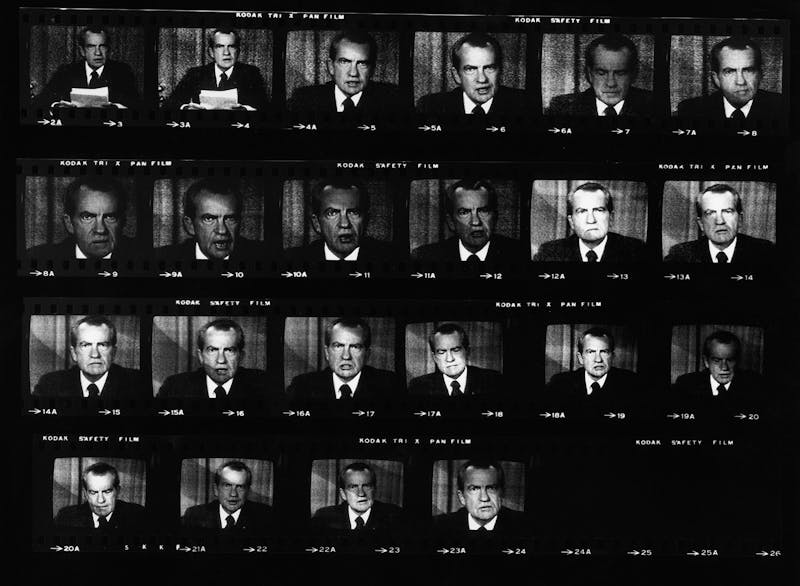

A critical lesson can be drawn from the fact that of the three impeachment efforts in this country’s history, only one was successful in satisfying the nation overall that justice was done—that of Richard M. Nixon. The other two—against Andrew Johnson ostensibly over his removal of a cabinet officer, and Bill Clinton ostensibly over his lying to the grand jury about his White House affair with Monica Lewinsky—failed because they were highly partisan exercises. Moreover, in neither case did the charges meet the constitutional standard for removal from office or reflect grave violations of the constitutional instruction that a president must “take care that the laws be faithfully executed”—the violations that underlay the Articles of Impeachment against Nixon.

The effort to impeach Nixon was widely accepted by the country because it proceeded on a bipartisan basis. Furthermore, Nixon had clearly presided over various infractions of the Constitution—illegal wiretapping, break-ins, a cover-up. Finally, the House Judiciary Committee’s proceedings in 1974 were conducted in a serious manner, with a high-level discussion of what the Founders intended, of what was appropriate to hold a president accountable for, so much so that many of us committed to memory passages from the Federalist Papers. The most pertinent and most cited quote was from James Madison’s Federalist 51:

If men were angels no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.

The chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, Peter Rodino, Democrat of New Jersey, and his top advisers decided at the outset that unless the impeachment effort had bipartisan support and came from the committee’s center (as opposed to the ideological left fringe that had first called for Nixon’s impeachment, well before the country was ready), the nation would be inflamed and the question of whether Nixon should be punished would remain unsettled. So as the Judiciary Committee went about its work, the most partisan Democrats and Republicans were isolated. A determined effort was made by Rodino and his allies to entice enough conservative Southern Democrats (these existed at the time) and moderate Republicans (these did, too) to work together in deciding whether Nixon had committed impeachable offenses.

These people were aware that they were setting precedents. Those of us who watched them in the Judiciary Committee’s unprepossessing hearing room, Room 2141 of the Rayburn House Office Building, knew that history was being made. The word “impeachment” is now tossed around freely, but as the first ouster of a president became an actual possibility, the idea of it was sobering and even frightening.

The leaders of the House Judiciary Committee proceeded with something else in mind, something they didn’t talk about out loud: that they needed to prepare not only for the full House vote on impeachment, but also, if the House did vote to impeach, for the Senate trial that would follow. This called for making as solid a case as possible for the conviction of Nixon and his removal from office, and that began with spending months gathering as much pertinent material as possible.

In the end the committee voted to charge Nixon with three Articles of Impeachment. The first charged him with obstruction of justice, through several acts. Article II not only charged Nixon with abuse of his presidential powers (for example, using federal agencies, such as the IRS, to wreak revenge on the president’s perceived “enemies”), but also, critically, held the president accountable for the acts of his aides. This wouldn’t apply to a one-off action by an aide, but “a pattern and practice” of some sort of untoward activity. The theory behind this is that the president sets the tone and cannot evade responsibility by winking and nodding and dropping hints. Aides come to understand what he wants done. To many close observers, this more expansive concept of a president’s accountability made Article II the most important one of the three that the committee adopted.

