When the survivors of the Valentine’s Day mass shooting at Parkland, Florida’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School took to Florida’s capitol in February, sparking nationwide actions in solidarity, they were echoing the actions of an earlier group of young people protesting a shooting.

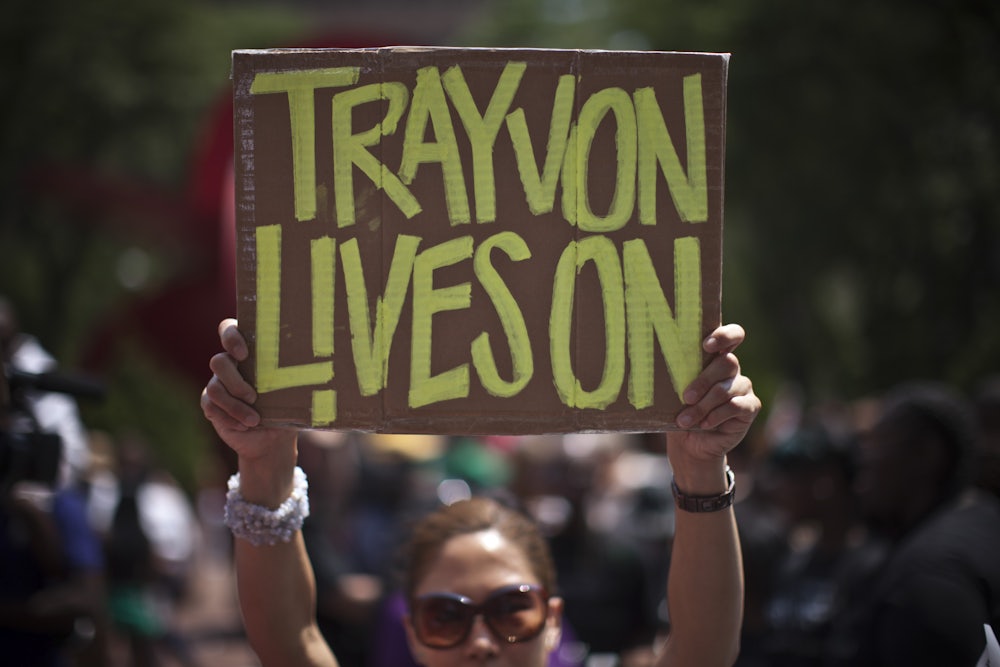

George Zimmerman’s July 13, 2013, acquittal for the killing of Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida, brought the Dream Defenders, an organization formed after Martin’s death, to the capitol to demand that legislators take action, particularly against the state’s “Stand Your Ground” gun law. Governor Rick Scott turned up wearing cowboy boots with Confederate flags printed on them. He told them there was nothing he could do.

The Parkland students descended on the capitol just days from the six-year anniversary of Martin’s death, an anniversary that also commemorated the creation of many of the groups that have made headlines in the years since. Black Lives Matter, Dream Defenders, Million Hoodies Movement for Justice, BYP 100, and others were formed in the aftermath of Martin’s death, yet are mostly separated in the press and the political debates from the issue of “gun violence.” Their demands are a reminder that the problem of gun-related deaths is rooted not just in a surfeit of deadly weapons, but also in a culture of racialized violence and inequality.

Even if the students in Florida do not think of their

movements as the same, they are doubtless learning from the years of movement

activity that they have lived through. Just in high schools in recent years, we

have seen walkouts over Trump’s election;

over deportations;

in support of striking teachers’

unions and to save public

schools slated for closure

or budget cuts; in support of Occupy Wall Street; against police

violence; and, yes, calling for justice for

Trayvon. This is the world in which the Parkland students

were shaped, and it should be no surprise that they have a toolbox of

tactics, including social media, that they are using to bring attention to

their cause. “Adults like us when we have strong test scores, but they hate us when we have strong opinions.” wrote Parkland survivor and organizer Emma Gonzalez.

It shouldn’t surprise us either that they appear to be getting results. Recent years have brought us a burgeoning awareness of American inequality, of the failures of quick fixes, and of the increasing dysfunction of our political institutions. Mass shootings feel like a particularly brutal symptom of America’s brokenness, one that manages to penetrate even into the lives of the comfortable. They react to mass shootings—the really bad ones, anyway—the way they don’t react to the fact that Flint still doesn’t have clean water.

“Every tragedy is worth fighting for and organizing around, regardless if it is a mass shooting or everyday violence that happens in a certain community,” says Dante Barry of Million Hoodies. “While people continue to organize in Florida, the most impacted communities have been leading these fights for a very long time and we need to think about how we can be in solidarity with those movements.”

Million Hoodies began with an online call to action. From there it became a march and an online petition that, Barry notes, got global support. “From then on, there has always been general global support for black-led movements, but there hasn’t been a lot of capital raised for black-led movements,” he says. “We are literally fighting for crumbs just to do any bit of work on things that have been devastating our communities for a very, very long time.”

