It’s always tough to be a public school teacher, but it is especially tough in Oklahoma—and Oklahoma teachers are ready to walk in protest.

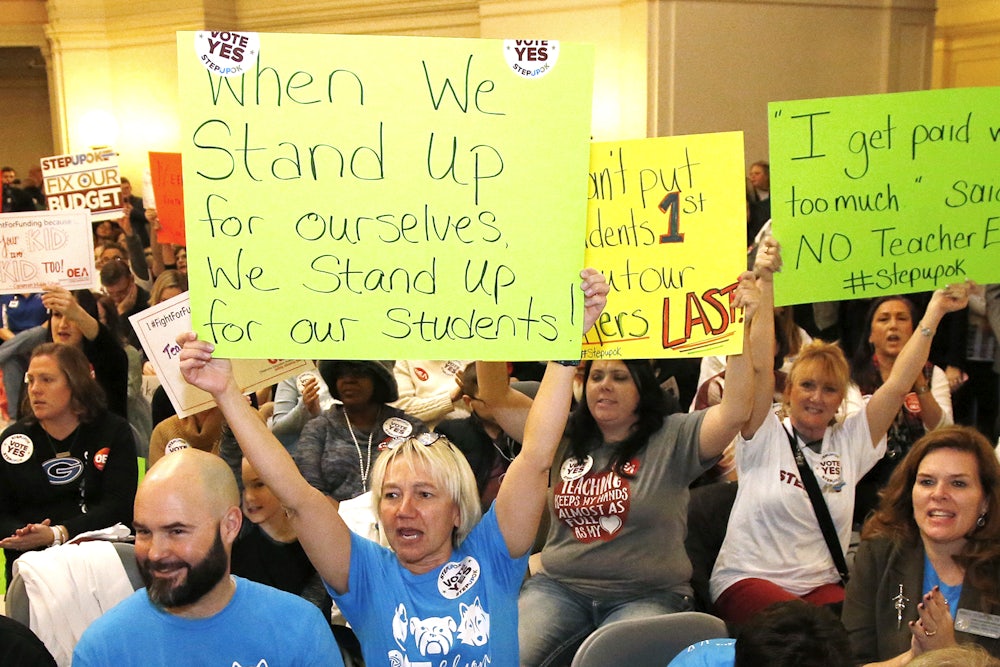

Inspired by West Virginia’s recent strike and by their own longstanding grievances, they’ve begun using social media to organize support for a statewide walkout. On Thursday afternoon, the Oklahoma Education Association will hold a press conference with public workers to announce demands: If the state legislature doesn’t pass a pay raise and increase funding for public schools by April 1, teachers will strike on April 2. As in West Virginia, Oklahoma teachers technically do not have the right to strike; their walkout will be a work stoppage.

“Educators have not had a raise since 2008, neither have education support professionals, neither have state employees,” explained Katherine Bishop, the vice president of the Oklahoma Education Association. “State education funding has been cut more than any other state in the nation. Quite frankly, school budgets have been cut so much that teachers do not have access to the materials they need to do their jobs.”

In the Facebook groups where teachers and parents are coordinating the walkout, “West Virginia” has been a common refrain. Earlier this week, following a nine-day strike that shuttered schools across the state, teachers won a 5 percent pay bump. If they did it, the reasoning goes, so can we. Some West Virginian teachers have even joined the Oklahoma Facebook groups. There are plenty of reasons for the cross-state solidarity: Oklahoma and West Virginia teachers suffer similar structural indignities.

In some cases, Oklahoma’s public schools face unusually dire straits. Average salary for an Oklahoma public school teacher is the lowest in the country, and the state faces a severe teacher shortage. Ninety-one public school districts out of 584 have reduced the school week to four days, according to Bishop, and at some schools, teachers can only make 30 photocopies a week to provide materials to all their students. The situation is so serious that, in 2017, the Oklahoma City school system threatened to sue the state legislature for underfunding its schools. And the crisis predates 2017: Oklahoma teachers also walked out in 1990 over low pay.

Public school dysfunction is directly created by statehouse policies. Legislators have cut funding for public education while cutting taxes, leaving public school teachers and students with crumbs. As Rachel Cohen recently noted for The Intercept, Oklahoma cut per-pupil spending by 28.2 percent from 2008-2018, the steepest drop in the nation. In practical terms, that’s a loss of $1,000 per student over one decade. Not surprisingly, the state bleeds teachers—neighboring Texas is a popular destination—and legislators have shown little interest in keeping them around. To the contrary, the state has invested in private education at the direct expense of public schools.

