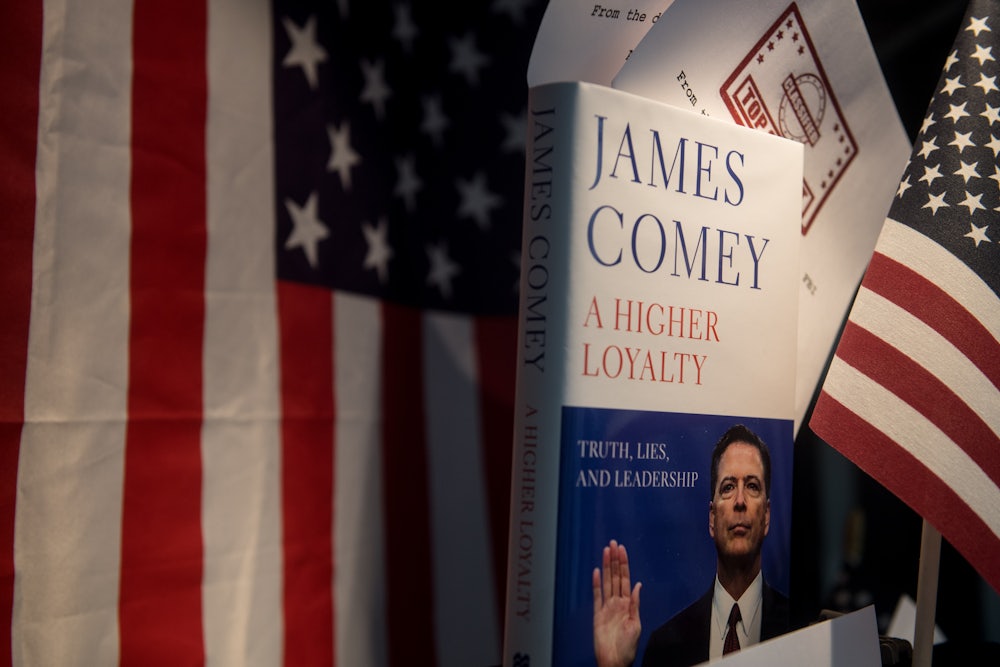

Whatever former FBI Director James Comey may have expected when he set out on a tour to promote his book, A Higher Loyalty, he didn’t find himself on smooth waters. He had an enviable itinerary: a prime time hour on ABC for openers, followed by USA Today, Today, NPR, Good Morning America, Stephen Colbert’s late-night show, The View, and interviews with CNN’s Jake Tapper and MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow. (Clearly his publisher knew that there was no point in trying to sell Comey’s book to conservative audiences, and that the priority was to market it to women, who are known to read more books.) Inevitably, while the book is almost entirely about Comey’s personal and professional biography, the interest on his publicity tour was in his role in the 2016 election—did he cost Hillary Clinton the presidency?—and his turbulent relationship with Donald Trump.

The strange thing about Comey is that, in the course of writing the book and selling it on TV, he has changed his story about his crucial decision to re-open the investigation into Clinton’s email server. He has also said that he wished he’d written certain parts of the book differently, or not at all. His physical description of Trump—the “slightly orange” skin, the “impressively coifed” hair, etc.—and the reference to the size of Trump’s hands were widely criticized as cheap shots, even “bitchy.” By the time he appeared on Colbert’s Late Night, Comey said he wished he could take out the two offending paragraphs. His sentence on Trump’s hands is revealing of Comey’s method of trying to please all sides and his occasional slipperiness (hidden behind his earnest expression): “It was smaller than mine, but did not seem unusually so.” What is the point of that? He wasn’t required to mention Trump’s hands, a lurid knickknack from the campaign that had been essentially dropped.

Like much of what he says about his most controversial acts, Comey’s efforts to please all ended in pleasing just about no one. Both sides have their grievances with Comey and don’t particularly like him. I almost began to feel sorry for him.

Plaintively, Comey tried to explain that he was simply following his publisher’s admonitions to “bring the reader with you,” and, shucks, he’d also given detailed descriptions of other figures in the book. In fact, Comey’s book is well written (if anyone cares) and he shows a certain flair for color. I have little doubt that Comey’s publisher, like most of their breed, encouraged Comey to put in the little shots at Trump. Still, it was Comey who did it. But I have more sympathy for Comey on this matter than his strongest critics do. What if he hadn’t included a description of Trump? He’d have been assailed for that, too.

I see Comey as someone who dedicated his life to public service and trying to do the right thing, but who played the angles a bit too much. For example, he couldn’t just recommend that Clinton not be prosecuted over her email server, but had to publicly upbraid her as well, which was most unusual. It was if he felt that he had to mollify Republicans and FBI agents who felt that she should have been charged.