By now many people have rightly noted the difference between the reactions to the Parkland students and to the movement for black lives. Though the NRA and hardline conservatives react badly to both—accusing them of being crisis actors in the case of the Parkland students, and of being violent enemies in the case of black-led movements—the Valentine’s Day shooting survivors have been welcomed with open arms (and open wallets) in the center and much of the left. It’s not that the students of Parkland are all white and well-off—they aren’t, not even the most-photographed, like Gonzalez. But the kernel of truth in the conspiracy theories about shadowy funders supporting the Parkland students is that there is some big money behind gun control, wealthy backers like billionaire former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

There are lots of local movements aimed at reducing gun violence but they mostly operate outside the context of what we think of as gun control. They are focused instead on slowing violence in their communities, and they do the grassroots work that the big funders are averse to.

On the national level, meanwhile, there is a disconnect between policy advocacy and the needs of people on the ground. Some proposals being put forward would criminalize black and brown people or increase inequality, producing safety for some at the expense of others. Barry points to the last big showdown in Congress over gun control, which saw progressive stalwarts sitting in to demand a vote on legislation that would bar people on the “no-fly” terrorism watchlist from buying guns. Yet that “no-fly” list is a deeply flawed document that has long been criticized as a form of racial profiling. Background checks, too, rely on a criminal justice system that is lenient on the white and wealthy and harsher on everyone else.

Gun control is mostly discussed as though there are commonsense solutions that politicians, aswim in NRA cash like Scrooge McDuck, simply refuse to enact. Yet “gun control” in Mayor Bloomberg’s New York meant stopping and frisking young men who look like Trayvon Martin. Stop-and-frisk rarely found weapons, but it did subject hundreds of thousands of young people to humiliation and violence. Furthermore, the NRA has power not simply because it has money, but because it has a base, which is mostly white and practices the grievance politics that helped Trump get elected.

The organizations formed after Trayvon Martin’s death do not advocate for quick-fix solutions. They are part of a movement to end inequality, a movement that understands that stricter gun laws will not end the violence of racism and poverty in America. This is what their critics really mean when they say, “They have no demands.” They have demands, it is just that those demands are huge and systemic and will require change from us all. Those demands cannot be met in the space of a legislative session, though certainly legislators can do more than voting to put guns in the hands of teachers.

“We live in this society that is highly unstable, there’s so much insecurity,” says Ciara Taylor, one of those who occupied the Florida capitol in 2013 to protest George Zimmerman’s acquittal. “Parents aren’t sure if they’re going to have enough food on the table, children are feeling insecurity in schools that are like prisons, with metal detectors, armed security that didn’t even protect the children. You fear being detained and incarcerated in your own classroom, fear walking down the block in your own neighborhood—Trayvon was killed in his own community.”

So far, the Parkland students have at least resisted demands that would make schools more prisonlike. They have shrugged off demands for more metal detectors and guns for teachers even as the Florida legislature voted to fund and arm “school marshals.” Teachers responded with the hashtag #ArmMeWith, listing the things that they need on the job more than a gun: more counselors, more teachers, more teaching rather than testing, and most of all more funding. The Florida legislature instead tried to break the teacher’s union just days after its members died protecting students. There is money, apparently, to arm teachers but not to pay them a decent wage.

More armed guards in schools is an idea likely to result in safety for some at the expense of others, especially students of color. The presence of police in schools makes students more likely to get arrested for things that would have been considered discipline issues. And teachers could also be put at risk with more guns in schools. As the mother of Philando Castile, the Minnesota school worker shot by a police officer after he mentioned having a legal gun, noted: “If you have three words—black, man, gun—there are no negotiations. They could be killed when all they wanted to do was protect their students.”

To really lessen the violence that Americans, students and otherwise, face will require broad changes and an attention to existing inequalities and injustices. “I’ve come to understand the larger problem to be our culture of violence, of exploitation, of dominance, of hatred and fear of the Other and I think that a lot of that boils down to this system of racialized capitalism,” Taylor says. “Until we address how that system has pervaded our community and marginalized segments of our communities we’re never going to be able to get violence out of our communities in a real way.”

There are signs that the Parkland students understand this. Gonzalez called for increased mental health care in an op-ed, and other students have retweeted calls for attention to Flint and to Puerto Rico, making connections with the Dream Defenders and other grassroots groups. But the sudden national attention on one group of activists can lead to resources being diverted away from grassroots work that has made important strides. “People should be putting in resources, time, and really listening to particularly black-led organizations that are not just focused around gun violence or violence prevention, but also look at policing, economic development, health care, housing, and all of the other things that actually widen the level of inequality for our communities,” Barry says.

On Monday night, the New York City chapter of Million Hoodies took the streets again to remember Trayvon Martin and to highlight the connections between police violence, criminalization, and gun violence. They launched a campaign on February 5 called “Life at 23,” sharing what their life was like at the age Martin would be now, or, if they’re younger, their expectations for what it will be like. It did not get the press attention that the Parkland students have gotten, but it is a campaign they would likely understand—they too had cause to wonder if they’d make it to 23.

“We have to have these overlapping conversations around gun violence, whether it’s in mass violence like this, peer to peer in our communities, or gun violence happening as a result of the criminalization of young people, poor people, people of color,” Taylor says. To the young activists working now, she advises, “Continue to ask the question: Why? Why are things the way that they are? Why do we have a system that values profits over people so much that our country is willing to continue unrestricted access to guns?”