Londoners woke up on April 1 to a troubling statistic: The British capital had more murders in February and March than New York City did, a first in the modern era. There were 37 homicides in London over that period versus 32 in New York, and the cities are comparably sized.

British politicians and commentators have wrestled with how to confront London’s 23 percent surge in stabbings last year and the continued increase in 2018. But this unflattering comparison to the United States—and its well-deserved reputation for bloodshed relative to western Europe—have put the rise into sharper relief.

“It is scandalous that the capital’s murder rate is higher than New York’s,” the Sun declared in an editorial. The Guardian’s Simon Jenkins cited the reversal of fortune as evidence that Britain’s justice system “is in meltdown.” The Daily Mail’s Ross Clark invoked the specter of the 1980s crime wave that killed thousands of New Yorkers. “Back then the Big Apple was known as the ‘Rotten Apple’ and its reputation haunted it for decades,” he wrote on Monday. “London by comparison was a haven. No longer.”

But these latest statistics say more about New York than London. Over the past 20 years, New York has seen one of the most astounding drops in homicides and other major crimes in American history. It’s hard to draw conclusions from New York’s experience and apply them to a foreign city like London. But one area where London can learn from New York is by not imitating its failed overpolicing strategies.

The lesson couldn’t be more urgent. After four young men were killed in knife attacks across the city on New Year’s Eve, London Mayor Sadiq Khan announced a “significant increase in targeted stop and search” by police. “I know from personal experience that when done badly, stop and search can cause community tensions,” he wrote in the London Evening Standard in January. “But when based on real intelligence, geographically focused and performed professionally, it is a vital tool for the police to keep our communities safe.”

Stop-and-search is shorthand for the British police’s power to stop and question a person at any time. Under English law, the officer can also search the person if there are “reasonable grounds” to suspect that the person is carrying something related to criminal activity. Police officers in the U.S. enjoy a similar power. In legal circles, it’s known as “a Terry stop,” but most Americans are more familiar with New York City’s term for it: stop-and-frisk.

Like its American counterpart, stop-and-search is controversial in Britain. Home Secretary Amber Rudd and Metropolitan Police Chief Cressida Dick recently defended stop-and-search’s usage in certain limited circumstances. There’s some evidence to support that view: A 2017 report by the College of Policing, Britain’s professional body for law enforcement, found a “very slight” association between increased use of the practice and lower crime rates on a local level. The group nonetheless advised caution on drawing broader conclusions from their findings.

Also like stop-and-frisk, there are severe racial disparities in the usage of stop-and-search. Its use declined across all ethnic groups after peaking in 2009 and 2010, but those drops haven’t occurred evenly. In 2015, Home Office statistics revealed that black Britons were four times more likely to be stopped and searched compared to white Britons. A sharper drop among whites widened the gap to six times as likely in 2016 and eight times more likely in 2017, the most recent years for which data was available. A recent Criminal Justice Alliance study found that three-quarters of young Britons of color felt their communities were unfairly targeted by the practice. (The disparity is even more troubling given that officials are slightly more likely to find illegal substances on white suspects than black ones.)

Khan, who often tackled racial-discrimination cases as a human-rights lawyer before entering politics, is well acquainted with these issues. When he was a member of Parliament, serving as the Labour Party’s shadow justice minister, he criticized the overuse of stop-and-search. “Police officers must remember at all times that one badly conducted stop and search can undo years of hard work building community relations,” Khan wrote in 2014.

New York’s experience validates those concerns. In 1990, at the peak of a years-long crime wave, there were 2,245 murders there. That decade, as crime began its long, steady decline in New York and across the country, city leaders drew upon the broken-windows theory of policing and aggressively enforced minor offenses. Stop-and-frisk became a key feature of the overall strategy to reduce crime. As with stop-and-search, American police officers are generally free to stop and question people on the street without violating the Fourth Amendment. Those stops can even include pat-down searches so long as the officer has a “reasonable suspicion” that he or she will find contraband.

