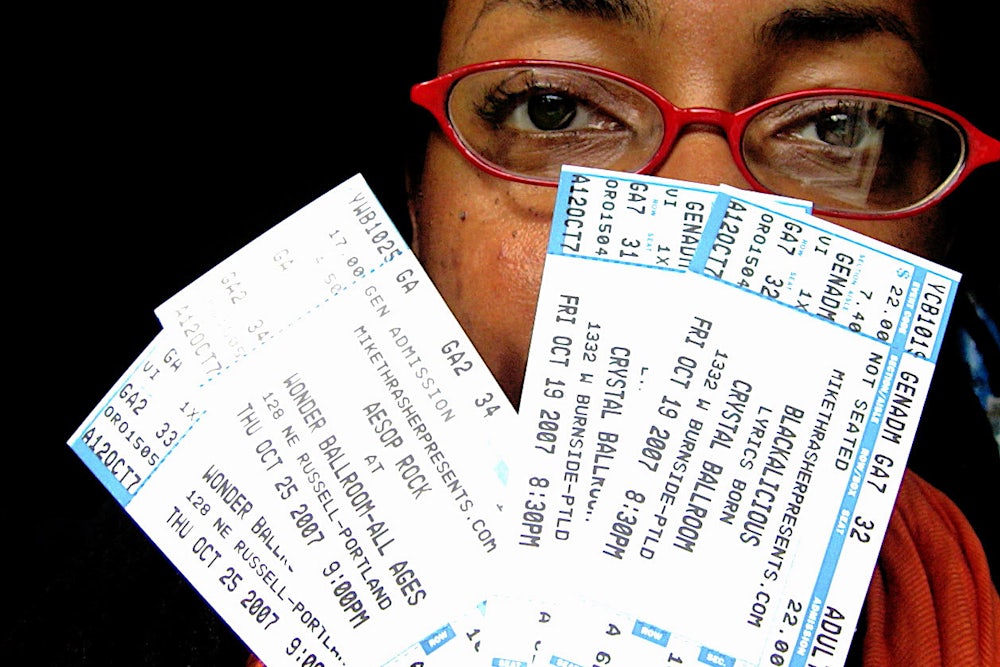

When I write about monopoly power, one popular complaint is that the issue feels too remote and abstract. Antitrust law is bound up in confusing terminology and complex measurements like the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index. But I reject the notion that people have no personal experience of how monopolies affect their daily lives. Have you ever bought a concert ticket?

If so, then you know the feeling. You waited weeks for tickets to become available, only for them to sell out in minutes—and then appear shortly thereafter on reseller websites, at a huge markup. Or you managed to get the tickets into your shopping cart, only to discover while checking out that there’s a hefty “processing fee.”

These are functions of monopoly. As a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report released on Monday shows, one company dominates the primary market for ticket sales and another dominates the secondary market. The failure to stop them from getting bigger and more dominant will only compound the problem.

Live Nation is by far the largest ticket provider in America, thanks in part to President Barack Obama’s Justice Department, which approved the company’s merger with Ticketmaster in 2010. Ticketmaster controlled over 80 percent of the market before the merger, and that holds true of Live Nation today, buttressed by its role as the nation’s largest concert promoter and owner of over 200 venues. Because Live Nation manages over 500 major music artists, they can demand that venues wanting to host concerts exclusively use Ticketmaster instead of a competitor.

The Obama administration’s settlement with Live Nation was supposed to prevent this. “There will be enough air and sunlight in this space for strong competitors to take root, grow and thrive,” said Christine Varney, then head of the Justice Department’s antitrust division. Remedies included Ticketmaster licensing its ticketing software to competitors, and selling off a subsidiary called Paciola. But the software quickly became obsolete, and Paciola remained a minor niche rival. Meanwhile, the combination of ticketing, artist management, venues, and promotion proved too much for anyone to compete. And that enables the ticket racket.

