Mitch McConnell is jittery about the trade war President Donald Trump has launched against China, and with good reason. The Senate majority leader represents the big-business wing of the Republican Party, and Wall Street, if the tumbling stock market is any indication, fears Trump’s protectionism will cause economic pain. “I am nervous about what appears to be a growing trend in the administration to levy tariffs,” McConnell said on Tuesday. “This is a slippery slope, so my hope is that this will stop before it gets into a broader tit-for-tat that can’t be good for our country.”

McConnell isn’t alone. House Speaker Paul Ryan has also fretted over the prospect of a trade war, as have 99 House Republicans who signed a letter in early March expressing “deep concern” over White House plans to raise tariffs on steel and aluminum imports.

Contrast their trepidation with Trump’s bravado. On Twitter, the president sounds like a reckless gambler who’s confident he’s on a winning streak:

When a country (USA) is losing many billions of dollars on trade with virtually every country it does business with, trade wars are good, and easy to win. Example, when we are down $100 billion with a certain country and they get cute, don’t trade anymore-we win big. It’s easy!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 2, 2018

When you’re already $500 Billion DOWN, you can’t lose!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 4, 2018

It’s hardly surprising that a rift has opened up between Trump and party leaders; the surprise is that it took this long. In 2016, Trump ran as a heterodox Republican on a platform of issues that set him apart from conventional Republicans like McConnell and Ryan: He promised to be a protectionist on economics, an ultra-hawk on immigration, and a unilateralist on foreign policy.

But these differences have turned out to be mostly rhetorical. In practice, Trump, who is notoriously disengaged with policy, has gotten along well with congressional Republicans. To be sure, Trump has governed as an immigration hardliner, but those hurt by his policies—undocumented immigrants—are low on the GOP’s list of worries. On foreign policy, he has barked out ideas like withdrawing the United States from Syria, but his staff continues to uphold the status quo. Despite Trump’s personal solicitude of Vladimir Putin, his administration’s policies on Russia have been hawkish.

But Trump’s trade policies are threatening his modus vivendi with the GOP. His belief in protectionism is deeply ingrained, a conviction he’s held for decades even as he’s shifted on virtually everything else. And his eagerness to enact the policy now proves as much. In recent weeks, Trump has become unleashed: convinced that he knows best, and jettisoning staffers and even cabinet members with whom he disagrees. Feeling more empowered than ever, he’s decided that trade is the issue with which to assert himself in policymaking.

Congressional Republicans are helpless to stop Trump, because the president enjoys wide latitude on trade. “Congress could stop Trump from imposing the tariffs tomorrow if it wanted to. The Constitution gives the legislative branch explicit authority ‘to regulate commerce with foreign nations,’” Russell Berman wrote in The Atlantic. “But over the last 50 years, Congress has delegated the bulk of its trade power to the president, and there isn’t much expectation that it’ll wrest it back anytime soon.”

Trump’s trade policy is a test for congressional Republicans—and Trump has shown he’s willing to attack lawmakers from his own party whom he views as insufficiently loyal. Democrats, meanwhile, have the luxury of taking varied stances on trade. Some, like Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, are supporting Trump’s position as a way to solidify support from the protectionist wing of their party. Democratic candidates running in districts hurt by China’s retaliatory tariffs, meanwhile, are using trade as a wedge issue.

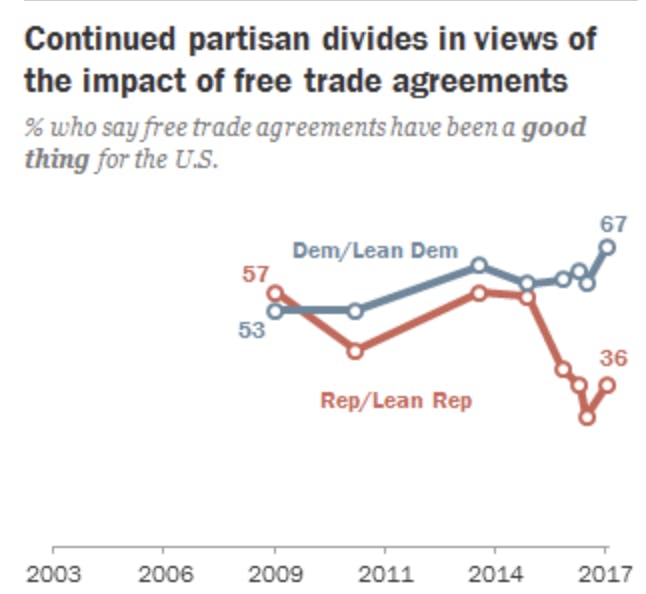

The deeper problem for Republican lawmakers is that the base of their party is closer to Trump on the issue. As polling from the Pew Research Center shows, the percentage of Democrats and Republicans who support free trade was roughly even until three years ago, when support began to rise among Democrats and fall among Republicans. Trump’s new economic advisor Lawrence Kudlow exemplifies this shift. A month ago, while still a pundit, he wrote, “Trump should also examine the historical record on tariffs, because they have almost never worked as intended and almost always delivered an unhappy ending.” Now in the White House, Kudlow was asked if a trade war would hurt the U.S. “No,” he said.

Given that only a third of Republicans and Republican-leaners believe that free trade has been good for the country, and the fact that Trump is more popular with the GOP base than congressional leaders like McConnell and Ryan, it’s likely that the party establishment won’t try to stop Trump’s trade war. That surrender will come at the price of alienating big business, but GOP leaders have little choice. They belong to the party of Trump now.