In fact, Comey had shown questionable judgment in taking charge of the case after then-Attorney General Loretta Lynch recused herself over her tarmac meeting with Bill Clinton shortly before the FBI was to interview his wife. The proper approach would have been to turn the issue over to the deputy attorney general or the head of the Justice Department’s criminal division. Comey explained on tour that public faith in the Justice Department and the FBI “is all we have,” and that it would have lacked credibility if the Democratic-led Justice Department made the announcement that the case against Clinton was closed. Perhaps, but in making the announcement himself he broke a longstanding norm, since the FBI traditionally investigates and merely recommends to Justice whether prosecution is in order.

Here’s where Comey got himself on slippery ground, on one of the most important decisions he made in the course of the presidential campaign. In his book Comey refers to an unverified rumor, thought to have originated with Russians messing around in the presidential campaign, that Lynch had told the Clinton camp that Justice would go easy on her. If true, this would indeed have been scandalous but there was no evidence that it was true. Yet Comey has used this rumor to justify his taking the Clinton investigation away from the Justice Department and jumping from his role as investigator to that of prosecutor. But when Rachel Maddow pressed him on this in her Thursday night interview, Comey said, “I did not believe that she [Lynch] had acted in any way inappropriately.” Smear offered and ostensibly retrieved.

Comey, by his own account, thought the existence of the rumor was reason enough to break the norms surrounding the announcement of prosecutorial decisions. He excused the self-induced expansion of his role for fear that Clintion’s exoneration—a decision that, as Comey said, no serious prosecutor would disagree with—would be seen as a partisan decision. He told Lynch that he was going to make the announcement just minutes before he did.

By my count, Comey has offered at least three different explanations of why he announced eleven days before the election that he was reopening the case of Hillary Clinton’s use of a private email server. In his book he explains that he made the announcement to protect the presumed President-elect Clinton from disclosure that she’d been secretly under investigation at the time of the election, which he feared would “delegitimize” her presidency; then he also maintained that he and Lynch had said that “there’s no there there,” and so they had told the American people “something that may no longer be true”; and at the time when Comey sent the letter to Capitol Hill that the investigation of Clinton was being reopened, his allies spread the point that Comey had told the House Republicans that he’d let them know if anything new came up.

But according to Matthew Miller, a spokesman for the Justice Department when the Democrats were in power, Comey hadn’t exactly told them that. According to Miller, in response to a question by a congressman of what he would do if he came across any new information, Comey replied, “I’d take a look at it.”

Comey has also insisted that his staff had told him that there wasn’t time to check the emails found on Anthony Weiner’s laptop, which turned out to be copies of emails that had already been inspected and that Weiner’s then-wife and Clinton confidante Huma Abedin had stored there. Furthermore, Comey has said both that his agents didn’t have time to get a warrant to inspect the emails and that they had gotten a warrant. But still, he argued, there were thousands and thousands of emails. However, a quick sampling would have indicated that these emails weren’t new.

People can argue down through the ages whether Comey cost Clinton the election. When the outcome was determined by 80,000 votes across three states—Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania—any number of factors could have made the decisive difference. It can also be validly argued that if Clinton had been a better candidate she wouldn’t have been so vulnerable to the effect of Comey’s action.

Another example of Comey’s pliability on book tour arose about his view on impeachment. In his appearance with ABC’s George Stephanopoulos, the most skilled of the interviewers Comey faced, Comey admitted that, in giving his famous memos about encounters with Trump to a friend, with instructions to leak them, he was trying to bring about a special counsel. But when asked whether he thought Trump should be impeached, Comey replied that he was against that because it would “let the American people off the hook.” His preference, he said, was that the people vote Trump out of office in 2020—thus betraying a complete lack of understanding of the point and purpose of the impeachment clause in the Constitution. The Founders weren’t content with a situation that Comey advanced: that no matter how wrongly or even dangerously a president may be behaving, the public would be stuck with him until the next election. Recourse in such a situation is precisely what impeachment is about.

Perhaps due to the feedback from friends—Comey has several close, admiring friends, and devoted FBI agents—Comey adjusted his response when Colbert asked him about it. He said, “The law and the facts will drive whether there’s an impeachment process.” In trying to explain what he had meant in his response to Stephanopoulos, Comey added, “In a way, that would short circuit something we need: We need a moment of clarity and inflection in this country.” Whatever that means, Comey is impatient with people who didn’t vote in 2016 (which might have made a difference in the outcome), and he said to Colbert that he hoped that “the great middle will get off the couch and get out of their busy lives and say, ‘The values of our leadership matters.’” This fuzzy bromide is Comey’s message. But if Comey thought that his book would set off such a discussion there’s no evidence of that.