It would appear that, under this interpretation, should Donald Trump be subjected to an impeachment process—the likelihood of which I’ll get to later—his aides’ combined dealings with Russians close to the Kremlin might well validate a charge against Trump himself. Under this theory it won’t matter precisely what Trump himself did or didn’t explicitly say or do, or when he knew about it. Similarly, it was irrelevant whether Nixon knew ahead of time about the break-in at the Democratic National Committee’s office in the Watergate complex. He had said multiple times that he wanted to “get the goods” on DNC Chairman Lawrence O’Brien.

(This constitutional theory undermines the widely held view that Republican Senator Howard Baker in 1973 had presented witnesses with a penetrating question by asking, “What did the president know and when did he know it?” Baker, who was understood to be in touch with the Nixon White House, was helping Nixon by asking such a narrowing question. If, as they say, myths die hard, this one seems to have achieved immortality.)

When the first vote on whether to call for the impeachment of Nixon was taken shortly after 7:00 p.m. on Saturday, July 27, Room 2141 was dead quiet. The members cast their votes solemnly and with some emotion. It had been a draining process, conducted with dignity and with an awareness of what they were doing: voting to indict a president and perhaps begin his removal from the office to which he’d been reelected by a very large margin. The committee members understood that they couldn’t appear to take it lightly—nor, as far as one could tell, did they. The first vote was on Article I, which charged the president with attempting to cover up the crime of five “Plumbers” unlawfully breaking into the Democratic Party’s Watergate headquarters and with trying to obstruct an investigation into the matter. (Fortunately for the nation, the Plumbers—led by ex-CIA agents who were in the pay of the White House and the Committee to Reelect the President (or CREEP)—were stumblebums who bollixed just about every job they did. But what if they’d been skilled operators?) The first Article of Impeachment was approved by the committee by a vote of 27-11. Following the vote, Rodino went into the back room and cried.

The other two Articles—to impeach the president for abusing his powers and for contempt of Congress for withholding subpoenaed documents—were approved in the following days. As the managers of the impeachment process wanted, two proposed Articles were rejected in order to limit the charges to those that concerned the most serious matters and had won the greatest consensus. What were considered “political” matters—to impeach the president for the bombing of Cambodia and for his failure to pay the required federal taxes—were rejected.

Following the Judiciary Committee’s votes, it was widely believed that the House would go along and the only question was whether the required two-thirds of the Senate would agree. But then another scrap of tape—the tapes that had been recording incriminating conversations in Nixon’s office—was discovered that reinforced the fact that Nixon tried to obstruct justice. For the more timorous members of Congress, who were insisting on a “smoking gun” in a room full of smoke, this was it. (Nixon was recorded telling an aide to tell a CIA official to call the FBI and warn it that its Watergate investigation was jeopardizing national security.) Still, a number of Republicans in both chambers didn’t want to cast a vote to indict or convict Nixon, so, famously, a group of Senate and House Republican leaders went to the White House to tell the president that he was doomed and strongly implied that he should resign. It was a meeting, that, though it has been bathed in a heroic glow, was intended as much to get their fellow Republicans off the hook as it was to spare Nixon the ignominy of facing a trial in the Senate. It would be so much easier all around if Nixon would simply resign and go away.

This path out of his tragic presidency, an office he’d spent so much of his life trying to attain, had one major appeal for Nixon: He’d get to keep his pension. (He’d also receive substantial funds for staff to help him write his inevitable memoir to earn money and plot his road to redemption.) If, as the Republican leaders were telling him, the votes to impeach and convict him were in hand, he might as well take the money and go. No evidence has been produced that Gerald Ford made a deal to pardon Nixon, and, though this wasn’t the popular view at the time, I believed then and still do that Ford did the right thing. Dragging the matter out in a court trial would have guaranteed a long national distraction and more division. And it wasn’t as if Nixon was getting off light: No president had been brought this low.

That Nixon was forced to leave office led to many self-satisfied exclamations that “the system worked.” But it almost didn’t. Watergate was a much closer call than the movie-worthy triumphal ending suggested. The country was lucky in its leaders at the time, and that even includes Nixon. It was lucky in having Peter Rodino, a modest, fair-minded man, head the House Judiciary Committee, and it was lucky to have that particular assortment of committee members. It was lucky to have two independent counsels to investigate Watergate who were trusted by the public.

