Graham passed away at his Montreat, North Carolina, home on Wednesday morning. Arguably the most important evangelist in American history, he applied a Southern preacher’s earnest demeanor to the eternal Christian project of winning souls. As NPR reported on Wednesday:

His influence as a moral and spiritual leader in 20th century America was such that one historian said Billy Graham could confer “acceptability on wars, shame on racial prejudice, desirability on decency, dishonor on indecency, and prestige on civic events.”

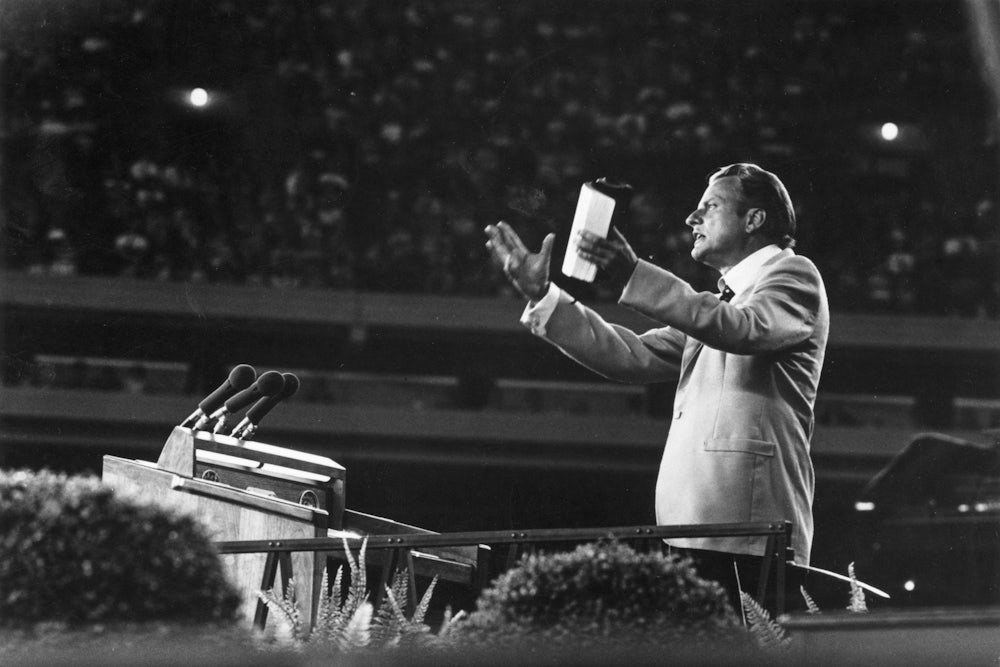

His Crusades, which began as modest tent revival services, earned him both a loyal following and disdain from some of his peers in the faith. The latter was because Graham was no theologian, and held only a bachelor’s degree in anthropology from Wheaton College in Illinois. He further irked fundamentalists by promoting a more open engagement with the secular world—though they differed little on actual doctrine. Graham believed the Bible was God-breathed, or infallible in every respect, and thus should be interpreted in a literal fashion.

Aside from the Crusades, Graham became best known for his influence on American politics. This did not always go well for him. Despite a record of condemning some forms of racial prejudice, he also appeared on the Nixon Tapes complaining about the Jewish “stranglehold” on the country. He apologized for those remarks in 2002, but they seriously damaged his credibility at the time. And Graham’s work—becoming a counselor to presidents, bringing religion into politics—may have unleashed consequences he did not intend. What “evangelical” means now is not what it meant when Graham began his career. It’s mutated from religious identity to demographic signifier: It increasingly means “white” and “Republican.”

Though Graham reached out to both parties, his emphasis on political engagement helped set the stage for the marriage of evangelicalism to the Republican Party. It is perhaps the greatest irony in Graham’s superlative life that his son, Franklin, is a vituperative, Muslim-hating, gay-bashing reminder that the admixture of Christianity and Republican politics benefited the latter more than the former.