Recently, a book by Patrick J. Deneen, Why Liberalism Failed, caused a commotion in American political-intellectual circles. A total of three New York Times columnists—the opinion writers David Brooks and Ross Douthat and the new book critic, Jennifer Szalai—responded to it with different takes. But they all shared with Deneen an underlying assumption: that, as Szalai put it, liberalism—the defining political doctrine of individual rights and freedoms—was “the founding creed of the United States.”

Liberalism was not the founding creed of the United States. The Founders were adherents of classical republicanism—also known as civic republicanism or civic humanism, an older democratic doctrine conceived around the common political good and the welfare of society as a whole—before modern liberalism. Thomas Jefferson composed the Declaration of Independence, which fact has encouraged the belief that America’s founding was fundamentally liberal. But he named his political party the Republicans. He and the party’s co-founder, James Madison, were two of the most stalwart republicans of the age.

The idea that the United States is and has always been quintessentially liberal was solidified by Louis Hartz, whose book The Liberal Tradition in America held sway in American political thought from the mid-1950s into the mid-’70s. Hartz argued that because America never had a feudal class system to overthrow, it lacked Europe’s reactionary conservative tradition, as well as its radical socialist one, and had only liberalism as a philosophical guide—a thesis that was accepted as gospel in the academy.

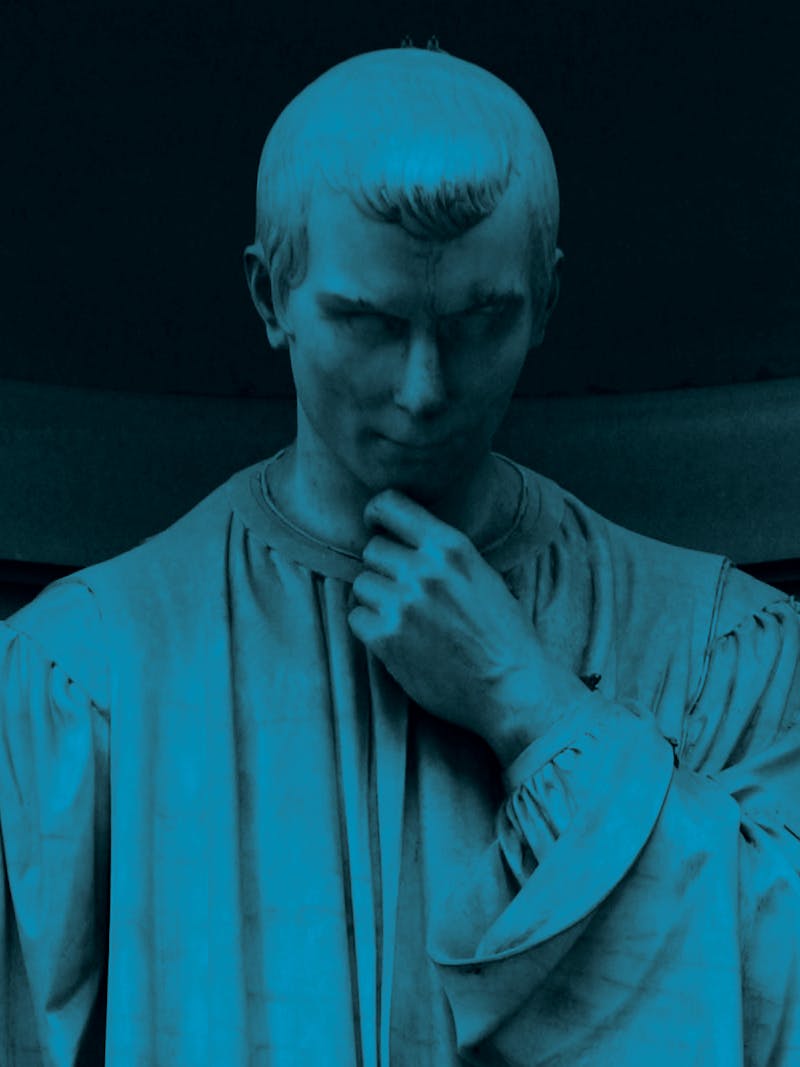

In 1975, however, J.G.A. Pocock published a tome called The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition, bringing the civic republican tradition to the fore. Dating to early Renaissance Florence, its most influential exponent was Niccolò Machiavelli, whom Brooks, channeling Deneen, accuses of leading modern political thinkers to “reject the classical and religious idea that people are political and relational creatures” and to decide that “you couldn’t base a system of government on something as unreliable as virtue.”

But the essence of Machiavelli’s political thought is the opposite: He advocated republican government, which depends on citizens motivated precisely by virtue to look beyond their private, self-centered interests. In fact, the premises underlying the republican credo come ultimately from the ancient Aristotelean conception of the human being as a “political animal,” whose highest interest was realized in participatory self-rule.

Pocock’s revolutionary opus created a whole new direction for creative discourse in the discipline of political philosophy. Two of the most important works in the new field came from a pair of younger scholars, Robert D. Putnam and Michael J. Sandel, not long after the collapse of the Soviet Empire. Although the march of liberal democracy seemed irreversible at the time, Putnam and Sandel separately had perceived a growing disenchantment with its day-to-day workings in America.

Both set out to find antidotes for this malaise, and both—pursuing different lines of research and analysis—came to the same conclusion: Liberalism, as doctrine and practice, does not provide adequate support for a democratic order. To endure, democracy needs buttressing from a strong republican ethic.

Putnam studied the Italian political system after it was radically decentralized, beginning in 1970, with the purpose of determining which areas of the country adapted best to the practice of local democracy. He found the regions that did were essentially those that had comprised self-governing communal republics during the Middle Ages and that were characterized by what he calls a “civic community.”

In Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy, Putnam identified the key characteristics of a civic community: high levels of civic engagement, political equality, solidarity, trust, and tolerance, along with the kind of rich associational life Tocqueville described in his commentaries on American democracy. “Such a community,” Putnam says, “is bound together by horizontal relations of reciprocity and cooperation,” rather than “relations of authority and dependency.”

Sandel, in Democracy’s Discontent: America in Search of a Public Philosophy, traced the gradual decline of the civic republican ethic in America from its high point just before and during the American Revolution, through its post-Revolutionary heyday in the first half of the nineteenth century—when it was allied with the now quaint concept of “free labor”—and its last great stand during the Progressive Era, to its final defeat during the latter stage of the New Deal, when it was submerged by what Sandel calls “procedural liberalism,” a philosophy that emphasizes, per John Rawls, the “right” over the “good.”

Douthat asked in his column what new political philosophy can now replace liberalism, if liberalism has failed and is on the way out, as Deneen alleges. But the apolitical response Deneen offers, mercilessly dissected by Szalai—repairing to the land with your family to grow your own food and practice your religion—gives the game away. There is nothing on the horizon to replace liberalism. Nor need there be. The United States already has a philosophical tradition, hidden in the broad daylight of our civic history, that has composed with our liberal values before and can revive our politics again.