The first militant act of the Women’s Social and Political Union was a dry-mouthed spit, “a kind of pout,” from 25-year-old Christabel Pankhurst into the face of a police officer, the only physical assault she could manage while her arms and legs were restrained. Her action, carried out in Manchester in 1905, got her labeled a “spitfire,” which pleased her, and arrested, which pleased her even more. The publicity brought the fledgling group, spearheaded by Christabel’s mother Emmeline and her sisters Sylvia and Adela, to national prominence, and launched their nine-year struggle for the vote—suspended in 1914 for the duration of World War I, and partially victorious in 1918, when property-owning women over the age of 30 won the vote in Britain.

Diane Atkinson’s Rise Up, Women is an exhaustive, 500-page account of that struggle. There are hundreds of mini biographies packed in here, and more often than not they begin with an unconventional girl, working to support herself, sometimes married to a free-thinking, liberal-leaning man, who sees injustice in her life and her world and looks around for a way to change it. She goes to a meeting, makes like-minded friends, and in turn starts to recruit new members in her own circles, and to consider how far she’s willing to go for the cause. The cumulative effect of these stories is a gathering wave, as more and more women enlist in the WSPU’s campaign of publicity-seeking civil disobedience and the male authorities struggle to respond.

The most important and revolutionary tactic of the militant movement was to turn women’s bodies—supposedly passive, pliant, and protected—into its battleground. Suffrage foot-soldiers attacked politicians and police officers with fingers, feet, or weapons, and drove men who believed themselves chivalrous to beat women, kick them, and shove them to the ground. In Holloway, the largest women’s prison in Western Europe, the imprisoned protestors refused food and drink to the point of collapse. Nurses knelt on their chests while doctors forced catheters down through their noses and mouths and pumped liquid eggs and milk into their stomachs.

The movement’s martyr, Emily Davison, was kicked and trampled to death by the King’s horse in the 1913 Epsom Derby, an apparent act of self-destruction that may, in fact, have been accidental. The following year, Mary Richardson went to the National Gallery with an axe up her sleeve and slashed Diego Velazquez’s painting of a nude, reclining Venus, landing several gashes in the goddess’s back. She explained that she took aim at Venus in order to protest the way the nation celebrated the physical beauty of a mythical woman even as it abused and vilified the spiritual beauty of Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst.

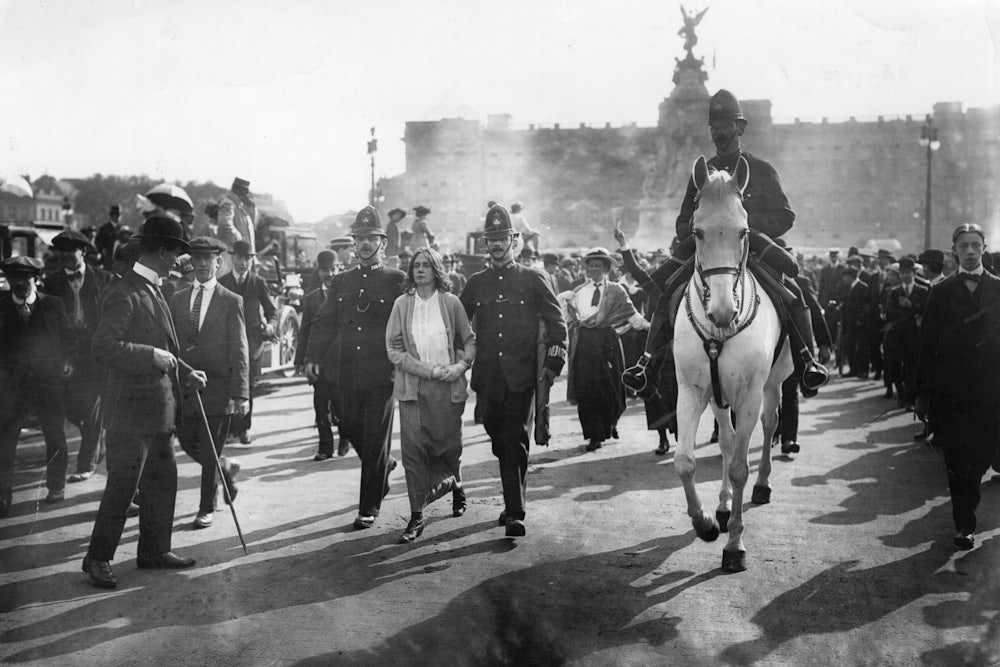

As the campaign gained strength, the opposition worked to dehumanize and demonize the “suffragettes”—a belittling nickname bestowed by the Daily Mail, but which the protestors reclaimed and embraced. An avalanche of cartoon postcards, which Atkinson likens to “tweets of their day,” stereotyped them as ugly spinsters, as brattish children, as geese and cats and men and monsters—anything to undo their femininity and render them acceptable targets. Even though the protestors primarily attacked buildings, breaking windows and setting fires, the goal was always to draw the state’s violence down on their bodies, and to shock men into seeing what was at stake.

Whereas an earlier generation of activists had put their names to petitions, the twentieth-century suffragettes put their bodies in the streets. London’s first major suffrage rally took place in June 1908, when 30,000 women converged on Hyde Park: Lancashire mill girls, East End factory hands, teachers, students, and wealthy activists. Sylvia Pankhurst described the joy of subsuming individual identity into the crowd, as banners waved to make the point of what the women wanted: “Not chivalry but justice.” The usually hostile press rhapsodized over the spectacle. “I am sure a great many people never realized until yesterday how young and dainty and charming most leaders of the movement are,” wrote the Daily Mail.