Comey executed a number of walk-backs, which suggested a lack of certainty on the part of this seemingly proud man. In addition to saying on tour that he wished he hadn’t written the physical description of Trump, Comey said that he probably shouldn’t have used the words “extremely careless” in chiding Clinton about her handling of emails. That would have been a pretty big difference.

He also leaves out critical factors understood at the time that led to his highly unusual ex cathedra comments, as well as his later announcement that he’d reopened the case. The main thing he omits is that in both cases he was under strong internal FBI pressure to be tougher on Clinton than he was inclined to be. Despite the myth that FBI agents are strictly after the facts, they also have opinions and there was a strong anti-Clinton contingent in the FBI headquarters in Washington and an even stronger one in the New York bureau, where she was known to be especially hated. Apparently long forgotten, until Maddow brought it up, is that Rudy Giuliani, who is close to the New York bureau, signaled aloud shortly before the email case was reopened in October of 2016 that a big surprise was coming that would affect the campaign. After Comey announced the explosive news that the Clinton case was to be reopened, Giuliani said that that’s what he’d been referring to. So a reason widely surmised at the time was that agents in the New York bureau were planning to leak the fact that an investigation would be made of the emails in Weiner’s laptop if Comey didn’t announce it.

In his interview with Maddow, Comey said that fear of a leak out of the New York bureau had no impact on his decision and that at the time he’d instigated an investigation into leaks out of the New York bureau—the result of which is expected to be announced next month.

Giuliani, of course, is now joining Trump’s legal team and in his overweening immodesty has said that he’ll get the Mueller investigation finished in two weeks. Comey, who describes Giuliani vividly in his book, said on tour that he wonders how the imperial natures of both Trump and Giuliani will mesh. Current events also whanged into Comey’s book tour when House Republicans, still determined to shut down the special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation, demanded and received copies of the memos Comey wrote of his troubling encounters with Trump. (It was a sign of the browbeating the Justice Department had been taking from Trump and his congressional allies that it set a precedent for surrendering to Congress documents crucial to an ongoing investigation.) Which, of course, were promptly leaked to the public. Though the memos had already been described by Comey in testimony before Congress and in his book, the Republicans are now trying to distort them into something scandalous.

It’s worth adding that Comey has said on the tour several times that there can be no such thing as shutting down the Mueller investigation: that even if Mueller and the entire Justice Department were fired, “the culture” of the investigatory forces in this country would keep the inquiry going.

The problem for Comey is that revenge books are problematic. If the author is justifying his own most controversial actions, any discussion of them will reopen those issues. The justifications, in some instances new ones, leave the author vulnerable to renewed challenges of the actions in question as well as the justifications themselves. If, further, the author is a formerly powerful figure, and his target is a sitting president, he and his book will draw an unusual amount of scrutiny. Comey has said that he understood that there would be criticism of his book, but it’s unclear that he was ready for the crossfire it’s been receiving from both Democrats and Republicans.

My impression of Comey is of an earnest, decent man, a bit tone-deaf but not without a sense of humor. (Comey noted in his book something that has gone largely unremarked upon: that he’d never seen Trump laugh.) Comey’s pride—and he has had accomplishments to be proud of—sometimes slips into moralizing that puts many people off. (On the tour he was obliging almost to a fault. Seemingly struggling to be liked, he habitually said to his hosts: “That’s a good question” or “That’s a great question.”) To his credit, Comey indicated in his interview with Stephanopoulos that he’s aware that he can come across as self-righteous, and so he made sure to have people around him who would question and challenge him. But Comey shed a layer of dignity by letting his anger at Trump get the better of him, in the end undercutting his case against the president. Robert Mueller, for example, wins our estimation by keeping quiet and simply going about his business. Were he to be fired, I would expect Mueller to refrain from writing a revenge book.

In playing the angles, in assessing the likely political impact of various decisions he had to make, Comey not only got it wrong, but also strayed from the prosecutors’ directions to “go by the book.” And each decision got him in lasting trouble, to which he has responded with self-pity and excuses. Comey was ill-used by Trump, who not only fired him but also sought to humiliate him, ordering that the deposed FBI director, who learned of his firing from a televised report while he was speaking to FBI agents in Los Angeles, couldn’t return to FBI headquarters to collect his belongings. While his firing might have made Comey a lasting sympathetic figure, he got in trouble with the larger populace for what he didn’t do: stand up and take the heat.