On last Sunday’s episode of The Simpsons, Marge and Lisa had an awkward mother-daughter conversation about a children’s book that Marge loved as a child, but which, upon revisiting, turns out to have an embarrassing colonial subtext. “Well what am I supposed to do?” Marge asked. “It’s hard to say,” Lisa said. “Something that started decades ago and was applauded and inoffensive is now politically incorrect. What can you do?” Then Lisa looks at a framed picture on her nightstand of Apu Nahasapeemapetilon, an Indian-American character at the center of a debate over racist stereotyping on the nearly 30-year-old show.

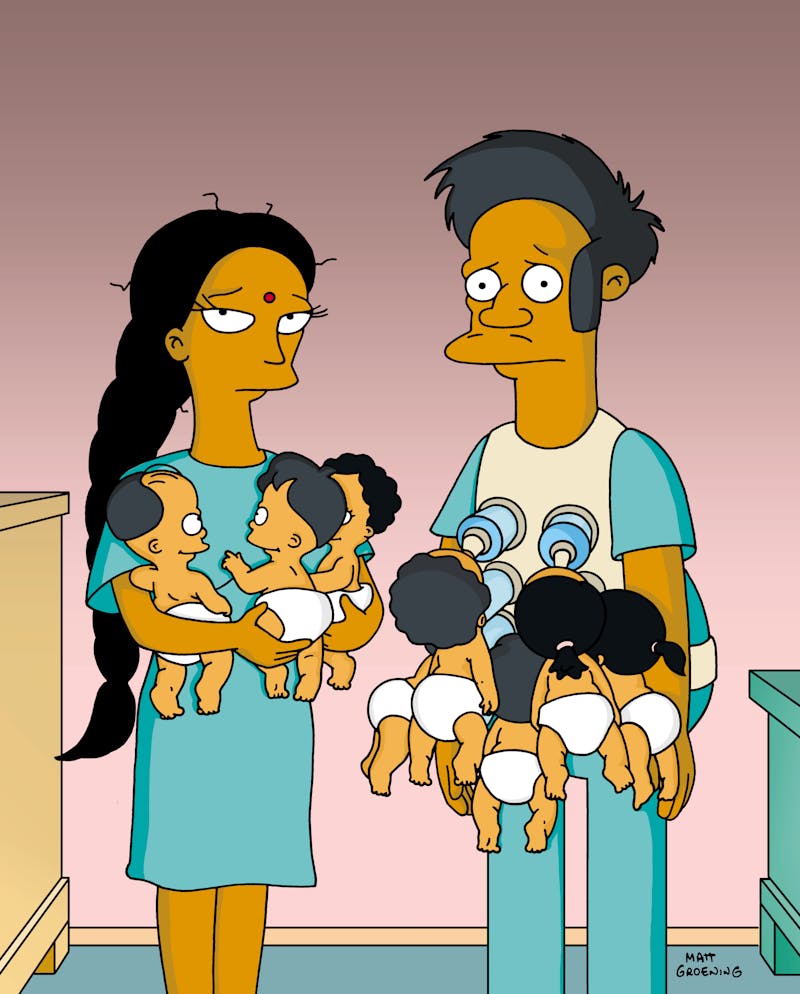

Apu has been a Simpsons fixture from the start, and is far and away the most famous Indian-American character in popular culture. Like many of the show’s characters, he’s a broad stereotype, a miserly convenience store owner who speaks with a pronounced accent. There have been murmurs of criticism about Apu since his appearance in the first season, but he’s more controversial than ever due to The Problem With Apu, a documentary last year by Hari Kondabolu, a New York–born comedian who is the child of Indian-American immigrants. The scene in Sunday’s Simpsons episode was clearly a response to Kondabolu.

#TheSimpsons completely toothless response to @harikondabolu #TheProblemWithApu about the racist character Apu:

— Soham (@soham_burger) April 9, 2018

"Something that started decades ago and was applauded and inoffensive is now politically incorrect... What can you do?" pic.twitter.com/Bj7qE2FXWN

When I first heard about the film, I was dismissive. Like Kondabolu, I’m part of the desi diaspora and a Simpsons fan. I was born in India and grew up in an immigrant milieu in Toronto. My family even ran a convenience store in the 1970s and early 1980s. I never had a problem with Apu. I recognized he was a stereotype, of course, but saw him as affectionately done, in the manner of some of the broadly depicted Jewish characters on Seinfeld and Curb Your Enthusiasm.