Nearly all tickets for concerts, theater performances, festivals, sporting events, and other forms of entertainment are sold online. Some are delivered through pre-sales for frequent buyers, fan club members or certain credit card holders, while others are sold on the release date. But they all come with service fees, processing fees, facility fees and the like. If you want the ticket delivered to you, there’s another fee for that. Overall, the average event ticket fee on a primary sale is 27 percent of face value, according to GAO. Financial disclosures indicate that nearly half of Live Nation’s revenue comes from those fees.

Typically, the buyer never sees these fees listed until right before they purchase the ticket, in a smaller font size than the face value of the seat. By now everybody expects fees attached to their tickets, and because there’s barely any competition among ticket distributors, there’s no option for a low- or no-fee business model.

There is, however, a secondary market, controlled mostly by StubHub, which claims 50 percent of the market for ticket resales. Ticketmaster is the number two secondary market seller, through an exchange called TicketsNow.com. Ticketmaster has settled cases with the Federal Trade Commission over steering customers to tickets above face value on TicketsNow without disclosure. Other “white-label” resellers make it look to consumers that they’re buying from the original venue, when they’re actually buying marked-up seats.

More typically, resellers acquire tickets by beating individual concert-goers to the punch, through superior manpower and bot software. Sometimes bots merely reserve a seat without buying it, making it look to a prospective buyer that the seats are sold. Then, re-sellers capitalize on the desperation of entertainment-seekers locked out of the original sale by substantially marking up the price. Fees remain in place as well; in fact, GAO found that fees on resale sites were 31 percent of the (often inflated) face value, a higher percentage than for primary ticket sales.

These problems are obvious to anyone who’s tried to buy a ticket, and they’re well-known to the government. The Justice Department said during the Ticketmaster/Live Nation merger that Ticketmaster’s dominance of event sales enabled high fees. The 2016 BOTS (Better Online Ticket Sales) Act was supposed to restrict bots from purchasing tickets for resale and allow the FTC to fine violators. But the BOTS Act has yet to lead to a single federal enforcement action.

This shafting of consumers fed one of the largest CEO pay packages recorded thus far in 2017. Michael Rapini, CEO of Live Nation, made $70.6 million last year, including $58.6 million in stock. The average employee at Live Nation makes $24,406, for a CEO/worker ratio of 2,893:1. Put another way, it takes just 41 minutes for Michael Rapini to earn the average worker’s annual wage.

Live Nation has made record profits for seven straight years. StubHub, a subsidiary of eBay, is similarly thriving from its dominance of the secondary market. Meanwhile, people wanting a little entertainment are getting screwed. “Coveted ticketed events are more expensive, harder to obtain, and larded with hidden fees as fans are being by squeezed for every nickel,” said Congressman Bill Pascrell (D-NJ), who had requested the GAO investigation. “Congress must step in to impose true oversight on an industry that makes its way ripping off customers.”

The report lists some possible remedies: making tickets nontransferable, to essentially kill the secondary market; capping prices on resales; and improving the disclosure of fees. But these can be difficult to enforce, and in the case of nontransferable tickets, incredibly inconvenient. The FTC already has tools to enforce deceptive practices by ticket sellers. Its new commissioner, Rohit Chopra, wrote in a memorandum on Monday that repeat corporate offenders should get hit with more serious penalties. But to date, enforcement has been lacking.

The heart of this problem is a concentrated market where there are no consequences for bad, expensive service. If the only way to see Taylor Swift or Jay-Z goes through Live Nation/Ticketmaster or eBay/StubHub, the companies have tremendous power to gouge fans.

What can the government do about it? The Justice Department is already looking into whether Live Nation engaged in anti-competitive practices by allegedly pressuring concert venues to use Ticketmaster. But the clearest solution is for the government to reverse its position: to effectively undo the merger, breaking the companies apart again. Promotion, ticketing, and artist management should be separate. Furthermore, no single company should be allowed to control 80 percent of the ticket sales market. That ought to be broken up as well, enabling competition on price and quality. You could do the same for the secondary market by limiting the number of event tickets for sale at any one exchange.

In other words, the bullying and deception at the heart of this industry would end if the market were structured to benefit ticket buyers, not giant companies.