While there were plenty of veteran activists in the movement (Atkinson traces the fight back to the 1850s, when it overlapped, as it did in the United States, with the abolitionist movement), the WSPU in the early 20th century was a self-consciously youthful organization. On both sides of the Atlantic, the dawning of the twentieth century, and the coming of age of girls born in the 1880s and 1890s, helped push these long, long fights to their victories. The death of Queen Victoria in 1901 and nine years later of her son Edward, bloated and decadent after decades in waiting, marked, in Britain, decisive breaks with the past.

Virginia Woolf’s declaration that “human character changed” somewhere around December 1910 was, on the face of it, a flamboyantly overstated reaction to an art exhibition organized by her friends, but it named something people felt to be true. Woolf and her siblings and friends were saying things to each other and in print that had never been voiced in mixed company. In their scruffy, bohemian corner of London they shared new ideas for living and working, just as in New York at the same time, young men and women with literary aspirations and radical politics were gathering in Greenwich Village. Close by, in factories and crowded slums, young working women also grasped the power of collective action for change.

On both sides of the Atlantic, the suffrage and labor movements were intimately entwined. Atkinson’s book helps put working-class women back in their rightful place at the center of the British suffrage story—women like Annie Kenney, the daughter of progressive and self-educated Yorkshire laborers, who went to work in the local mill at the age of ten and later became a protégée of the Pankhursts and a WSPU leader. In 1907 in New York, Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s daughter Harriot Stanton Blatch, who had spent 20 years in England, formed the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women, to involve working-class women in the suffrage fight. The grassroots campaigns led by garment workers, mostly young immigrants, included boycotts and marches aimed at improving safety and working conditions; they were fired up by the tragedy of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire in 1911. It was these young women’s willingness to take to the streets and risk harassment, abuse, and arrest, that convinced the suffrage leaders that marches could be an effective protest strategy.

When King George V was crowned in 1911, Britain was awash in a spirit of uncharacteristic optimism for the future. The suffragettes paraded again that June in even greater numbers, behind a 19-year-old figurehead named Margery Bryce, mounted on a white horse and dressed as Joan of Arc. The following year, across the ocean, a young lawyer and industrialist’s daughter named Inez Milholland rode a horse through the streets of New York, in costume as one of Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, at the head of another parade that likewise aimed to showcase the force of the movement through the energy, spirit, and sheer numbers of its members.

The cross-fertilization of rhetoric and tactics between the British and American movements was extensive, although the Americans shied away from arson and window-smashing. The Pankhursts made several separate trips to America and were greeted as celebrities by audiences there. In 1911, Sylvia Pankhurst undertook a three-month speaking tour from New York across the Midwest, lending her support to a pending, and unsuccessful, suffrage bill in Iowa. Two years later, the family’s notoriety had grown enough that her mother Emmeline was detained at Ellis Island for two days, and only released on the intervention of Alva Belmont, the wildly wealthy bankroller of suffrage in New York. In Louisville, Mrs. Pankhurst made her argument that militarism—“deeds not words”—was a strategy whose roots lay in the “record books of man’s enfranchisement,” which inspired American suffragists to draw parallels with their country’s founding revolution.

Lucy Burns from Brooklyn and New Jersey Quaker Alice Paul, co-founders of the National Woman’s Party, took the most direct inspiration from the confrontational British suffragettes. They met at a police station in London after protesting outside Parliament with the WSPU, and both were imprisoned and force fed several times. In Washington DC, they and their followers picketed the White House, provoking arrest and enduring hunger strikes and force feeding at the Occoquan Workhouse in Virginia. Paul also adopted one of the WSPU’s most politically controversial tactics, of siding with candidates whose parties opposed women’s suffrage, with the aim of forcing politicians who were nominally sympathetic to the cause to put their votes where their promises were.

The vote, for these daughters of the new century, was a tool and a weapon for a range of fights: for labor reform, for global peace, for racial and religious equality, for birth control and easier divorce and widened access to universities and professions. For many, it was a way to change the political tenor of the country, to elect socialist and Labour candidates, and to overthrow a system that had been run by and for elite white men for far too long.

History is still not quite sure what to do with the militant suffragettes. A century on, the principle of women’s suffrage is familiar and mostly uncontroversial, so it is easy to feel that victory was inevitable, that the stakes were lower than they seemed at the time, and hence that the tactics of the militant WSPU in Britain and NWP in America were extreme or misguided. But in the midst of the fight, with its regular disappointments and its grinding daily effort, winning the vote felt anything but preordained. And the fights went on: to use the vote, to run for office, to enshrine women’s equality into law. Alice Paul introduced the first Equal Rights Amendment in 1923, and fought for it, unsuccessfully, up to her death in 1977.

Within the movement, there were regular rifts over tactics, goals, and ideals. (Atkinson’s index for each Pankhurst family member contains several entries for “breach with… .”) In both the United States and Britain suffragists were bitterly divided over World War I, with some members of the movement choosing to support the war in exchange for the rights of citizenship, to the horror of those whose commitment to peace was as strong as their desire for equality. Most notoriously, the push to ratify the 19th Amendment in the American South involved ugly compromise with the forces of white supremacy. Many suffragists publicly or privately argued that the white women’s vote could be a bulwark against the political advancement of populations of color.

A patchwork of compromises in practice, women’s suffrage, when it was won, was undoubtedly a sweeping moral victory. Women fought and suffered and died, and out of their suffering, out of their rage, we got something we still value, that ought not to be taken for granted. But when suffrage is merely a symbol, we can lose sight of its connection with other fights, other rights that women still haven’t won: fair pay for our work, freedom from harassment, full control over our bodies and the size of families. Looking back on the suffrage fight now, a hundred years on, we should not simply celebrate the victory, but remind ourselves how jealously men guarded the reins of power, and how difficult it was—and remains—to wrest them away.