Nor am I the only desi who is indulgent of Apu. Some writers have been similarly inclined to give Apu a pass.

“Kondabolu’s complaints are not without some basis,” radiologist Pradheep J. Shanker wrote this week in National Review. But he insists that racism to Indian Americans pre-dates Apu, and would exist even if the character had never existed. “I grew up largely before The Simpsons ever aired. Was I exempt from the random racial epithet? Of course not. And this is where Kondabolu’s complaints are so ridiculous. Racists and bigots will find something to use to denigrate the ones they hate, regardless of the available source material.”

I had heard similar arguments before watching The Problem With Apu, and not long ago would have generally agreed with them. But watching the film, and listening to interviews with Kondabolu and other younger desi, convinced me I was wrong—and highlighted an important generational shift in the desi diaspora.

Older desi, not just me and Shanker but Kondabolu’s own parents (who joke about his “Apu hair”) see Apu as a minor inconvenience. But younger desi, including many comedians and actors that Kondabolu spoke to for his film, have experienced a very different reality. They grew up in a world where The Simpsons was a pervasive part of popular culture and Apu the only Indian-American character everyone knew. They were taunted and bullied in school, with Apu’s name and catch-phrase (“Thank you, come again.”) used as an insult. It’s their lived experience of growing up with Apu that shows why this minor character is so pernicious.

Apu is now a slur more than he is a character. It’s true, as Shanker argues, that other slurs existed before Apu. But those slurs didn’t carry the cultural authority of The Simpsons. When a bully calls an Indian American “Apu” or says to them, “Thank you, come again,” he isn’t just demeaning the person by himself (though that is wrong enough); he’s using The Simpsons to justify his contempt. As The Problem With Apu showed, Apu makes desi kids feel insulted not just by individuals, but by American culture at large. That’s why the film changed my mind. It featured testimony about Indian-American experiences I wasn’t aware of. I was bullied for being Indian American, as Kondabolu’s subjects were, but I wasn’t bullied with language from one of the most famous shows on TV.

The common defense of Apu is that The Simpsons has many stereotypes (the Italian Fat Tony, the sometimes-Jewish Krusty the Clown, the Scottish Groundskeeper Willy). But none of these characters exist in a cultural reality where they are the only representative of their ethnicity: there are myriad Italian-American and Jewish characters on TV, but for many years, Apu stood as a singular representative of desi culture. That’s slowly starting to change with shows like Mindy Kaling’s The Mindy Project, but these programs haven’t yet had the cultural impact of The Simpsons.

There’s a big difference between the self-deprecating ethnic comedy of Kondabolu and Kaling, which belongs to a tradition of Richard Pryor and Jerry Seinfeld, and having a white man do an Indian accent (as Hank Azaria does for Apu). As Kondabolu argues in a conversation with Whoopi Goldberg, there’s an undeniable element of minstrelsy in Apu. The documentary makes this clear by juxtaposing Apu’s clowning—dancing with a cane, for instance—with blackface antics of early 20th century films. In both blackface and Apu, the main character is a loveable but silly clown, defined by an accent. When I used to watch The Simpsons, I thought Apu was at least more affectionately intended than Peter Sellers’s brown-face character in the movie The Party. But one of the disheartening revelations of Kondabolu’s documentary is that Azaria modeled his accent off The Party.

It’s true that the use of ethnic stereotypes is an almost inevitable part of comedy. It’s also the case that these stereotypes often get re-interpreted or challenged by later generations. In 1900, the cartoonist Fredrick Opper created Happy Hooligan, a hapless Irish-American hobo. Stereotypes about the Irish, often depicted as having simian features, were common at the time. Homer Simpson himself is part of this visual tradition, but in keeping with changing ethnic attitudes is seen as generically white.

