Marvin Olasky still remembers the Alamo. Not the famous battle waged there, mind you, but a protest at the site in 1995 against the Texas Commission on Alcohol and Drug Abuse. That state agency was threatening to shut down a faith-based drug rehabilitation program, called Teen Challenge, for failing to employ licensed counselors. In sweltering heat, demonstrators waved signs praising Jesus for delivering them from addiction. They stressed how much money Teen Challenge had saved taxpayers. They weren’t about to let those meddling bureaucrats get in the way of saving lives.

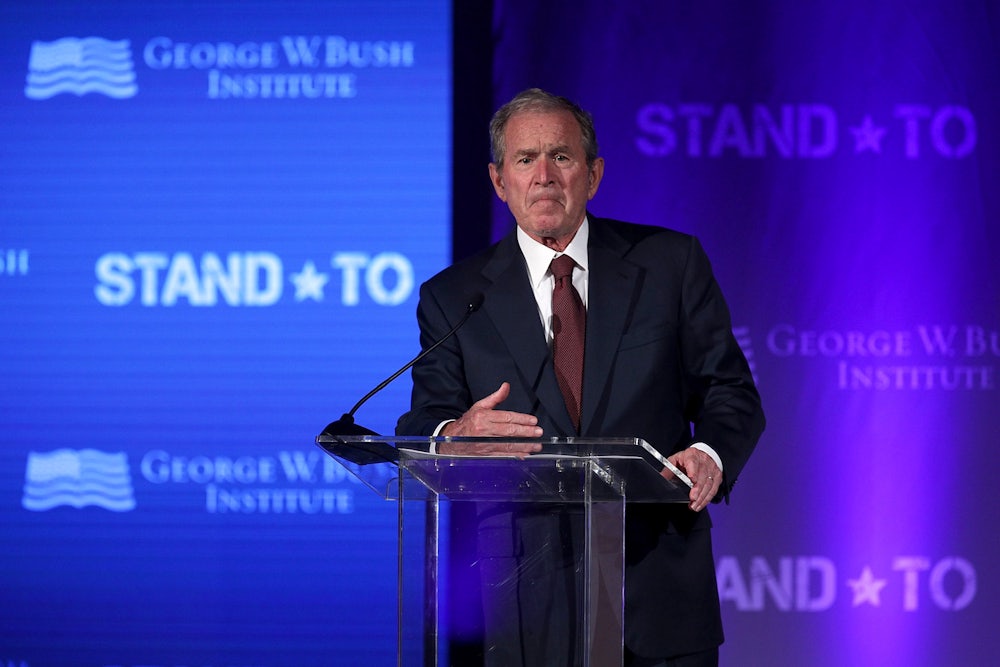

Olasky, now the editor-in-chief of the Christian magazine World, ultimately took up this cause in a Wall Street Journal op-ed. He urged readers to contact the governor’s mansion in Austin, and it wasn’t long before he personally heard from its occupant, George W. Bush, just months into his first term. “I went and had lunch with W.,” Olasky recalled in a speech on Thursday to the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) in Washington, D.C., “and maybe because of his own battle with alcohol, he got it right away. He supported Teen Challenge. He then supported bills that the Texas legislature passed to keep the bureaucrats off the backs of other groups. That, for me, was ‘compassionate conservatism’—liberate what Edmund Burke called the little platoons, what Alexis de Tocqueville called America’s volunteer spirit.”

Bush nostalgia is in vogue these days, and Olasky’s remarks were the latest outbreak—part of an afternoon event he led at AEI on “What happened to compassionate conservatism—and can it return?” “Compassionate conservatism” was Bush’s campaign mantra when he first ran for president in 1999, and it ostensibly became his governing philosophy in the White House. That was thanks in part to Olasky, whom the former president called the “leading thinker” behind the phrase. As Johns Hopkins University political scientist Steven M. Teles wrote in a 2009 National Affairs piece, “The Eternal Return of Compassionate Conservatism,” the goal of this philosophy was “raiding liberalism’s political turf—and stealing Democratic voters.” It “encouraged Republicans to present themselves as allies of the poor and minorities, and to insist that ‘liberal elites’ in the Democratic party were the defenders of ineffective bureaucracies and a morally debased culture. Instead of embracing racial resentment, compassionate conservatism preached, Republicans should rebrand themselves as the party of racial solidarity—the allies of the moralizing agents of the inner cities.” This also had the advantage of strengthening the party’s appeal with white women in the suburbs, who were keen to see the GOP sand down some of its roughest edges.