Oklahoma, unlike West Virginia, created two “school choice” programs: The Lindsey Nicole Henry Scholarship for Students with Disabilities, and the Oklahoma Equal Opportunity Scholarships Program. Based on data published on the website of EdChoice, an organization that supports school vouchers, the state will spend millions on the Lindsey Nicole Henry program during the 2017-2018 school year. The equal opportunity scholarships, meanwhile, are funded by tax credits: “The allowable tax credit is 50 percent of the amount of contributions made during a taxable year, up to $1,000 for single individuals, $2,000 for married couples, and $100,000 for corporations, now including S-Corporations,” explains EdChoice.

Oklahoma caps the equal opportunity scholarships program at $5 million, with $3.5 million allotted specifically to private school scholarships. Between its two school choice programs, the state voluntarily surrenders millions of dollars, in direct funds and in lost tax revenue, to private schools every year. Many of these private schools are also religious in character, meaning they can discriminate against LGBT students, and they’re subject to almost no oversight.

Bishop says the state’s charter schools, though technically public, are also part of the problem. “The school choice movement has had an effect on our overall public school funding by taking funding away from our public schools,” she explained, and added, “We have virtual charter schools that students can go to, and they enroll in those virtual schools, and the schools keep them until the October 1 headcount.” The reason is so the charter schools can secure the funding they need, but afterward those students can be kicked out for any number of reasons, including low grades and disability status. “And then we see them back in our schools,” Bishop said.

Meanwhile, teachers say they’re so underpaid and overworked that their situations have become untenable. “I’m an assistant band director; this is my fourth year doing it,” said Beth Wallis. “I wear a lot of hats because it’s a smaller district. Up until this year, I taught all the way from Pre-K through 12th grade. This year they rearranged the schedule a little bit, and so now I teach 4th grade music and then 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, and high school band, plus jazz band and a kindergarten class.”

“I could move to Texas right now and get an $18,000 raise,” said Alberto Morejon, who teaches 8th grade U.S. history at a public school. Morejon also organized one of the primary Facebook groups where teachers have been planning the walkout. “A guy actually posted a question on the page that asked teachers what they did for extra money. It got over 3,000 comments. People said that they drive Uber on the weekends, or that they deliver newspapers. I know a ton of teachers who who get part-time jobs in the summer because they need the extra money.”

Some teachers have left traditional public education altogether. Daryl Gandy, who teaches at Epic Charter Schools, told me he left his job with the Oklahoma City schools over low pay. “A traditional teacher who’s been in the system for about five years or so in the Oklahoma City public schools made about $32,000 a year,” he explained. “And the average teacher at Epic makes, I believe, around $61,000 a year, though that can change depending on various circumstances.”

“I knew a few teachers who bartended. Some mowed lawns on the weekend. Others worked in retail. Pretty much any side gig that you could think of, teachers were doing it. It was pretty crazy,” he added.

Though their grievances are old, and talk of a walkout has been circulating for months, teachers credit West Virginia’s recent strike for spurring new momentum. “The page I made has about 60,000 people now,” said Morejon. “I think the combination of that page and the West Virginia strike is what really got people going. Every teacher I ask is on board.”

“Without West Virginia, I don’t think that the momentum would be here at all. So it has made our argument a lot stronger,” Wallis echoed. She added that she’s hopeful people will take teacher concerns more seriously now: “The best way to get people to listen is to get them to realize what their kids go through everyday. And now we’ve brought that to their attention a little bit more, and made them realize that at the end of the day it’s not about teachers getting paid more. It’s about the fact that all the teachers have left the state because they can’t feed their families.”

“What it really boils down to,” said Morejon, “is that legislators think they can just step on teachers because we’ll keep showing up to work. I think right now we’ve got a movement started. We’re tired of being stepped on and tired of being treated the way we are.”

Now the walkout looms. The organizing process has been rocky at times: the Oklahoma Education Association’s original strategy, which would have given the legislature until April 23 to act, wasn’t popular with all educators and parents. “Why wait until April 23, when there will be no teeth to what you want to do? It’s not going to push our legislators to do anything quickly,” said Tracy Carroll, whose children attend Putnam City public schools.

OEA leadership listened to the rank-and-file: On Wednesday, they moved the walkout deadline to April 2, when students are scheduled to take standardized tests. “I think it shows our voices are being heard as teachers,” Morejon said of the union’s response.

If the legislature refuses to act, Carroll says parents are prepared to support teachers: “I don’t really know any parent that doesn’t support the walkout. We realize that our schools aren’t funded and our teachers deserve more pay.”