Writing in the journal The Independent in 1901, Opper defended using stereotypes as part of the logic of cartooning, which he encapsulated in the phrase “Caricature Country”:

Colored people and Germans form no small part of the population of Caricature Country. The negroes spent much of their time getting kicked by mules, while the Germans, all of whom have large spectacles and big pipes, fall down a good deal and may be identified by the words, ‘Vas iss,’ coming out of their mouths. There is also a good sprinkling of Chinamen, who are always having their pigtails tied to things; and a few Italians, mostly women, who have wonderful adventures while carrying enormous bundles on their heads. The Hebrew residents of Caricature Country, formerly numerous and amusing, have thinned out of late years, it is hard to say why. This is also true of the Irish dwellers, who at one time formed a large percentage of the population.

Opper was being either coy or dishonest in saying he didn’t know why Irish and Jewish (“Hebrew”) caricatures were disappearing: A new generation of Irish-Americans and Jewish Americans wasn’t so indulgent of these stereotypes.

The same has happened with many other minority and immigrant groups. These days, Amos ‘n’ Andy is remembered as a prime example of minstrel comedy: characters originally created on radio by white actors who adopted broad black dialect that played up a lack of education. But as William and Mary historian Melvin Patrick Ely pointed out in his 1991 book The Adventures of Amos ‘n’ Andy, the reality is more complex. When the program first aired on radio, it was beloved by white audiences, but polarized black ones. Some black listeners hated the show from the start. One letter writer complained in 1930 that the show taught the world “that the Negro in every walk of life is a failure, a dead beat and above all shiftless and ignorant.” But the show also got fan letters from many black readers who were grateful to receive any representation and who credited the actors with doing realistic dialect. “Those fellows must have been reared with colored people,” ran one fan letter.

But as Ely shows, what was acceptable in 1928 became intolerable by the early 1950s, especially in the wake of political activism led by groups like the NAACP. African-Americans, Ely argued, had “become impatient for change and quicker to see insults in white behavior and gestures that had once been ‘endured’ in silence. America as a whole, and black America in particular, had changed, while Amos ‘n’ Andy—a pathbreaker in 1928—still portrayed Andy and Kingfish much as it had twenty-three years earlier.”

In The Problem with Apu, Dana Gould, a writer and producer for The Simpsons, acknowledges that Apu is “anachronistic.” That is true of many ethnic characters in the history of humor and cartooning, and for similar reasons. Amos ‘n’ Andy and Happy Hooligan became anachronistic because the communities they caricatured acculturated and found their political voice. Irish immigrants gave way to the American-born Irish, who had less tolerance for ethnic jokes and felt empowered to speak up. Amos ‘n’ Andy, meanwhile, was really a comedy about the first generation of African Americans who left the rural South for a life in the urban North. As those migrants settled in cities and became politically active, they too began to challenge how they were represented in pop culture.

Of the many problems with Apu, perhaps the most worrying one is that, as a cartoon, he’s immortal: an offensive caricature from 1989, given new life every Sunday night on Fox. He can be drawn forever and never change. But this problem is also relatively simple to solve. You don’t have to fire a cartoon. (You don’t even have to fire the voice behind it: Azaria does many other characters on The Simpsons.) You can just redraw it, literally or figuratively. Apu doesn’t have to work at the Kwik-E-Mart, and he doesn’t have to patank. This Indian-American stereotype is increasingly unfamiliar anyway. The least The Simpsons could do is update it by making Apu a rich convenience-store magnate with an American accent.

An Apu makeover would solve the problem for the show going forward, but the original offensive version of the character will have a long half-life in syndication re-runs, not to mention the zombie existence provided by YouTube and gifs. In that sense, Apu is a problem without any short term solution. The best we can hope for is that as an anachronism, he’ll go the way of Happy Hooligan and Amos ‘n’ Andy as he’s crowded out of the cultural memory by newer art, this time created by Indian-Americans like Kaling and Kondabolu. The most effective answer to flawed art is different and better art. As The Problem With Apu hearteningly demonstrates, there’s a rising generation of desi ready to make that art.