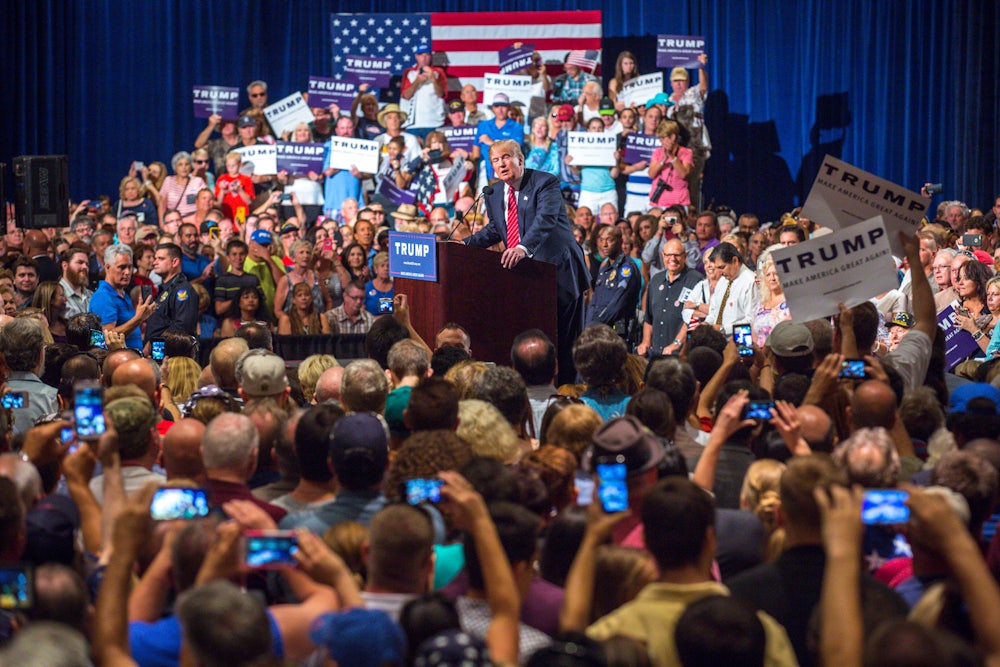

In a bid to offset the flurry of books critical of his presidency, Donald Trump has started something of a conservative book club, endorsing new releases that offer a rosier picture of his campaign and young presidency. One of those is The Great Revolt, by Salena Zito and Brad Todd:

“The Great Revolt” by Salena Zito and Brad Todd does much to tell the story of our great Election victory. The Forgotten Men & Women are forgotten no longer!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 7, 2018

It’s vintage Trump. The self-aggrandizement, the populist tone, the erroneous capitalizations—they are familiar tics, which appeal to his base and no one else. The question of Trump’s appeal ostensibly forms the backbone of Zito and Todd’s book. Zito, a reporter who writes for The New York Post and The Washington Examiner, and Todd, a Republican strategist, argue that Trump is an authentically populist figure: a chaotic but remarkable leader who transcended ideology to permanently alter American politics.* This version of Trump’s story—one where racism barely merits a mention—is glaringly incomplete, but it is useful in showing what Trump’s supporters tell themselves and how the left can respond.

The flaws of The Great Revolt are almost immediately obvious. “Trump’s nationalist argument was economically pragmatic from the start, devoid of the ideological language of the trench warfare that had stalemated presidential politics for the last 35 years,” Zito and Todd write early in the book. In truth, Trump’s nationalism was overtly driven by a certain ideology, best exemplified by his proposal to build a wall on the border with Mexico that would keep out “rapists” and “thieves.” The authors refer, later, to Trump’s “ideological apostasy,” his rejection of politics, and his anti-establishment appeal. When they do cover Trump’s racist remarks, they couch his rhetoric in euphemisms: His language is simply “nonpolitical, often coarse.”

The idea that Trump possessed no politics, that his campaign promoted no ideology, is a useful bit of propaganda that places his appeal outside anything so crass as pure bigotry. This is an unfortunate failure for numerous reasons, chief among them the fact that Zito and Todd had the resources to write a different book. The authors boast that they travelled “27,000 miles of backroads” to visit counties in the Great Lakes region, which is an expensive feat. Their so-called Great Revolt survey, which purportedly adds empirical backing to the book’s political conclusions, probably wasn’t cheap to administer either.

They had opportunity, too: Readers could benefit from a granular examination of Obama-Trump counties, those in which voters switched their vote from Obama in 2008 to Trump in 2016. The authors say Rust Belt counties are places “where most of America’s decision makers and opinion leaders have never been.” In this they have a point, if by “opinion leaders” they are referring to the press. A veritable genre emerged in the wake of Trump’s victory—the Trump Country Safari—in which journalists parachuted into the Rust Belt and Appalachia to try to explain Trump voters to the rest of America. But by focusing so heavily on bitter diner patrons, the press whitewashed what are in fact diverse areas of the country, while reinforcing the notion that economically anxious whites drove the Trump train to victory.