As for Nixon, though he hated the investigation—what president wouldn’t?—he didn’t go anywhere near as far as our current president has in trying to block or poison the inquiry into his role in the Russia affair. Yes, Nixon fired his independent counsel, whereas Trump, having learned nothing from history, fired FBI Director James Comey and tried to fire special counsel Robert Mueller last summer. Nixon was restrained in not burning the tapes that incriminated him (it was said at the time that this was because he’d been advised that that would have led to a charge of obstruction of justice, but Nixon also wanted those tapes for his own use when he would write his memoir). And at bottom Nixon, a lawyer, a former member of the House and the Senate, and a vice president for eight years, respected the system. Though he resisted turning over the tapes to the investigator, when ordered to by the Supreme Court, he obeyed. Nixon respected the institutions of government; Donald Trump doesn’t.

Most importantly, unlike the current all-out effort by a number of congressional Republicans to discredit Mueller and key figures in the Justice Department and the FBI, neither Nixon nor his aides and allies attempted to smear those investigating him. Murray Waas recently wrote for Foreign Policy that the three FBI officials whom Trump selected for special harassment had been confidants of James Comey, who had divulged to them in real time what he considered troubling efforts by Trump to cripple his investigation. This isn’t to say that Richard Nixon was a sweetheart of a man, or that using the instruments of government to punish his “enemies” was beneath him, or that he was above a bit of lying. (The White House spread rumors tying Rodino to the mob, but no unsavory connections were found.) But he recognized certain limits.

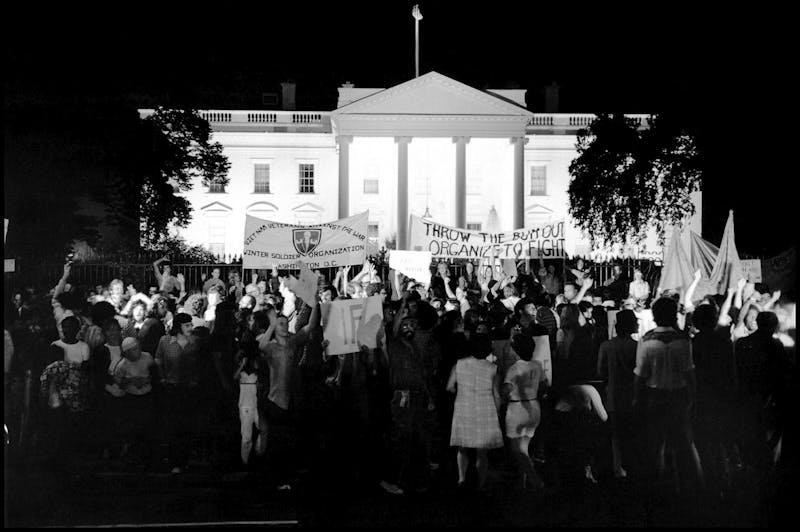

However, in getting his own independent prosecutor, Archibald Cox, fired, and in resisting subpoenas to turn over the tapes to prosecutors and investigators, Nixon turned Watergate into a constitutional crisis. Now Donald Trump has come close to precipitating another constitutional crisis by smearing and seeking the removal of FBI and perhaps Justice Department officials who could affect his fate; by encouraging his Capitol Hill allies to muck up the hearings on Russia’s interference in the 2016 election and any possible Trump campaign connections with that; by encouraging his collaborators to discredit Mueller and any information he may be getting; and by battling with his hand-picked FBI director, Christopher Wray. Trump, who unlike Nixon wasn’t schooled in government and has no regard for it, has proceeded like a blunderbuss against anyone and anything that he believes is in his way.

The greatest difference between Nixon’s time and now—and it could turn out to be crucial—is the nature of the Republican Party. This pertains not only to the specific question of impeachment, but also to the broader question of the state of our politics. Since the mid-1970s, when Nixon’s effective impeachment occurred, the Republican Party has moved considerably to the right. Its moderate wing that made bipartisan deals barely exists anymore. The critical move to impeach and remove Nixon could proceed from the center; now there is virtually no center.

The reasons the Republican Party moved to the right could make up a book (and in fact there are some about this subject). Redistricting as well as some social trends made moderate members more vulnerable to primary challenges. Money flooded into campaigns, particularly from such ideological groups on the right as the Koch brothers. Evangelicals became involved in politics in a way that they weren’t in 1974. And compromise is no longer widely accepted, especially by the far right, as a governing principle. The Republicans were challenged first by the Moral Majority, then the Tea Party, more recently the Freedom Caucus. None of these groups have had control over the party, but they made it increasingly difficult for its members to compromise. In fact, in recent years “compromise” has become a dirty word.