Bush seemed sincere about compassionate conservatism and genuinely pursued it in some ways. He embraced immigrants and courted minority voters, both as governor and on the presidential campaign trail. He assembled a racially diverse cabinet. He accused congressional Republicans of trying to “balance the budget on the backs of the poor.” In his early White House years, education topped his compassionate-conservative policy agenda, including the landmark No Child Left Behind Act, along with faith-based initiatives and a guest-worker program for undocumented immigrants. But the broader agenda largely fizzled. After September 11, 2001, Bush turned his focus to foreign policy, most notoriously with his war of choice in Iraq. Then, President Barack Obama’s election in 2008 inspired a right-wing backlash and led the reactionary leaders of the Tea Party to reject compassionate conservatism in favor of calls for budget-slashing and “don’t-tread-on-me” libertarianism—all of which gave way to an overt politics of cruelty and white grievance in 2016, which President Donald Trump now embodies. “In some ways, we’ve seen the ascent in recent years of what I suppose could be called ‘callous conservatism,’” Olasky said Thursday.

Hoping for a revival of compassion on the right is understandable. America needs a healthier Republican Party and a morally sound conservative movement. But the term “compassionate conservatism” was tarnished by the Bush legacy, and there’s no evidence its substance is making a comeback anytime soon. In fact, AEI’s discussion speaks to what compassionate conservatism has been since the Bush years—a preoccupation of a small subset of conservative elites without much buy-in from voters. “The idea that the Republican Party should have something to say to African Americans in particular, and Hispanics somewhat subordinately, is a very important idea—not for the conservative base, but for especially the think-tank, public-intellectual side of the Republican Party,” Teles told me. “Their own sense of the legitimacy of the conservative project is related to the idea that it should have something important to say.” But it wasn’t important to the rank-and-file—and it wasn’t necessary to elect Trump.

“In fact, that was sort of the genius of Trump,” Teles said. “He realized that ordinary Republicans don’t give a crap. It’s just not something that’s important to them.”

One of the problems with resurrecting compassionate conservatism is that its proponents don’t always seem to agree on what it is—ideology or strategy. Some conservatives, for example, talk about House Speaker Paul Ryan as a compassionate conservative, because he periodically talks about poverty. But Ryan rose to prominence with the budget-slashing Tea Party politics that explicitly rejected Bush. In its announcement of Thursday’s event, AEI asserted: “Newt Gingrich’s inaugural address as Speaker of the House marked the beginning of a seven-year period in which GOP leadership committed to ‘compassionate conservatism.’ Conservative lawmakers and leaders sought to reform welfare to shift toward an opportunity-based society and avoid stigmatizing those mired in poverty.” It’s true that Gingrich read and admired Olasky in the 1990s, even distributing Olasky’s book, The Tragedy of American Compassion, to freshman lawmakers. It’s also true, as The New York Times reported, that in his first address to the nation, Gingrich declared: “Our models are Alexis de Tocqueville and Marvin Olasky. We are going to redefine ‘compassion’ and take it back.’’ But the notion that Gingrich personally initiated a seven-year commitment to compassion reads like revisionist history to journalist Amy Sullivan, who has covered religion and politics for Yahoo, Time, and The Washington Monthly. “That’s fascinating and ridiculous,” she told me. “It was definitely not a Newt Gingrich priority. I think he constitutionally rejects the idea that conservatism should be compassionate.”

“To me, the big thing here is fear,” Matt K. Lewis, a conservative columnist for The Daily Beast, said. “The economic downturn coupled with 9/11 and Barack Obama’s presidency changed conservatism specifically into a state of fear. Compassionate conservatism works well in an environment of optimism and abundance. When you’re feeling prosperous, you’re much more open to helping other people. ... I think the movement shifted from an abundance mentality to a hoarding mentality.”

Olasky, too, sees 9/11 as a turning point. “War and compassion don’t go together well,” he said at AEI. “War is hell. War is also expensive. ... Many Republicans came to equate compassionate conservatism with more government spending: Compassionate conservatism equals big government; compassionate conservatism is a left-wing thing; phooey on compassionate conservatism.” On this point, Olasky partially blames the Bush administration, which he said “de-emphasized tax credits and stuck with a centralized grant approach” when it came to religious charities. “Instead of fighting bureaucracy, it was building bureaucracy.”