As it happens, this is the same flawed story Zito and Todd tell. But for Trump to be an economic populist, his policies should reflect some demonstrable interest in improving the lives of working people. His commitment to working people has always been in doubt (did anyone really expect more from a rapacious real estate mogul who hid his taxes and pledged to repeal Obamacare?), and this has only been affirmed by his policies since taking office, which have been bog-standard Republicanism. What Trump excelled in was expressing pure racial-cultural resentment, which makes him a certain breed of populist, but not an economic one. (In fact, the average Trump voter was squarely middle class.) Trump’s “revolt” was not subversive or revolutionary. After all, there’s nothing revolutionary about power re-asserting itself.

Without this necessary racial context, portraits of Trump voters become glamour shots. If Zito ever asks her sources pointed questions about Trump’s racism or misogyny, it’s not evident from the text. Instead, her subjects pontificate at length, seemingly without challenge or direction, and missed opportunities mount as the book progresses. Many hail from families that produced generations of union members, but they voted for Trump despite official union support for Clinton. Is this because right-to-work laws weakened unions? Did union leadership miscalculate by endorsing Clinton over Bernie Sanders during the Democratic primary? Or is it something else entirely?

These are questions Todd and Zito do not explore. They de-racialize support for Trump throughout their book: There’s an entire chapter on Trump-voting Christians, and not once do they mention that religious support for Trump falls cleanly on racial lines. Not only do these failures undermine the potential usefulness of the book’s Great Revolt survey, they fatally undermine the authors’ conclusions.

Zito and Todd claim that there are seven archetypes among Trump voters who once supported the Democratic Party. But these gradations are fuzzy, and they never quite map onto what voters actually have to say. In the end, Trump voters are mostly white, middle class, and Christian. They miss America’s “fighting spirit,” and disdain its cultural “weakness.” They think that the Democratic Party is aloof and that union leadership is corrupt. They either excuse Trump’s racism and misogyny, or they ignore it because it doesn’t bother them all that much. They are critical of a system that extracted labor and wealth from their communities, only to look for cheaper wage-labor overseas. And they all believe they’ve been left behind—forgotten, to use Trump’s term. There’s truth here, but it’s legible only when viewed through a lens that Zito and Todd reject.

In her 1989 book Fear of Falling, Barbara Ehrenreich argued that at the dawn of the 1960s the American middle class believed it had become universal. But poverty, of course, had not actually disappeared from America, and the work of social critics like Michael Harrington forced it back into public consciousness, where it was absorbed into a particular narrative. America was too abundant, too successful, for existing poverty to be proof of any structural failing. If people were poor, it could be attributed to choices they made.

That narrative has been challenged many times since, most recently in the aftermath of the Great Recession. This time it was much more difficult to pretend that structure had nothing to do with it. The U.S. government, including the Democratic Party, did betray Rust Belt voters, but not for the reasons Zito and Todd suggest. “In the short span of a generation, the face and focus of the Democratic Party nationally has shifted from a glorification of the working-class ethos to multiculturalist militancy pushed by the Far Left of the party,” they argue.

Considered against the Obama presidency in particular, the racial dimensions of their argument become clear: The Democratic Party got too black and brown, and abandoned white voters. It’s a familiar Trumpian dog whistle. As the party of minority rights, the Democrats have to accept they will lose some white voters. But they don’t need to lose these voters because they’ve fostered the perception that the party has gotten too rich—that it has become complicit in systemic inequalities. Still, the GOP has aligned itself completely with monied interests, and Trump embodies those interests.

So why vote for Trump over any Democrat? It comes back to resentment. When voters feel precarious, they become susceptible to demagoguery. So Trump invents the bad hombre, just as the GOP once invented the welfare queen. It’s a con job, and it works partly because the middle class does have cause for resentment. Something does block its upward trajectory. But poor immigrants aren’t blocking anyone’s path; that credit belongs to the wealthy, like Donald Trump and his cabinet.

Trump’s attraction lies both in his affect and in his wealth. His unvarnished rhetoric manufactures a sense of honesty, though he might be the most blatantly dishonest president this country has ever had. His prejudice may be the only honest thing about him. The American middle class, in a sense, purchased Trump. They purchased Trump for the same reason all consumers make an aspirational purchase. They hoped to buy his lifestyle, which reflects both their fear and their entitlement.

A strange, parallel blindness pervades The Great Revolt. Just as Trump voters misunderstand the roots, if not the reality, of their problems, so do Zito and Todd. The problem isn’t culture, it’s wealth—how it buys power and bleeds life from democracies. Zito and Todd can’t name the problem, and they certainly can’t name the solution. The left can.

*The original version of this article said Zito “previously” wrote for The New York Post and The Washington Examiner. She still writes for those publications. We regret the error.