There’s a journalistic tic to be “even-handed” about polarization in this country, to engage in “both-sidesism.” But the plain fact is that the Democrats haven’t self-radicalized to the extent that the Republicans have; the Democratic struggle between left and center has leaned more toward the left, but it’s essentially still unresolved. There’s no clearer example of the profound change in the Republicans’ behavior than when their presidents faced an existential crisis then and now. In 1974, the Republicans didn’t engage in hijinks designed to wreck any congressional inquiry into Watergate. Scenes that were unremarkable in 1974 of House Judiciary Committee Democrats and Republicans working together to fashion an Article of Impeachment are inconceivable now. The most rightward Republicans on the House Judiciary Committee then—the two or three who continued to maintain Nixon’s innocence—were rendered irrelevant, while their descendants are throwing bombs. Moderate Republicans took some time to come around then; they had to appear to be reluctant no matter what they thought, but they did so. And there were enough of them to make the difference.

A starkly different approach to impeachment was the highly partisan attempt in 1998 led by then-House Speaker Newt Gingrich to impeach Bill Clinton. The ostensible ground was that Clinton, under oath, had lied to a grand jury about his affair with White House intern Monica Lewinski. Perish the thought, insisted Gingrich and his Republican colleagues, that this was about sex—but it was about sex, dressed up as an offense against the Constitution. Clinton was guilty as all get-out of sexual recklessness: He even made himself a security risk, subject to blackmail. But this wasn’t enough to remove him from office. The majority of the country wasn’t on board with this radical act, and even punished the Republicans in the 1998 election by costing them five seats in the House. The Republican caucus, many of whom were already disturbed by Gingrich’s practices, forced him to surrender his leadership position, and so he left the House.

In the end, Clinton was impeached by the House but the Senate fell short of the two-thirds vote to remove him from office. The process that, 25 years earlier, had fulfilled Madison’s vision of a government that could control itself, had become a partisan weapon. The impeachment of Bill Clinton was a long, distracting ordeal, and its partisan basis offers an example of why it should be extremely difficult to remove a duly elected president from office. I spoke not long ago with former Vice President Walter Mondale, a Minnesota liberal as upset as anyone about the Trump presidency, who said to me, “There should be a heavy burden on whoever wants to delegitimize an election.” He was opposed, he said, to the concept of making impeachment easier. “I’ve told people not to go there,” Mondale said. “It could be very destructive.”

Many of those who are frustrated by the difficulty of removing Trump from the presidency via impeachment have turned to the Twenty-Fifth Amendment to the Constitution as a possible vehicle for achieving their goal. It was passed by Congress and ratified by the states in 1965, following the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963, which left the new president, Lyndon Johnson, whose health we learned later was precarious, without a vice president until the next election. The amendment deals with one contingency the Founders had overlooked: What to do in the case of a physically incapacitated president. Though it wasn’t designed for the current situation of a president whose mental capacities are being questioned by his critics—though some Republicans on Capitol Hill, particularly in the Senate, have also privately discussed the issue—numerous people have looked to it for an alternative way to oust Trump, on the grounds that he’s not mentally or temperamentally capable of holding the office of president.

They cite the mounting evidence of Trump’s inattention to what’s happening around him, his poor memory and decreased vocabulary, as signs that he isn’t mentally equipped to do the job. Yes, Trump volunteered for a cognitive test in his recent physical examination, and was said to have done well on it, but it was one with a very low bar. Besides that, it’s gradually becoming understood that the Twenty-Fifth Amendment requires an objective standard, an unquestioned debilitating illness such as the stroke that disabled Woodrow Wilson. Earlier this year, Jay Berman, a Washington attorney who was an aide to Democratic Senator Birch Bayh when the Senate Judiciary Committee drafted the Twenty-Fifth Amendment, said in a television interview that it wouldn’t apply to perceived mental limitations or a president’s capability of governing, and therefore it wouldn’t apply to Trump’s real or perceived condition. Berman said, “There’s a difference between unable and unfit.” He added, “Donald Trump was duly elected to do the things he’s doing now.”

Oddly, the amendment relies on the vice president to begin the procedure—practically speaking the last person who should initiate a process to remove the president from office. The amendment also provided an alternative of a special committee established by the Congress to decide the president’s ability to function, but it’s hard to see how such a move could be free from the taint of a putsch. Like impeachment, the Twenty-Fifth Amendment should be extremely difficult to implement, unless we want to be like unstable countries that change leaders according to the national mood. Berman is correct that Trump was elected to do essentially what he’s doing. Questions about his mental health were also aired: people wrote during the presidential campaign that he suffered from a narcissistic personality disorder, far more serious than the self-regard of your average politician.