But Sullivan told me there was a more fundamental issue at play. “Compassionate conservatism was, for most folks in the administration, more messaging than anything else,” she said. “Bush cared about it. He had a couple of people in the faith-based office who cared about it. For everybody else, it was kind of a foreign idea, because Republican administrations are not set up to focus on the efficient provision of social services.”

At the dawn of the Trump era, Politico Magazine senior writer Michael Grunwald suggested the new president could fashion his own version of compassionate conservatism, noting that Trump’s “agenda to Make America Great Again is in many ways a big government agenda, with bleeding-heart goals like rebuilding infrastructure and reviving inner cities, as well as get-tough goals like beefing up the military and walling up the border.” Obviously that didn’t come to pass. “There’s no force for compassionate conservatism anywhere in government with any power,” Grunwald told me. “Talking about compassionate conservatism right now is at least a way of highlighting how uncompassionate current governing conservatism has become.”

Perhaps the most devastating blow to compassionate conservatism is that it proved useless as a political strategy in the 2016 Republican presidential primary. Former Florida Governor Jeb Bush ran on his own version of the idea, standing up for inclusiveness and decency in the face of Trump—and voters soundly rejected him. “There’s an argument that a different strand of compassionate conservatism focused more on caring about working-class people left behind by globalization could have been a winning message,” said Tim Miller, who served as Jeb Bush’s spokesman in 2016 and remains one of Trump’s leading Republican critics. But Miller says he’s not optimistic about the GOP adopting an inclusive message on race or immigration, at least not in the short term. “I think the party is drifting away from us on that,” he said.

“We do know what the long-term demographic changes are going to do to the party,” said Tony Fratto, who was deputy press secretary in the Bush White House. “That’s without question. We know that over the next decade and certainly two decades from now, the demographic changes in the country will put the Republican Party in the position of being a minority party unless it changes.” But that reality is completely disconnected from how GOP voters might behave. “It’s not obvious that the party will change in order to win elections,” Fratto said. “They may just lose elections.”

Lewis, though, is more optimistic that the party will get the message. “I still think that eventually it’s going to get to the point where Trumpism is just not going to be mathematically feasible,” he said. “Eventually, you’re going to lose Texas. Not this cycle. Not next cycle. But someday. And sooner than you think.” The key to reform will be Republicans losing in 2018 and 2020. “This is one of those cases in politics where sometimes winning is losing and losing is winning,” Lewis said. “If Trump wins reelection, it postpones the day of reckoning.”

A perennial question in the Trump era is whether the left should hope for the right to have this reckoning, or be even remotely nostalgic for the halcyon days of the early Bush era. Compassionate conservatism is no liberal’s idea of a policy agenda: It is premised on the ineffectiveness of robust government programs, and it brings up a litany of concerns about the separation of church and state. No Child Left Behind—Bush’s signature education policy—fell out of favor on both sides of the political aisle. “Bush’s heart was irrelevant; his policies were typical GOP fare,” The Atlantic’s Peter Beinart wrote in 2015. “In Washington, as in Austin, Bush’s real agenda was massive tax cuts geared to the rich. On his watch, America’s poverty rate rose even before the Great Recession.” Beinart implored the national press not to be distracted by compassionate conservatism’s softer style.

Even Teen Challenge, Olasky’s favorite example of compassionate conservatism, continues to generate controversy. In 2014, Mother Jones reported that the program “considers addiction a manifestation of sin that must be treated with religion. There have been reports of the program performing exorcisms and the internet is full of ‘survivor’ accounts by former clients who found Teen Challenge to be little more than a form of coercive religious indoctrination.”

In retrospect, though, Sullivan said, liberals could have improved compassionate conservatism by being more willing to work with the Bush administration. When you yell, ‘Theocracy,’ and you’re really crying wolf,” she said, “you’ve lost your credibility when real theocrats come to power.” Bush’s compassion agenda also had some widely acknowledged successes, including his work to fight AIDS globally.

At the end of my conversation with Miller, he said it is incumbent upon Republicans like him to keep battling the forces of Trumpism, even if “it’s probably, at least in the short term, a fight that’s quixotic.” I told him that was honorable, if also depressing. “Put that on my tombstone,” he said.