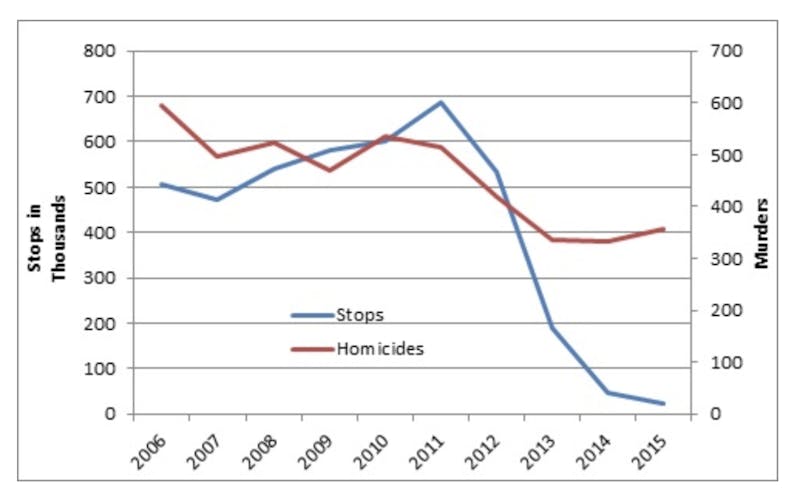

What set New York’s approach to stop-and-frisk apart from other cities was the sheer frequency with which the NYPD conducted the stops. Officers performed millions of them between 2003 and 2013, reaching a peak of 381,000 searches in 2011 alone. Then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg and top NYPD brass defended the policy’s role in fighting crime and noted that officers were required to fill out a form for each stop as an accountability measure.

Those forms provided a wealth of statistical information about who was being stopped and frisked. More than 80 percent of the stops targeted black and Hispanic residents, leading a federal judge to conclude in a 2013 lawsuit that the policy amounted to “indirect racial profiling.” The most disproportionate effects were felt by black New Yorkers, who were targeted by more than half of all stops even though they make up less than a quarter of the city’s population. And despite City Hall’s claims that it was a necessary tactic to keep crime low, city statistics revealed that 88 percent of the searches didn’t lead to arrests or summons.

Nonetheless, stop-and-frisk’s defenders continued to insist that it was a vital tool for keeping New York City safe. “No question about it, violent crime will go up,” then-NYPD Commissioner Ray Kelly claimed as the practice began to sharply decline in 2013. Heather Mac Donald, a Manhattan Institute fellow, warned that “the national trend of declining crime could hang in the balance” if the NYPD lost the racial-profiling lawsuit. Forbes columnist Kyle Smith opined that Bill de Blasio’s successful mayoral campaign meant that New Yorkers had “evidently decided that the crime wave is over and it’s time to get lax about mayhem and disorder.” Donald Trump made the same point with even less subtlety.

If Stop & Frisk is struck down by the pandering NYC politicians, increases in crime & eventual terrorist attacks will be on them.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 22, 2013

In the end, they were proven wrong. A Washington Post analysis in 2016 found no correlation between the decline in stop-and-frisk searches and any increase in crime. “There was a brief uptick last year at the same time as a further drop in the stop-and-frisk count, but in four of the past five years, levels of crime fell alongside the number of stop-and-frisks,” the Post’s Philip Bump wrote. Shootings also continued to decline, he added, undercutting defenders’ arguments that fewer searches would mean more weapons on the streets.

The rise and fall of all kinds of crime in New York mirrored national trends. Even today, however, there isn’t a broad academic consensus on what caused this widespread decline. Scholars generally agree that multiple factors played a role: Some emphasize changing police tactics and other criminal-justice policies, while others focus on socioeconomic influences and demographic shifts. The effects of lead abatement and legalized abortion on crime also continue to be debated. But few still argue that stop-and-frisk played a role in the long decline in crime.

Smith, to his credit, acknowledged his error after the 2017 crime statistics were released in January, showing that there were 286 killings in 2017—a record low for New York. “It’s possible that crime would be even lower had stop-and-frisk been retained, but that’s moving the goalposts,” he wrote. “I and others argued that crime would rise. Instead, it fell. We were wrong.” Other defenders are more recalcitrant. Mac Donald, for example, wrote last fall that rolling back stop-and-frisk and other proactive policing tactics “has not yet affected New York’s ongoing crime decline.” (Emphasis mine.)

Trump admitted no error, either. He defended stop-and-frisk multiple times during his 2016 campaign and even called for it to be adopted nationwide. “We did it in New York, it worked incredibly well,” he said. For Khan, who is familiar with the president’s ill-informed opinions, the lesson could not be clearer.