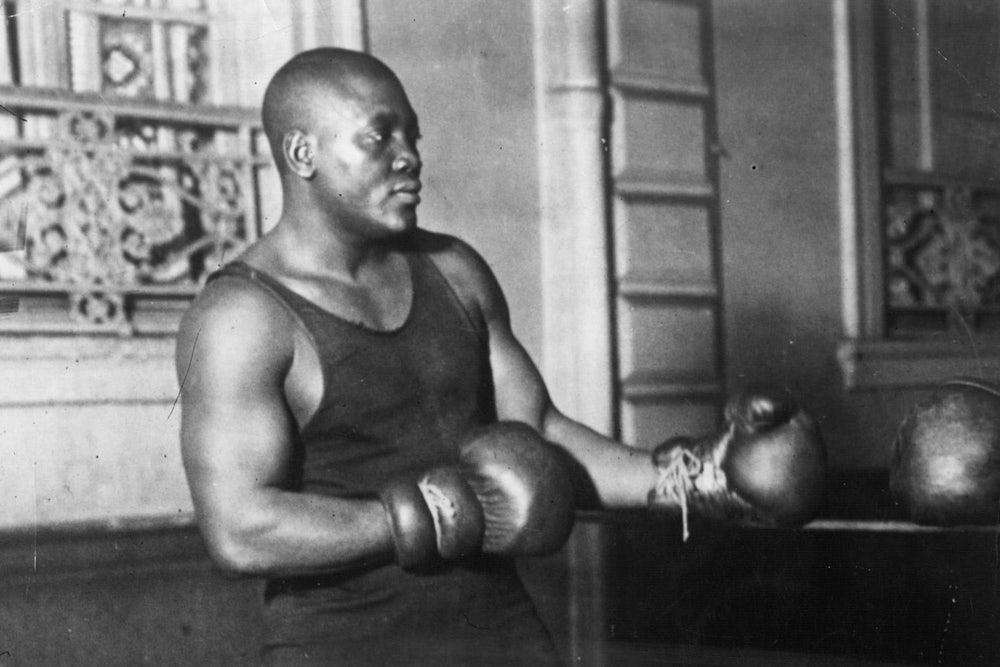

Johnson, who became the first black world heavyweight boxing champion in 1908, was a prime example of how sports are intertwined with racism in the U.S. His victory came as a shock to white Americans. Cynical promoters exploited the backlash by casting a series of challengers as “the Great White Hope.” Johnson’s matches became arenas of racial combat, often leading to outside-the-ring violence when white boxing fans rioted after his victories.

In 1912, Johnson was convicted of violating the Mann Act because he had dated a white woman; he fled to Europe and lived in exile for years before returning to the U.S. in 1920 to serve his sentence. On Thursday, President Donald Trump pardoned him. The New York Times reports:

The president called Johnson “a truly great fighter, had a tough life,” but served 10 months in federal prison “for what many view as a racially-motivated injustice.” Mr. Trump said the conviction took place during a “period of tremendous racial tension in the United States.”

The push for Johnson’s pardon had been going on for many decades. President Barack Obama resisted on procedural grounds—posthumous pardons are rare, and this one had not been cleared by the Department of Justice—but also because Johnson was accused of physical assaulting women.

Merits aside, Trump’s pardon of Jackson is curious given that the president is a cultural heir of those who exploited Johnson. In 2005, Trump proposed to NBC a season of The Apprentice pitting a white team against a black one. “It would be nine blacks against nine whites,” Trump explained in an interview. As a politician, Trump has continued the American tradition of attacking black athletes to stoke racial conflict. On Wednesday, he said of NFL players who don’t stand for the national anthem, “Maybe you shouldn’t be in the country.”