Richard Nixon presented us with a real constitutional crisis—the question of whether a president can be held accountable by the other branches of government. Watergate was much more serious than the cops-and-robbers version of the movies. In various ways Nixon defied presidential accountability and abused the power of his office. He violated the constitutional requirement that he “take care that the laws be faithfully executed.” On the basis of what I learned from sitting through the House Judiciary Committee’s discussions of what constitutes an impeachable offense, I believe that Donald Trump has committed a number of impeachable offenses.

It’s important to keep in mind that an impeachable offense isn’t necessarily a crime, though a crime can also be an impeachable offense. Furthermore, the precedent is that a one-off event (short of murder or something about as heinous) isn’t necessarily an impeachable offense; remember that the House Judiciary Committee looked for a “pattern or practice” of some sort of unconstitutional behavior.

For example, the evidence that Trump has obstructed justice in both senses—criminal and impeachable—is quite strong. To prove it’s a crime one must also prove intent; it would seem fairly evident that Trump’s serial attempts to stop or interfere with the investigation into Russia’s role in the 2016 election, and into whether there was collusion or a conspiracy between Russia and the Trump campaign, demonstrate an intent. He’s apparently attempted to obstruct justice through a series of actions, including the firing of James Comey. He has abused power by pressing the Justice Department to take action against his previous election opponent and against law enforcement personnel he reportedly wants fired, including FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe, who stepped down under pressure this week, and Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein. With Rosenstein out of the way Trump could find a more complaisant soul who’d be willing to fire Robert Mueller.

Moreover, under the House Judiciary Committee’s broadened definition of an impeachable offense that holds a president accountable for the actions of his subordinates, even if his hand isn’t found in any single act, Trump could possibly be held accountable for the multitudinous contacts between his aides and allies and Russians close to the Kremlin. Much of this depends, of course, on what special counsel Robert Mueller finds.

Further, though every president lies at some point, the sheer volume of Trump’s lies—according to The Washington Post he committed roughly 2,000 false or misleading statements in his first year—put him beyond accountability to the citizens; at some point a difference of degree becomes a substantive difference. A convincing argument can also be made that, through his failure to separate himself completely from his family’s businesses, Trump could be impeached for accepting foreign emoluments, specifically barred by the Constitution, and for violating ethics laws. Some would add other offenses to this list, others wouldn’t go as far.

But if there are grounds for removing Trump from office, at this time this country isn’t near enough to a consensus for it to happen. On the right, while there are signs that Trump’s famous base is eroding, it’s still strong enough to protect him from removal from office. On the left, Democrats are actually split because many liberals have adopted the view that it’s too horrifying to contemplate Mike Pence succeeding Trump, a bizarre view since Pence’s more troglodyte social views aren’t going to have enough support in the Congress to prevail, and, to get to the heart of the matter, Pence isn’t crazy. It’s not that such a consensus formed as the House Judiciary Committee proceeded on the matter of impeaching Richard Nixon, but that Nixon and his party didn’t resort to all kinds of tactics to fight such a proceeding. In other words, there developed a bipartisan consensus that the impeachment process itself was legitimate.

It’s possible that the critical lack of consensus now could change with some extremely damning discovery, or with Mueller’s report. If, as many assume, the Democrats sweep the House this coming November, they could be in a position to impeach Trump—if the party leadership so desires (a matter they don’t want to talk about now). But barring highly damning news or events, there’s unlikely to be the required sixty-seven votes in the Senate to convict Trump and thus remove him from office.

It turns out that, under the political conditions we currently find ourselves in, the American system of government does not have the means to remove an unfit president from office. The hard truth is that, if there’s no congressional remedy for having elected someone unfit to serve, the process for protecting the country from such a person inhabiting the Oval Office has to begin somewhere else. In the short term, we have to educate the populace, starting with ourselves, to not indulge in the kinds of attitudes that allowed a person like Trump to win in the first place: that elections don’t matter, or that the major party candidates aren’t ideologically pure enough or sufficiently likeable to cast a vote for. (My own view is that the parties’ nominating systems need an overhaul, but that’s another matter.) In the future, we have to create the political conditions by which the government can govern itself. Meanwhile, all we can do is to try to survive Donald Trump’s presidency.